Guide to the legal profession

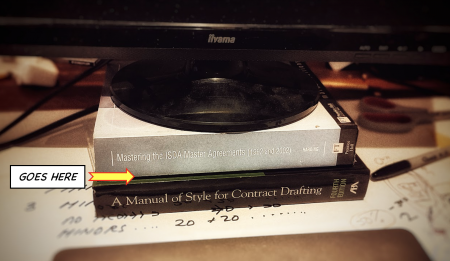

Those vanity-published[1] annual guides to the profession are invaluable to the modern practitioner: they are sturdy, stable, give a good inch or so of clearance each, and can be used in groups. Even competing products (like the “Legal 500” the Chambers Global Practice Guides or our old friend that FT book about derivatives) are stackable, interoperable, and backwards-compatible. All told, an excellent adjunct to any firm’s HSE policy, because it is supremely important that your monitor is at eye-level.

|

Office anthropology™

|

A legal almanac scores over the traditional ream of A4 printer paper in one key regard: durability. Because it has is no other practical use, you may stuff two or three of them under your screen without fear of having to disassemble your workstation later because you are in a rush and the last sod to use the printer didn’t restock the paper supply. A ream as a monitor prop, you see, is a private stash. A physical almanac is no more than prospective recycling.

Still, recent times have been tough for legal almanacs and their publishers, who have been hit by a triple cocktail of woe:

Critical theory got ... critical

In 2019, from nowhere, publishers were forced into bouts of panicked defensive virtue-signalling when their “rigorous selection methodology” for inclusion in these guides — largely “recommending your buddies as a prank and then voting for each other” — was found to be doctrinally wanting by humourless critical legal theorists.[2]

The response, though quite reasonable —“wait a minute? No-one reads these guides, do they? Doesn’t everyone just use them to prop up their monitors?” — fell on deaf, delicate ears.[3]

Covid goes virtual

But the trouble didn’t stop with a couple of beanish snowflakes. The Covid pandemic prompted legal almanac publishers to go digital, demonstrating exactly the same category error the critical theorists made, which was to assume that people want professional guides in order to read them.

But a moment’s reflection should tell us they do not: one looks up one’s own entry and, if it is there, sends a photocopy to mum; if not, commends yet another quiet resentment to the eternal pool in one’s interior monologue but then swiftly rallies and gathers oneself, by putting the guide to any of its many better uses: propping up monitors, holding open fire-stop doors, being dotted around the department between pot plants to make the place look learned, or just loafing around passively on filing cabinets. Legal guides can survive this way for years.

Now this being the case, an e-version of a legal almanac no good at all unless you print it out. But that would blow a ream of virgin printer paper, and you are better just to use the ream as it is, lest you later need it to cover a late-night printing emergency.

But it becomes less likely by the day that you you will. Covid is a double crisis for almanac publishers because the working mediocritariat has realised it doesn’t need to print, so no-one does any more, and there are oodles of reams lying around the office, which make perfect monitor stands...

See also

References

- ↑ TAKES ONE TO KNOW ONE, RIGHT?

- ↑ Or perhaps practitioners, posing as humourless critical legal theorists, who were disappointed not to have been included.

- ↑ But publishers are nothing if not resourceful, and they came out fighting, with yet more ways to arbitrarily divide up the city: the new “Chambers Diversity & Inclusion” guide, for example, catalogues the exclusive intersectionally-marginalised global elite (see: https://diversity.chambers.com/ “Diversity and inclusion is at the very heart of what we do and who we all are. We are, in that regard, all the same: we screen our people to make sure D&I is a fundamental part of their, and therefore our, DNA.”