Vitamins and painkillers

The theory goes, so say any number of thought-pieces, that there are two kinds of business offerings: painkillers — that address acute immediate problems, and vitamins — that invisibly guard against problems over the medium to long term.

|

Crappy advice you find on LinkedIn™

|

One that won’t make me nervous

Wondering what to do

One that makes me feel like I feel

When I’m with you

When I’m alone with you

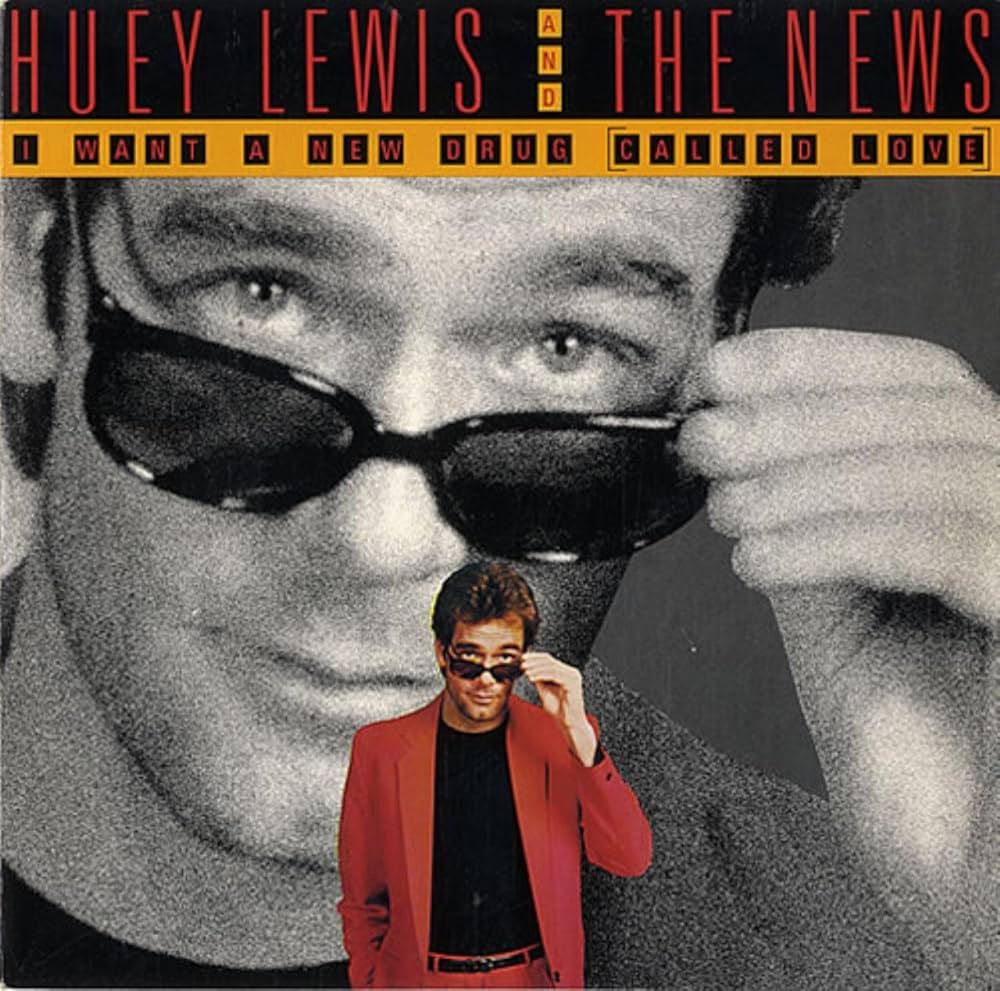

- — Huey Lewis, I Want A New Drug (1984)

Opinion is divided as to which is better: painkillers yield quick revenues in the short term but have low barriers to entry and are, thereby on-piste; vitamins generate returns more slowly but are stickier, build better relationships, and might be a more stable source of income over the longer term.

Seeing legal service as something that either masks a deep-seated malaise without fixing it — a “painkiller” — or that is a quick, cheap and hard-to-prove substitute for the boring work of living a healthy lifestyle — a “vitamin” — but anyway overlooking, you know, diagnosing and curing patients is the classic legal-tech take.

But let us extend what may be just a bad metaphor.

Painkillers

Long-term or frequent use of pain medications can lead to gastrointestinal problems and kidney damage, and the medication may become less effective over time. Additionally, some painkillers may interact adversely with other medications.

- — ChatGPT, proving it can speak more sense than management consultants

Thus the appeal of Paracetamol: it is quick, generic, asks no great skill of those who prescribe it and, at first blush, it does the trick. A lot like legaltech.

Painkillers work in three cases: where problems are superficial, baffling or terminal.

Patients with superficial or terminal conditions may be grateful but they won’t pay much — at least, not for long.

Where a patient’s condition baffles. either it is a freak, or you are a bozo.

Freaks are — freaks, right? The exception. That leaves lots of bozos.

And here is the JC’s main gripe with the legal operations world: much of it presumes that you can solve deep-seated, difficult problems, with generic technology and cheap, low-skill labour.

If this were true, law would not be such a persistently lucrative profession. Everyone would have done this by now.

Now the cynical view — one, by the way, the JC largely shares — is that most sticky legal problems aren’t all that difficult, being premised not on solving real-world problems, but feathering legal nests. Lawyers tell ghost stories and then charge their clients to plan ornate escape routes should these phantasmagoric contingencies come about.

If this is the problem to be fixed, then “optimising for absurd outcomes” — in other words, leaving the fantasies and complications in place, but muting the pain so customers don’t notice — is no great answer. Any bozo can do that.

What the customer needs is someone — or something— to debunk the ghost stories, demythologise sacred scripts, untangle knotted organisations, sort wheat from chaff and give simple, clear, practical advice.

The customer needs BS defeat devices that keep feather-bedding legal eagles out of the picture.

Not any bozo can do this. Diagnosing this sort of thing, at the best of times, is hard. And, when the patient institution was forged through countless regrettable mergers, siloed, outsourced, downsized, recombined, spun out, reverse-merged; when it is sclerotic, riven by turf wars, wracked with ancient enmities, haunted by a catastrophic past; when it is bound, encrusted and silted up with generations of bad practice, lazy governance, mis-engineered process and perfidious policy — when the patient presents with a persistent consumptive, hacking wheeze — treating it is even harder.

Vitamins

Most people do not need to take vitamin supplements and can get all the vitamins and minerals they need by eating a healthy, balanced diet.

Painkillers, at least, make a quick, demonstrable difference. Vitamins are more oblique in their quackery: their instant appeal is to sound technical. Since, by design, vitamins aren’t meant to work immediately, patients are usually not disappointed when they don’t.

Matter-management technology is the vitamin du jour, especially inhouse. It pitches well — GCs love it — but however fine it is in principle, its actuality is forlorn.

The most remunerative course of vitamins is one that never ends, of course. If it doesn’t kill the customer outright, it must stay the course in perpetuity, its benefit eternally deferred.

This permanently delayed gratification offers great scope for intervening causes. By the time the vitamin “effects” are meant to kick in, who knows? The patient could have mended its dissolute ways by itself, in which case you can take the credit. Me and my magic vitamins!

More likely, of course, the patient will be sicker than ever. Even if you haven’t seized the chance to scarper, time allows alternative causal explanations to intrude. Geopolitical events — COVID, Brexit, Ukraine, climate change and so on — are easy to cite and magnificently unfalsifiable.

The real business of restoring a patient’s vitality is, again, much more work and much less glamour. However much prudent counsel might recommend this, it doesn’t pitch well. No-one wants to be told to lay off the booze, cut out the fags, go jogging and eat more vegetables.

So what do we recommend instead? Aspirin and vitamins!