Guide to the legal profession

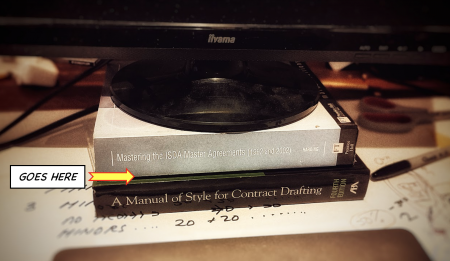

Those vanity-published[1] annual guides to the profession are invaluable to the modern practitioner: they are sturdy, stable, give a good inch or so of clearance each, and can be used in groups. Even competing products (like the Legal 500, the Chambers Global Practice Guides and our old friend that FT book about derivatives) are stackable, interoperable, and backwards-compatible. All told, an excellent adjunct to any firm’s HSE policy, because it is supremely important that your monitor is at eye-level.

|

Office anthropology™

|

Such a legal almanac scores over the traditional ream of A4 printer paper in one key regard: durability. Because it has is no other practical use, you may stuff two or three of them under your screen without fear of having to disassemble your workstation later because you are in a rush and the last sod to use the printer didn’t restock the paper supply. A ream as a monitor prop, you see, is a private stash. A physical almanac is no more than prospective recycling.

Still, recent times have been tough for legal almanacs and their publishers, who have been hit by a triple cocktail of woe:

Critical theory got ... critical

In 2019, from nowhere, publishers were forced into bouts of panicked defensive performative virtue-signalling when their “rigorous selection methodology” for inclusion in these guides — largely “recommending your buddies as a prank and then voting for each other” — was found to be doctrinally wanting by humourless critical legal theorists.[2]

The response, though reasonable — “wait a minute: no-one reads these guides, do they? Doesn’t everyone just use them, like we do, to prop up their monitors?” — fell on deaf, delicate ears.[3]

Covid goes virtual

But the trouble didn’t stop with a couple of beanish snowflakes.

The Covid pandemic prompted publishers to go digital, demonstrating exactly the same category error the critical theorists made: to assume that people want professional guides in order to read them.

But a moment’s reflection should tell us they do not: one looks up one’s own entry and, if it is there, sends a photocopy to mum and, if not, commends yet another quiet resentment to the eternal pool in one’s interior monologue, and then swiftly, bravely rallies, rising above it and gathering oneself. The best way to do this is to put the guide to one of its many better uses: propping up monitors, holding open fire-stop doors, dotting them around the department between pot plants to make the place look learned, or just loafing around passively on top of filing cabinets. Legal guides can survive this way for years.

Now this being the case, an e-version of a legal almanac is no good at all unless you print it out. But that would blow a ream of virgin printer paper, and you are better just to use the ream as it is, lest you later need it to cover a late-night printing emergency.

But it becomes less likely by the day that you you will need to do that. Covid has been a double bummer for almanac publishers, because since the working mediocritariat was forbidden from printing anything for eighteen months, it has largely now realised it doesn’t need to print anything and has got out of the habit, so even though we’re back in the office a day every week, no-one uses printers any more, and there are oodles of surplus reams of A4 lying around the office, which make perfect monitor stands...

Anonymous praise!

Most baffling, to almanac inductees, are the “anonymously-submitted” client lionisations, which — inductees being self-effacing folk, they purport not to recognise, but are profoundly, publicly, grateful for, all the same. LinkedIn is, as usual, the natural home for this type of humblebraggadocio. So:

Shameless self-promotion, but[4] thank you to the anonymous client who submitted feed back that “Basil is diligent, committed, pragmatic and always commercial, and shines golden beams of gravitas on everything to which he turns his attention. I cannot wait for his next novel”. I don’t know quite what to say!

I do: it involves a bucket. The great temptation is to call Basil’s bluff here. This is what LinkedIn’s comments facility was designed for. “That’s wonderful feedback, @Basil, and so richly deserved! Surely with the power of the network and the process of elimination, we must be able to identify that anonymous benefactor. I’ll start. It wasn’t me. Anyone else?”

See also

References

- ↑ TAKES ONE TO KNOW ONE, RIGHT?

- ↑ Or perhaps practitioners, posing as humourless critical legal theorists, who were disappointed not to have been included.

- ↑ But publishers are nothing if not resourceful, and they came out fighting, with yet more ways to arbitrarily divide up the city: the new “Chambers Diversity & Inclusion” guide, for example, catalogues the exclusive intersectionally-marginalised global elite (see: https://diversity.chambers.com/ “Diversity and inclusion is at the very heart of what we do and who we all are. We are, in that regard, all the same: we screen our people to make sure D&I is a fundamental part of their, and therefore our, DNA.”

- ↑ Yes, it is shameless, and admitting that does not make it any less shameless by the way. That makes it more shameless.