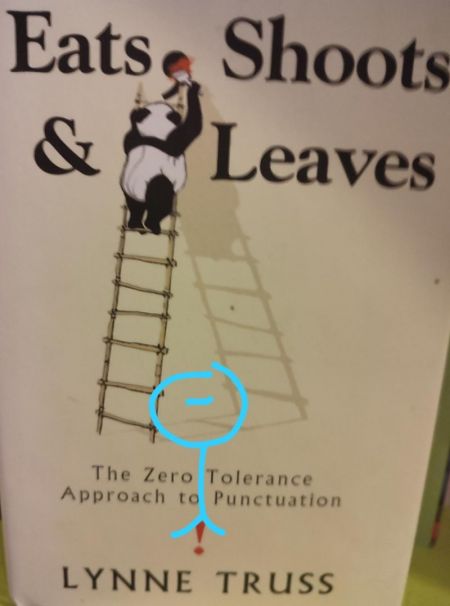

Eats, Roots and Leaves: The Zero Tolerance Approach to Punctuation

|

|

What do you say about a zero-tolerance approach to punctuation that mis-punctuates its own title?

It is a good thing that a book on punctuation is a best-seller; it’s just a pity it’s this one.

All the good work Lynne Truss does in conveying her message (viz., punctuation matters) is undone by her hectoring tone, lacklustre attempts at humour (not helped by a habit of pointing out punch-lines) and, in the final analysis, lack of credibility: having set out rules she then reverses over them, makes egregious appeals to authority and, every now and then, just gets things flat out wrong.

You might forgive that were there any humility in her prose, but there isn’t. The first rule of hubris is: if you’re going to be a smartarse, make sure you’re right, because readers won’t cut you any slack if you’re not.

Lynne Truss isn’t always right.

A case in point: in her introduction, Truss states on behalf of fellow sticklers, “we got very worked up after 9/11 not because of Osama bin-Laden but because people on the radio kept saying “enormity” when they meant “magnitude”, and we hate that”.

Even leaving aside the tin ear, she is quite wrong to take umbrage here: “enormity”, in British English, means “extreme wickedness”. The magnitude and the awfulness of an act of mass murder are related. So, even in British English, it is perfectly right to talk of the “enormity” of September 11. But if any of the voices Truss heard on the radio were American, they had another excuse. In American English enormity does mean “magnitude”. Since Truss is so enamoured with appeals to authority, it is odd she didn’t check that with the best authority on American English, Webster’s dictionary.

When she does make them, Truss’s appeals to authority are even more irritating, particularly where they contradict her own rules or justify her own errors: So, the author patiently explains that an apostrophe is required to indicate possession except in the case of a possessive pronoun (i.e., “mine”, “yours”, “his”, “hers”, “its”, “ours” and “theirs”). Now, I had always wondered why a possessive “its” doesn’t have an apostrophe, and this explains it nicely. But then Truss completely undermines her own rule and appeals to the authority of Virginia Woolf:

“Someone wrote to say that my use of “one’s” was wrong (“a common error”), and that it should be “ones”. This is such rubbish that I refuse to argue about it. Go and tell Virginia Woolf it should be “A Room of Ones Own” and see how far you get.”

Virginia Woolf’s been dead for seventy years, so this is tough to do. But it doesn’t mean Virginia Woolf was right. And Truss fails explain why this is “such rubbish”.[1]

Finally, the book’s title: I don’t think she gets the joke. It has nothing to do with waiters or pistols (perhaps a maiden aunt told her that one?) and certainly doesn’t need a “badly punctuated wildlife manual” to work, because it isn’t a grammatical play; it’s an oral one. The joke doesn’t work when you write it down, precisely because of that ambiguous comma. You have to say it out loud (in spoken English, there is no punctuation at all).

They missed the chance to re-title the New Zealand edition of this book, because the local version of the joke (which employs a delightful expression from NZ English) is funnier: The Kiwi, it is said, is the most anti-social bird in the bush, and no-one likes to invite it to parties, because, if it turns up at all, it just eats roots and leaves.

The joke’s about shagging.

See also

References

- ↑ Many years after posting this review, I was put out of my misery by a correspondent who kindly explained why "one's" should indeed take an apostrophe: "It is only personal possessive pronouns (mine, his, her, our, etc) that do not take apostrophes. "One" is an indefinite pronoun, so using it in the possessive sense ... it takes an apostrophe, and hence why we ought not torture Ms Woolf in her grave."