Signs

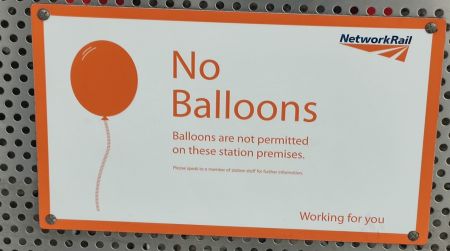

The JC doesn’t like the sorts of signs that warn you, or forbid you, or tell you what you can or cannot do. They emanate from the same passive aggressive instinct as the email sent from an unmonitored account — they’re a cheap shot at someone who can’t hit back — and more to the point they are a failure in design: if you don’t people to walk on your grass, stick up a fence, or pave the damn thing, or create some obstacle — do with life code what you are trying to do with bossiness.

|

The design of organisations and products

|

So some thoughts about notices, which we will arbitrarily define as written directions to do, or refrain from doing, something.

If in doubt, use design principles to avoid signs

Most signs — other those amounting to labels or imparting directions — don’t work very well. They imply a failure in the design of a built environment: a well-designed environment no more needs warnings and instructions, than does a well-designed kettle.

The language of design: affordances, signifiers, mapping and feedback — Don Norman’s The Design of Everyday Things can tell you what you need to know about these — can help, but your goal should be psychological. If you have designed your space well, then — with the exception of signposts — it shouldn’t need signs. If the desire lines run contrary to the design principles of your built environment such that you need signs warning you off the grass, you have got your design wrong. This is not the punters’ problem: it is yours. Their desire lines point the way to your mistake.

If you really can’t have people walking on your grass, build a fence. But if you want an unfenced lawn and you expect people to walk around it, ask yourself why. Use a hardier grass seed.

But if you are just being an officious twerp because it is your property and you can, well — don’t.

Where signs are okay

Some signs we won’t mind. They’re part of the design: they impart vital information where there’s no better way of transmitting it. Signs that help you figure out what you want, and it can’t otherwise be made obvious through design and affordance. Maps, menus and street signs, for example: There’s only one way of being sure I’m on Oxford Street, and that’s by erecting a sign saying “Oxford Street”. This is a label, not a notice. You are free to ignore it at will.

Likewise, it is good to know that this is the turn-off for Stansted: the M11 is a long motorway and it has lots of exits, and there’s no easier way of intuitively knowing. Incidentally, the design of Britain’s road signs by Margaret Calvert and Jock Kinneir is a minor triumph of modern design.[1]

And a menu: well how am I supposed to know what’s on your menu without, well, a menu? But here be brief, clear — monosyllabic.

Likewise, where a condition is temporary enough that a redesign of the space is not practicable: So: “closed for maintenance”, or “thank-you for wearing a mask and maintaining social distancing”.

See also

References

- ↑ read more here. And here.