Inconsistency

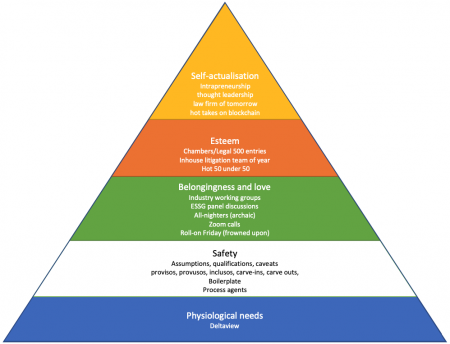

Abraham Maslow proposed a “hierarchy of human needs” in his famous 1943 paper A Theory of Human Motivation.

|

Towards more picturesque speech™

A legal eagle’s hierarchy of needs, yesterday

|

Legal eagles have their own hierarchy of needs, as indeed do the legal confections they create. This wiki is devoted to them: you might subtitle it “A Theory of Legal Eagle Motivation”.

Somewhere near the other top of the eagle’s list — nest? — is the need for utter, nose-bleeding clarity in legal expression. To be sure, wizened malcontents might advance the counter-hypothethesis that a little constructive doubt is no bad thing, but no-one really cares about them and, inevitably, the will to certainty prevails.

It finds its apotheosis in the “inconsistency” clause which addresses what should happen where two intesecting contracts conflict.

One might — alack; one fruitlessly does — retort that a skilled draftsperson should not create conflicting contracts in the first place. Quite so: but the architecture of legal documentation in the financial markets is such that conflicts are not just inevitable, but intended: the schedule to the ISDA Master Agreement is designed to override contrary provisions in the pre-printed boilerplate ,where the parties so agree. Of course, there it goes without saying that a purpose-built overriding schedule should, as intended, override.

But nowhere is it written in the legal practice manual that a proposition’s going without saying is necessary or sufficient grounds for it not being said. Why not say it, for the avoidance of doubt? What harm does it do?

One might — aye; fruitlessly does — reply that a skilled draft person should draft without doubt in the first place. But here we are.