Tier 1 capital

Of a regulated financial institution, the capital level below everything else than gives comfort to the creditors — in particular, its depositors — that those debts will be met. The most obvious type of tier one capital is the institution’s share capital — “tier 1 common equity”. But also is alternative tier 1 capital, also known as AT1, eighty-one, which takes the form of contingent convertible securities (“co-cos”). It became clear in March 2023 when Credit Suisse finally gave up the ghost, that many in the market, including its AT1 investors, didn’t fabulously understand how it worked. (In fairness to them, it wasn’t obvious, even though it was written into the terms and even the title of the AT1 Notes).

|

Regulatory Capital Anatomy™

The JC’s untutored thoughts on how bank capital works.

Here is what, NiGEL, our cheeky little GPT3 chatbot had to say when asked to explain:

|

Alternative tier 1 capital

Debit Suisse and the irate bondholders

Famously, in that panicked Spring weekend in 2023 when it slipped into history[1] the “trinity” of Swiss regulators put a gun to UBS’s head, forced it to make an honest bank of Credit Suisse in a process in which it absorbed Lucky’s equity, and the jewels and hellish instruments of madness and torture secreted around its balance sheet — other than its AT1s. The regulators instead, by ordinance, directed Lucky to write down its to zero.

This — and there isn’t really a delicate way to put this, readers so let’s just come out with it — pissed the AT1 noteholders the hell off.

Their indignance was largely driven by foundational conceptions of what subordinated debt securities are meant to be — that is, senior to shareholders — rather than even a cursory glance at the terms or, goddammit, even the title of their Notes.

They were fortified in their dudgeon by other central bankers (BOE, ECB, the Fed) unhelpfully announcing, for the record, that that is not how they would expect to treat AT1s (you can just imagine FINMA honchos going “yeah, thanks Pal,” when a central banker from Greece — yes, yes, that Greece — went on record as saying “well needless to say we’d never do anything like that. We Greeks are civilised, not like the Swiss!”[2]) and now ambulance chasing litigators are whipping up even more foment, indelicately trawling LinkedIn to raise a pitchfork mob of aggrieved investors to go and sue — well, it isn’t clear who they would sue, or for what, since this was done by legislation — and even the normally mild-mannered financial analyst commentariat has been periodically erupting into virtual fist-fights about what the AT1s do or do not say.

Meanwhile, from the investors, lots of jilted lover energy: “How could I ever trust a central banker again?” sort of thing, and lots of “who knew Switzerland was a banana republic?” vibes, too.

Now the JC likes Switzerland, so he is staying right out of that debate: There are plenty of thought pieces from those more learned and temperate than the JC about that.

But still

But the conceptual question this all throws up, in the abstract, is an interesting one: should creditors, however subordinated, ever rank behind common shareholders? Surely not?

Everyone knew AT1s could get converted into equity, at which point they rank equally with shareholders, and even written off — but there seemed to be the expectation that a write-off would only happen if common shareholders are getting written off too.

First, a little spoiler: effectively ranking behind shareholders and actually ranking behind shareholders feel similar — especially if you have just been written down to zero while the shareholders live to see another day — but they are quite different things.

Two spoilers, in fact: issuers must have contemplated writing AT1s down while shareholders survived: otherwise, why even have a write-down option? A write-down contingent on total shareholder annihilation is no different from a normal conversion to equity: you get what the shareholders get: zero. That kind of write-down option would be meaningless.

The whole point of a write down to zero is to deliver a capital buffer and stave off an insolvency so the corporation can carry on. If it succeeds, the shareholders will live to see another day.

So the JC thinks those central banks who are on record as saying “we’d never write off AT1s before shareholders” are flat out wrong.

A corporation’s shareholders take all the profit and all the losses of the undertaking. You can only work out what those profit and losses are once every other claim on the enterprise has been settled. Those other claims have the feature of being debtor claims. Debtor claims all have defined payoffs; equity claims are, “whatever’s left”.

So, when resolving a company that has gone bust, you must deal with AT1 creditors before you finally settle up with shareholders. You can do this two ways: you can convert the AT1s into shares or, if its terms permit, you can just write them off altogether. Either way, by the time you deal with shareholders, no AT1s are left. Only shareholders remain.

Therefore, the AT1 investors do not actually rank behind shareholders. They can’t. They either become shareholders, or they are goneski. If they get converted into shares they may get some recovery, but only once all the company’s other creditors have been repaid in full. A written down AT1 has been paid in full. The liability was just zero.

But AT1 investors whose notes are written off still feel as if they are effectively ranking behind shareholders. This is because they get nothing and shareholders get something.

But is that really true?

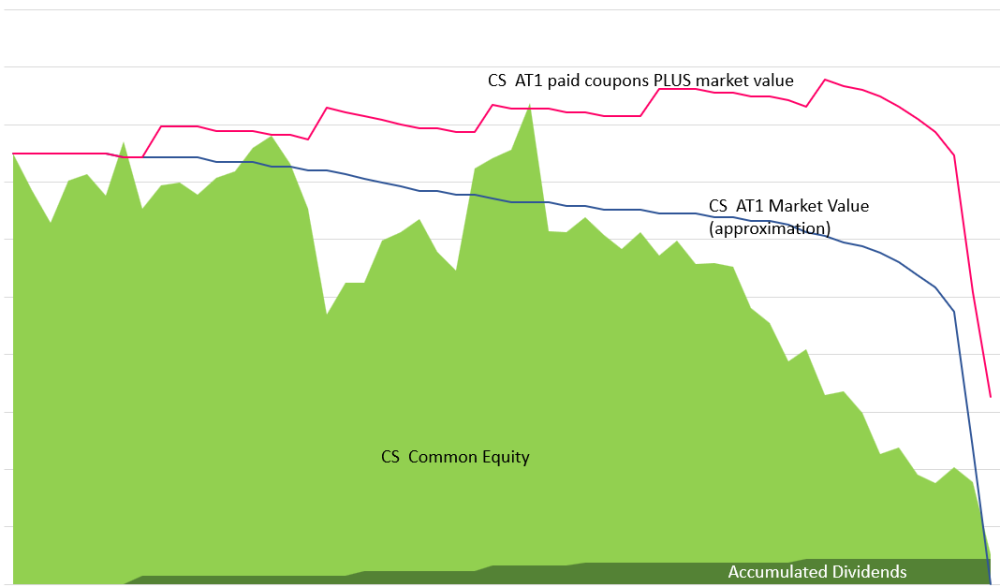

The panel above illustrates our best guess of the cumulative shareholder return — the diminishing cash dividends paid plus ongoing share price, which was in of course in insistent decline over 5 years — and cumulative AT1 return, which is a a much fatter, fixed coupon plus its market redemption value , which we have just made up, but on the premise that until things get truly dire, it will stay somewhere near par. It was trading at 25% on the last trading day before it was vapourised.

The obvious thing about this is that, for a buy and hold, long term investor, it's return has been better than the common equity, including after it was nixed. The combined coupons since issue are easily more than the final acquisition price. In all circumstances except a thermonuclear meltdown the Cocos were a vastly better investment.

“Ah yes, you counter, but tell that the the distressed investors who bought the AT1s on Saturday.

And we should not feel undue sympathy for distressed — ahem vultures — looking to buy a 7% fixed instrument for cents on the dollar when the issuer is in the midst of a well telegraphed existential meltdown? We should not. Even if the ones who did read the prospectus.

The tier one capital layer is there to protect depositors and vouchsafe the stability of the wider financial system, whose collected interests are best served by the bank remaining a going concern. That they happen to share that interest with the banks ordinary shareholders is beside the point. The bonds reward long-term investors — those who read the terms and clocked that “Perpetual Tier 1 Contingent Write-Down Capital Notes” meant these were notes that could be written down in a time of capital stress — most likely had a bank to sell last week.

It sounds like there were plenty of buyers.

See also

References

- ↑ We have a sense Credit Suisse’s history is not done just yet but that, like Disaster Area frontman Hotblack Desiato, it is merely spending a year dead for tax (and, er regulatory capital) purposes. It may well be back, at least as a high-street banking brand in Switzerland.

- ↑ This is a paraphrase, and an exaggeration for effect, I freely admit.