Ninth law of worker entropy: Difference between revisions

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) Created page with "The anal paradox is a theory of negotiation. It proposes that as the number of people involved in negotiating a contract increases the contract’s brevity, and comprehensibil..." |

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| (36 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

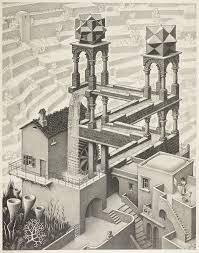

{{a|work|{{image|Waterfall|jpg|A [[security waterfall]] yesterday.}} | |||

}}Once known as the “[[anal paradox]]”, [[Otto Büchstein]]’s theory of [[negotiation]] has since become recognised as the [[JC]]’s [[ninth law of worker entropy]] — numerically challenging since, by some distance, it predates the [[Laws of worker entropy|first eight]], and indeed forms the basis for one or two of them. The month law of worker entropy explains why the [[tedium quotient]] of any legal agreement tends to infinity. | |||

{{ninth law of worker entropy}} | |||

Briefly stated, the paradox is this: however anal it may be to “[[Adding value|add value]]” through qualifications, clarifications, [[for the avoidance of doubt]]s, [[without limitation]]s and other forensic {{f|celery}}, once these “correctives” have been made it is even ''more'' anal to remove them again, seeing as, [[Q.E.D.]], they make no difference to the legal or economic [[substance]] of the agreement either way. So, inevitably, one won’t [[I’m not going to die in a ditch about it|die in a ditch about it]], however appealing by comparison that experience might, to a [[prose stylist]], seem, and the agreement will silt up to the point where its original intent is hard or impossible to make out. | |||

{{ | Hiring a dredger is expensive, and since the operating assumption of all [[Mediocre lawyer|lawyers]] is that {{maxim|no-one ever got sued for writing an unintelligible agreement}},<ref>“[[What the eye don’t see the chef gets away with|What the eye don’t understand, the chef gets away with]]”.</ref> you leave it (perhaps tossing in a [[disclaimer]] for good measure) until one day your [[contract]] nears the [[event horizon]] of intelligibility, beyond which it risks collapsing in on itself, by which the idea is that you will be well clear, having moved on to some other unsuspecting host. If you have not there is the risk of it taking you with it, and precipitating the [[boredom heat death]] of the universe. | ||

It almost happened in [[2008 ISDA Master Agreement|2008]], so don’t joke about it. | |||

{{sa}} | |||

*[[Laws of worker entropy]] | |||

*[[Adding value]] | |||

*[[Schwarzschild radius]] | |||

{{c2|Cosmology|Astrophysics}} {{c|Paradox}} | |||

{{ref}} | |||

{{c|tedium}} | |||

{{C|Laws of worker entropy}} | |||

Latest revision as of 13:30, 14 August 2024

|

Office anthropology™

|

Once known as the “anal paradox”, Otto Büchstein’s theory of negotiation has since become recognised as the JC’s ninth law of worker entropy — numerically challenging since, by some distance, it predates the first eight, and indeed forms the basis for one or two of them. The month law of worker entropy explains why the tedium quotient of any legal agreement tends to infinity.

The JC’s ninth law of worker entropy: As the number of people involved in negotiating a contract goes up, its brevity, comprehensibility and utility goes down. The longer a negotiation continues, the more compendious, and tedious, will be its“fruits” — the verbiage, in the vernacular — even as its meaningful commercial content stay constants (or, more likely, declines to vanishing point).

Briefly stated, the paradox is this: however anal it may be to “add value” through qualifications, clarifications, for the avoidance of doubts, without limitations and other forensic celery, once these “correctives” have been made it is even more anal to remove them again, seeing as, Q.E.D., they make no difference to the legal or economic substance of the agreement either way. So, inevitably, one won’t die in a ditch about it, however appealing by comparison that experience might, to a prose stylist, seem, and the agreement will silt up to the point where its original intent is hard or impossible to make out.

Hiring a dredger is expensive, and since the operating assumption of all lawyers is that no-one ever got sued for writing an unintelligible agreement,[1] you leave it (perhaps tossing in a disclaimer for good measure) until one day your contract nears the event horizon of intelligibility, beyond which it risks collapsing in on itself, by which the idea is that you will be well clear, having moved on to some other unsuspecting host. If you have not there is the risk of it taking you with it, and precipitating the boredom heat death of the universe.

It almost happened in 2008, so don’t joke about it.