Org chart

Org chart

/ɔːg ʧɑːt/ (n.)

|

Office anthropology™

|

“What you see is all there is.”

“Der Teufel mag im Detail stecken, aber Gott steckt in den Lücken.”[1]

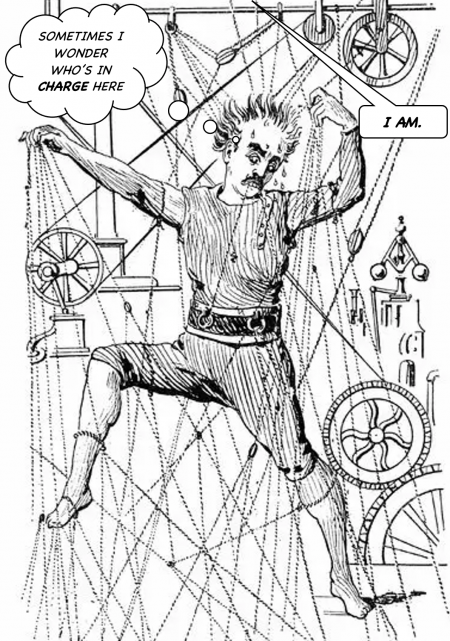

A glib schematic that tells you everything you don’t need to know about an organisation, but which the organisation treats as its most utmost secret.

Form, not substance

Because we can see form easily, we imbue it with meaning. We assume the fixed connections we draw between the vertices of our institutions matter: that they are “structural”, because we say they are.

Take the org chart, which places every person in a firm in a logical, hierarchical relationship to everyone else, each one’s life force and licence ultimately emanating from the splayed fingers of the all-powerful CEO. The org chart implies that this spidery lattice of supply-lines, command-chains and communication channels are the ones that matter.

Spans and layers

There is much management theory around the relationship of “spans” and “layers”[2] optimal organisation charts no more than 5 layers of management; no more than 5 direct reports and so on. This, from People Puzzles, is pretty funny:

How many is too many?

Around five direct reports seems to be the optimum number, according to Mark and Alison, although there are some scenarios where up to nine can work.

When it comes to the senior team in a company, however, too many people reporting directly to the owner manager can really hold the business back. Alison recalls working with someone who had 13 people reporting directly to her. “She had to do 13 appraisals at the end of every year!” she says. “It simply wasn’t an effective use of her time.”

Witness the formalist disposition, when the most significant thing you can do is manage, and the most significant part of management is appraisal. The ethos is this: look after the form and the substance will look after itself. Take care of the pennies and the pounds look after themselves. But this is to look after the pounds, and to assume the pennies will take care of themselves. Well, of course they will: that’s what pennies do: they need no licence from the boss for that.

Hypothesis therefore: performance comes despite management, not because of it.

Management focuses on reporting lines — formal organisational structure — because it can see them. They are legible. They are measurable. Auditable. There are spans and layers, to be counted and optimised. In this way can those at the top conveniently attribute business success to the formal structure they preside over.

But formal reporting lines are the most sclerotic, rusty and resented interaction channels in the organisation. They are the “keep off the grass” signs; vain attempts to coerce inferior modes of communication at the expense of better ones, for if they really were the best lines of communication, you wouldn’t need to formalise them and call them “reporting lines”. They would just happen.

Communications up and down the chain of command — reluctant, strained, for the sake of it, to fulfil formal, not substantive, requirements for order — are reactive to commercial imperatives: the firm’s real business is done only when its gears are engaged, and that means its personnel communicate with those who are not in their immediate hierarchy. The business unit is a cog: what matters is what happens when it is engaged.

But as the complicatedness of our organisations has grown we have developed more and more internal “engines” that engage not with the outside world, but with each other, generating their own heat, noise and movement — frictions and vibrations which wear out parts and fatigue the machinery — and which are lost as entropic energy. Of course, of course: one must have legal, compliance and internal audit, but when those departments have their own operational infrastructure and are themselves monitored and audited, the drift from optimal efficiency is plain. Internal audit must periodically audit itself. But who audits that function? Turtles ahoy: we approach an infinite regression.

The map and the territory

Reporting lines mistake the map for the territory. It is a static map of the firm, configured in the abstract, at rest. That is, before it does anything. This is how the machine works when it is idling.

Org charts: the plan you have before you get punched in the mouth.

But the organisation’s resting state overlooks its real arterial network: lateral interactions that must cross whatever boundaries management can dream up, or that leave the firm altogether: these are the communications that employees must make: between internal specialists in different departments; with the firm’s clients and external suppliers — they make commerce happen and move the organisation along. It is in these interactions that things happen: it is here that tensions manifest themselves, problems emerge and opportunities arise, and here that these things are resolved. These are not the drill, but the hole in the wall.

These are informal interactions. They are not well-documented, nor from above, well-understood. They are hard to see. They are illegible. Yet, everyone who has worked in a large organisation knows that there are a small number of key people, usually not occupying formally significant roles — they are too busy getting things done for that — who keep the whole place running. These “super-nodes” know histories, have networks, intuitively understand how the organisation really works, what you have to do and who you have to speak to to get things done. These are the ad hoc mechanics who keep the the superstructure on the road.

Often management won’t have much idea who these “super-nodes” are, precisely because they do not derive their significance from their formal status, but from their informal function. They earn this reputation daily, interaction by interaction.

A bottom-up map of functional interactions would disregard the artificial cascade of formal authority in favour of informal credibility. It would reveal the organisation as a point-to-point multi-nodal network, far richer than the flimsy frame indicated by the org chart. With modern data analytics, it would not even be hard to do: Log the firm’s communication records for data to see where those communications go: who chats with whom? who calls whom? Who emails whom? What is the informal structure of the firm? Who are the major nodes?

Modernism vs. agilism

The modernist sees the firm is a unitary machine that must be centrally managed and controlled from the top: the more organisational structure the better. The “agilist” advocates removing layers, disestablishing silos, and decluttering the organisational structure. Don’t rely on those senior managers: get rid of them.

The agile theory is that risks and opportunities arise unexpectedly, in places unanticipated by the formal management structure. The optimal organising principle is: allow talented subject matter experts flexibility and discretion to react to those risks and opportunities. Have the best people, with the best equipment, in the best place to react skilfully. Those people aren’t middle managers, the optimal equipment isn’t necessarily the one that leaves the best audit trail, and that place is not the board room, nor the steering committee or the operating committee.

It is out there in the jungle. Management should seek the fewest number of formal impediments to the creative behaviour of those people.

So to understand a business one needs not understand its formal structure, but its informal structure: not the roles but the people who fill them: who are the key people whom others go to to help get things done; to break through logjams, to ensure the management is on side?

These lines will not show up in any organisational structure. They are not what James C. Scott would describe as legible. They are hard to see: they are the beaten tracks through the jungle: the neural pathways that light up when the machine is thinking. They show up in email traffic, phone records, swipecode data.

See also

References

- ↑ The Devil may be in the detail, but God is in the gaps.

- ↑ Let me google that for you.