Document risk

Document risk

/ˈdɒkjʊmənt rɪsk/ (n.)

The devil is not in the detail. The devil is the detail.

The risk to an organisation — overstated in the collective, but wildly understated in the particular — that it loses money because its legal contracts with its customers aren’t “strong” enough.

The usual way of defending against document risk is to treat each customer contract as if it were a communiqué between hostile nations, drawn up in a last-ditch bid to avoid bloodshed on the eve of war.

The documentation of basic trading arrangements between financial counterparties is not so much a cottage industry as a military industrial complex on which the industry spends at least hundreds of millions, if not billions of dollars each year.Our evidence is purely, but compendiously, anecdotal: client documents are wonderful in the abstract, just as long as you never have a concrete need to look at them.

For if you treat a customer like a criminal it will tend to behave like one. If your early draft looks like a rap sheet, by the time your contract is concluded, it will look less like the exchange of lavender-scented love letters it should, and more like downtown Beirut in 1976, just after a vigorous shelling.

A colossal portfolio of battle-tempered contracts bestows great comfort on personnel in credit and legal, notwithstanding all the rubble. It says, in the round, that the firm has laboured hard to defend its interests: all bad things that might come to pass have been anticipated by the battery of preternaturally paranoid negotiation specialists they have at their disposal.

One incomprehensible, bullet-riddled tract is a tragedy; a hundred thousand of them are a statistic: a statistic that by its very existence seems healthy, speaking as it appears to, to the overwhelming diligence with which the firm manages its documentary risk.

Only a fool rushes in to pop a credit officer’s balloon, but foolishness has never stopped the JC before, so here goes: we say this is a false comfort.

They were forged, as we have said, in a series of guerrilla skirmishes in a white-hot urban conflict. The parties to this conflict are battle-hardened commandos, on both sides, learned in all manner of calamities that, in the history of the world, have ever befallen a trading relationship. Each carries a potted history of her own firm’s calumnies called a “playbook”.

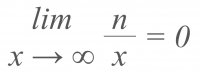

But if you divide all of recorded history (n) by the infinity that is yet to pass (x), the quotient is nought. The calamities of the future bear no necessary resemblance to the disasters of the past.

But when the fog of war rolls in, unspeakable things happen. The normal rules of polite society give way to the furious, pragmatic, law of the jungle. You do not stand on ceremony when you are shipping sniper fire in a bombed-out basement: there is a single objective: to get out alive. A negotiator knows, faintly, that once this fire-fight is over the documents over which she labours will be put away, and no-one will look at them again.

For the great majority of all negotiated contracts, this is but practical common sense. They will never be looked at again. No one may know, we cannot tell, what pains they had to bear.

No-one reads a concluded ISDA Master Agreement out of passing interest. One does it, reluctantly, under pressure, without context, when chips are down at the request of senior executives withins for ice-cold clarity on questions which appear to invite the answer “it is hard to say”. Actually reading concluded customer contracts, especially with a view to doing something with them, is a chastening experience.

We have a theory that the emergence of the hyper-connected global financial markets, though made possible by technology (analog-to-digital revolution, the networked economy and so on), is premised on the post-communist Fukuyaman conviction that the major ideological disputes are over and completing the global liberal democratic project is a matter of working out final minor details. The End of History and the Last Man was published in the same year as the 1992 ISDA. The Lexus and the Olive Tree seven years later.

At the End of History there is a technological solution for everything, and war between nations in the same global supply chain is impossible,[1] since the benefits of co-operative commerce outweigh the benefits of armed conflict. The externalities trading agreements must deal with are matters of human hubris: insolvency and corporate mismanagement; illiquidity; credit; change in laws; foreseeable changes in conditions within the operating parameters of the market.

Our recent history is peppered socio-political events happening beyond those parameters: the shattering of the postwar political consensus with Brexit; a total, worldwide, indefinite lockdown in response to COVID; the reconstitution of 20th century lines of conflict and the potential for nuclear war with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. None of these were, in ordinary contemplation, thinkable before they happened. All happened with alarming speed. Somehow the market has adapted, without legal help from contracts and in many cases in spite of it.

See also

- ↑ Among Thomas Friedman’s hot takes are “No two countries that have a McDonald’s franchise have fought a war against each other since each got its McDonald’s”, later updated to “No two countries that are both part of a major global supply chain, will ever fight a war against each other as long as they are both part of the same global supply chain.” Neither has aged well.