Give up

Never surrender. A give up is, in practical theory, an arrangement whereby a hedge fund “gives up” pending transaction — be it a derivative or a cash trade — it has executed (or, cough, unsubtly hinted it is “highly interested” in executing) to its prime broker, who accepts the hedge fund’s contract with the executing broker on condition that it puts on an economically identical off-setting transaction with the hedge fund.

|

Brokerage Anatomy™

|

It sounds, you might think, like some kind of novation. But oh, no. That would be far too sensible.

There are three normal ways of giving up, and ironically none of them involve a contract which is “given up” as such. To make matters worse, the three methods are profoundly different in every respect.

ISDA give-ups

ISDA give-ups only work if what you are purporting to give up is itself an ISDA Transaction — an not a hedge to an ISDA Transaction (unless it is, itself, an ISDA Transaction). ISDA give-ups are therefore most frequently spotted in credit derivatives, interest rates and cross currency swaps. Equity derivatives, on the other hand, tend to be hedged by physical assets (i.e., shares), so you wouldn’t use an ISDA give-up to settle a synthetic equity trade, for example.

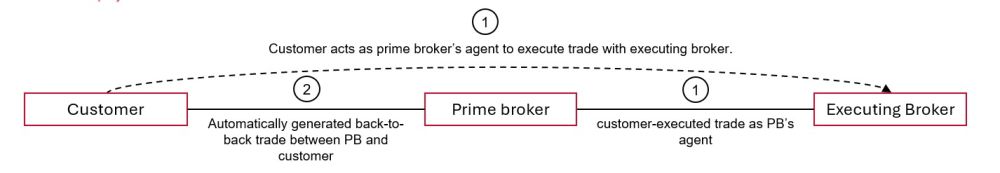

Under the 2005 ISDA Master Give-Up Agreement, a fund may “give up” derivatives it has traded with a broker to its Prime broker. It will usually do this because it does not have an ISDA Master Agreement with the broker. Under this arrangement the hedge fund acts at all times as the prime broker’s agent (it may not be a client of the executing broker at all) and never creates its own principal contract with the executing broker, but simply arranges the contract between the executing broker and the prime broker. The PB then puts on a back-to-back trade with the HF under the ISDA Master Agreement between them. Net result: the PB intermediates between EB and HF. Calling this arrangement a “give-up” is something of a misnomer.

Equity swap give-ups

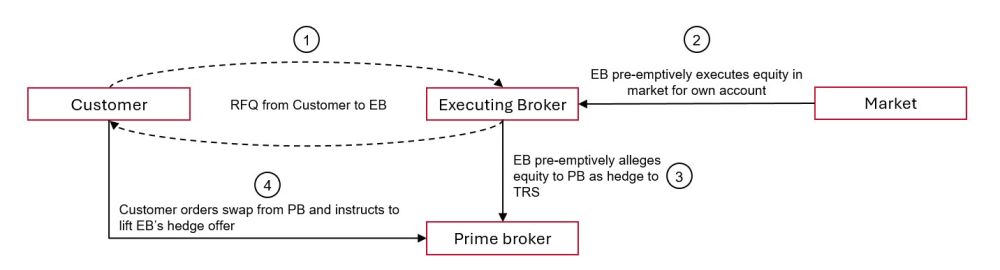

When a hedge fund wishes to obtain synthetic equity exposure to a Share from its prime broker, it may sometimes source the hedge for that swap from a different executing broker who will “give up” the order as follows:

- HF seeks a firm quotation for a Share (i.e. the underlier of the desired Equity Swap, not the swap itself) from the EB (tacitly on the basis any resulting trade will be given up to a known PB). At this stage, there is no actual order: all is .

- EB makes price discovery by actually executing a market trade in the Share for its own account (i.e., as a market-maker, not a broker per se) and communicates that price plus commission (P) to HF as a firm offer.

- HF says, “Thanks, EB. You will be hearing from my prime broker”.

- (Simultaneously)

- PB accepts EB’s cash equity allegation (where it breaches limits PB could DK the trade but usually would not: easier just take the trade, unwind it[2] and pass on any gain or loss to HF) and fills HF’s swap order at P.

- PB rehypothecates its Share hedge into the triparty system (via its own long box) against cash which it uses to reduce its borrowing from treasury.

Resulting position: EB is out of the picture, there is an synthetic equity swap between PB and HF, PB is hedged with a physical Share which it has financed in the triparty stock lending market. Easy.

Note: equity give-ups are the standard way of executing delta-one equity swaps in the European market, a common method in APAC, but unheard of in the U.S. This is mainly due to their varying attitudes towards tax.

Under a cash equity give-up, the hedge fund seeks a firm price indication for a cash equity from an executing broker, but does not act on it: rather, the hedge fund says, “all right, sir: hold that thought”, and runs off to its favourite prime broker, whom it instructs to enter into a swap at the exact price quoted by the executing broker, directing the PB’s attention to the winsome executing broker who is sitting by the phone, dutifully holding its thought, all dressed up and with nowhere yet to go.

In practice, the executing broker is not quite that demure. It will pre-emptively “allege” the cash trade to the hedge fund’s prime broker,[3] which is rather like buzzing in on University Challenge before Bamber Gascoigne has finished asking the question: “a little birdie tells me you are going to instruct me to trade on an equity to hedge an equity swap you’re about to put on with your client hedge fund X. Well — here it is!”

Once the PB has accepted the EB’s “allegation”, the PB “prints” the trade with the hedge fund, usually in the form of a synthetic equity swap[4] transacted under an ISDA Master Agreement.

Calling this a “give-up” is a misnomer, since nothing is actually “given up”. In theory — even if not awfully often[5] in practice — the prime broker can feign ignorance and refuse to transact with the executing broker, thereby hanging the executing broker out to dry with any recourse against anyone for the equity trade it has executed.

The executing broker may have stern words to the hedge fund about this, but not ones that would sound in actual damages (but — you know — good luck with your ongoing relationship with that broker, right?): the entire theory of their arrangement is that the hedge fund never committed to any trade with the executing broker. All care, no responsibility.

Why all this delicate tiptoeing around the subject? Tax, in a word. There are no[6] stamp duties payable on equity derivatives. There are all kinds payable on cash equity transactions.[7] So the name of the game is that the fund is arranging a transaction between two brokers, not executing one.

Regulated broker-dealers may have intermediary exemptions from these; clients like hedge funds generally will not. So if the taxman decides that the fund has bought the security from the executing broker and then sold it to its prime broker, then the hedge fund gets hit for stamp duty twice. If the broker buys directly from another broker, there will be at the most one dutiable transaction (and, if intermediary relief applies, there may be none).

Fixed income give-ups

NOTE: SOME OF THIS IS SPECULATIVE AND MAY YET BE WRONG.

Actually, that is true of this entire Wiki. But anyway, here’s a speculative description of a give up on a bond total return swap.

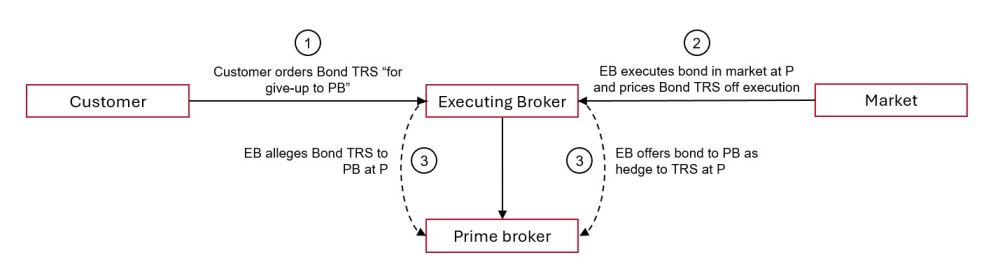

This (I think) would be the classic bond TRS give up flow:

- HF places order for a TRS with its EB (i.e., order for swap, not underlier, as in Equity PB) directing it to be given up to PB 2. EB executes a TRS with the HF as follows:

- Per HF’s instructions EB alleges the TRS and the bond hedge to PB at P.

- If within lines, limits etc., PB:

- Accepts the swap (by novation)

- Accepts the bond hedge (as a DVP trade with EB, against payment of P), funded from PB’s treasury.

- If not within the lines, PB could DK the swap and hedge, but more likely would just accept them, make the EB good on its two trades, and then immediately unwind its swap with HF and sell the bond, passing on any MTM loss or gain to HF.

- EB is now out of the trade.

- PB now repos the bond hedge out to the repo market, raising cash against the asset, and returns cash to PB’s treasury.

Differences from an equity TRS give up:

Customer trades a swap with the executing broker, not just a hedge

Firstly, the customer places an order for an actual TRS with the executing broker, rather than merely sourcing a hedge for a swap it will later enter with the prime broker, as it does in the equity swap market. Ask me why. Go on.

I don’t know for sure, but here are some hypothetical speculations: For one thing, cash bonds often have limited liquidity, whereas equities absolutely do not. There is only one common equity, ever, and it has very simple terms. Corporations issue lots of bonds of different shapes and sizes, they are weirdly priced because of coupon payments and contractual funnies, so it stands to reason a single equity instrument in one issuer will see more trading activity than will any given instrument in a diverse portfolio of bonds And consequently will be a great deal more liquid and its pricing more transparent.

For another, experts will tell you the TRS market itself has become quite liquid with standardised terms, though I struggle to see how a derivative of a financial instrument can somehow bootstrap itself into a position of more fungibility and liquidity than the underlying financial instrument itself. The other reasons I’ve heard don’t make a great deal of sense to thie bear of little brain so he won’t trouble you with them.

Customers actually trade with a FI executing broker

Secondly, the customer actually places an executable order with a fixed income executing broker for a real swap — meaning, technically, it is an executing dealer, but let’s park that — rather than merely seeking a firm quotation for a hedge as it does of executing brokers in the equity market. This is for tax reasons: equity transactions attract stamp duty in certain jurisdictions,[8] but equity derivatives do not. It is important for tax reasons not to be seen to be “controlling the prime broker’s hedge”, and buying it for the PB is exactly the sort of thing one should be at pains to avoid.

Bonds give the PB balance sheet problems. Equities don’t.

The vagaries of international financial reporting standards mean that bonds are significantly harder to keep off one’s balance sheet than are equities. The exact reason for this is difficult to fathom but seems to have something to do with bonds’ innate susceptibility to financial jiggery-pokery.

As mentioned, equities are uncomplicated, old fashioned instruments. They don’t have intricate legal terms as such: they just represent the net equity value of a portion of a commercial undertaking. Bonds, on the other hand, and ownership interests but claims. They have terms and conditions: issue dates, maturity dates, coupons, and may have all kinds of secondary features: convcersion options, calls, puts, knock-ins and knock-out events. They represent a performance risk to a specific contractual claim, rather than a simple ownership of a share in an undertaking.

Why that justifies different accounting is not immediately obvious. It does not have anything to do with the form of securities financing contract: economically, repos and stock loans are identical, the only difference being the collateral leg of a repo is usually cash, and in a stock loan is usually non-cash assets. The only thing I can think of is that a contract of indebtedness is a time-bound claim for performance against a company, whilst a share is a entitlement to the residual equity in an undertaking and is much more economically straightforward.

ETD give-ups

Documented under the FIA standard giveup documentation, available free to the world, here. There is a Customer Version and a Trade Version of the Electronic Give-Up System (EGUS).

The ETD give-up is the only one that functions as a real trade between client and executing broker and then a novation of that trade from client to clearing broker, at which point a back-to-back transaction springs into life between the clearing broker and the client.

See also

References

- ↑ This instruction to execute at X is so PB can accept the give-in while satisfying best execution requirements, which permit a broker to trade at an instructed price even though it isn’t the best one.

- ↑ By selling the Share at prevailing market: it is unlikely to have moved far unless the market is dislocated.

- ↑ Whose identity the hedge fund may have “inadvertently” let on during the post-coital conversation. WAIT: THERE WAS NO COITUS, REMEMBER?

- ↑ A.k.a a “contract for differences” or “CFD”.

- ↑ That is to say, ever.

- ↑ Okay — mostly no stamp duties. In the US, Section 871(m) has gone some way to equalising the tax payable under synthetic and cash transactions, which means the resting state of squeaky-bummitude of your US tax attorneys is now some way more comfortably positioned than it was in the old days.

- ↑ SDRT in the UK, FTT in various European jurisdictions, and in the US a typically baroque arrangement covered in Section 871(m) of the Internal Revenue Code.

- ↑ Notably the UK. It is much more harmonised now in the US after FATCA but there are, always, exceptions that keep things nice and complicated for your local tax advisers to clip their tickets.