Tier 1 capital

Tier 1 capital

/tɪə wʌn ˈkæpɪtl/ (n.)

|

Regulatory Capital Anatomy™

The JC’s untutored thoughts on how bank capital works.

Here is what, NiGEL, our cheeky little GPT3 chatbot had to say when asked to explain:

|

Of a regulated financial institution, the capital level below everything else that gives comfort to the bank’s creditors — in particular, its depositors — that their debts will be met and deposit withdrawals honoured.

If you are a regulated financial institution (a bank) — but only if you are one of those — you must “hold” a certain percentage of tier 1 capital.

Pedantry alert

There is a certain type of financial analyst who get annoyed if you say banks “hold” capital, for the pedantic reason that capital is a really just what is left of your assets after you deduct your liabilities, and isn’t something you “hold”, as such. It is a difference between two other things, rather than a thing in itself.

Less pedantic types feel that since you have to monitor that difference every day, and do something, like issuing more tier 1 capital securities, if it isn’t there, this isn’t really a distinction worth getting het up about.

But that pedantic distinction can be important, as we will see.

Now: what are “tier 1 capital securities,” then?

Tier 1 common equity

The classic type of tier 1 capital is an institution’s ordinary share capital. This is known, by the same people who know coronavirus as “COVID-19”, as “tier 1 common equity”, or “CET1”.

Until 2008, that is all there really was.

Then the global financial crisis happened, and the global community of bank regulators and their assorted committees, councils and forums got together, promulgated a largely coordinated set of bank resolution and recovery regimes, in the process savagely increasing tier one capital requirements with which banks had to comply.

Alternative tier 1 capital

When banks complained about this — equity capital is quite the drag on performance — regulators conceded there could be a layer of tier 1 capital which wasn’t actually common equity, but could be made to behave like it, should a bank’s chips ever got really down.

On the good days, this layer could behave a lot like debt: it could pay fixed coupons, and redeem — if it redeemed — at par. If things got gnarly, it could convert into common equity, or just go away altogether. Cite error: Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag

AT1 capital takes the form of interest-bearing subordinated debt which the bank may, but need not, call after a few years, As such, from an investor’s perspective, it is perpetual in the same way ordinary shares are. But banks can decide to repay it, at par, if they like. This they will only do if times are good and it is cheap to issue more AT1 capital.

Why does it count as tier 1 capital then? Because it contains an embedded, “contingent,” bomb.

In certain disaster scenarios it is convertible into ordinary shares, at which point it becomes CET1, or may even be written off altogether. To zero. A duck. Bupkis.

Conversions and write-downs are “contingent” on defined events — der Teufel mag im Detail stecken to the max — things like capital thresholds being breached, or regulators concluding the bank is not viable otherwise — so AT1s are also called “contingent convertible securities” or “co-cos”.

It became clear in March 2023 when Credit Suisse finally gave up the ghost, that many in the market, including AT1 investors, didn’t fabulously understand how they worked.

Debit Suisse and the irate noteholders: co-co go loco

Famously, in that panicked spring weekend in 2023 when it slipped into history[1] the “trinity” of Swiss regulators put a gun to UBS’s head, forced it to absorb Lucky’s equity (and all the baubles, jewels and hellish instruments of madness and torture embedded in it) — and, by ordinance, directed Lucky to write down its AT1s — which were “Perpetual Tier 1 Contingent Write-Down Capital Notes,” and names are important here — to zero.

This — and there isn’t really a delicate way to put this, readers, so let’s just come out with it — pissed the AT1 noteholders the hell off.

Their indignance was largely driven by foundational conceptions of what subordinated debt securities are meant to be — that is, senior to equity — rather than even a cursory glance at the terms or, goddammit, even the title of their Notes. This, from the termsheet, gives a clue:

If a Contingency Event, or prior to a Statutory Loss Absorption Date, a Viability Event occurs, the full principal amount of the Notes will be mandatorily and permanently written down. The Notes are not convertible into shares of the Issuer upon the occurrence of a Contingency Event or a Viability Event or at the option of the Holders at any time. [2]

But, docs schmocks.

Wounded AT1 holders were fortified in their dudgeon by other central bankers (BOE, ECB, the Fed) unhelpfully chipping in, saying, for the record, that that is not how they would expect to treat AT1s. You can just imagine FINMA honchos going, “yeah, thanks, Pal,” when a central banker from Greece — yes, yes, that Greece — remarked “well, needless to say we’d never do anything like that. We Greeks are civilised, not like the Swiss!”[3]

Now ambulance chasing litigators are whipping up even more foment, indelicately trawling LinkedIn to raise a pitchfork mob of aggrieved investors to go and sue — well, it isn’t clear who they would sue, or for what, since this was done by legislation — and even the normally mild-mannered financial analyst commentariat has been periodically erupting into virtual fist-fights about what the AT1s do or do not say and whether a trigger event did or did not happen.

Meanwhile, from the investors, there is lots of jilted lover energy: “how could I ever trust a central banker again?” sort of thing, and lots of “who knew Switzerland was a banana republic?” vibes, too.

Now the JC likes Switzerland, so he is staying right out of that debate: There are plenty of thought pieces from those more learned and temperate than the JC about that. But Switzerland is not a banana republic, and it is known for its banking acumen. This, we think, will be borne out over time.

On creditors ranking behind equity-holders, feelings and so on.

But the conceptual question this all throws up, in the abstract, is an interesting one: should creditors, however subordinated, ever rank behind common shareholders?

Surely not?

Everyone knows AT1s can get converted into equity, at which point they rank equally with shareholders, and even written off — but there seemed to be the expectation that a write-off would only happen if common shareholders are getting written off too.

First, a little spoiler: effectively ranking behind shareholders and actually ranking behind shareholders may feel similar — especially if you have just been written down to zero while the shareholders live to see another day — but they are different things. When an is written down AT1 down to zero, its creditors actually rank ahead of shareholders. It is just that their claim is zero.

Another spoiler: this cannot have come as a surprise. Issuers must have contemplated writing AT1s down while shareholders survived: otherwise, why even have write-down Notes? A write-down contingent on total shareholder annihilation is no different from a normal conversion to equity: you get what the shareholders get: zero. If that is all you wanted, you would just issue normal contingent convertible bonds. But these AT1s were not convertible. There were “Perpetual Tier-1 Contingent Write-Down Capital Notes”. Again, that name. Important.

The whole point of writing down AT1s is to deliver a capital buffer and stave off an insolvency so the bank can carry on.

Pedantry redux

This is where that pedantry we mentioned at the top is important: “capital” is not a thing: it is a difference between things. If the AT1s are vaporised, it follows that the tier 1 capital — now comprising only common equity — is worth 17bn more. If the Write-Down succeeds, the shareholders will live to see another day.

So the JC thinks those central banks who are on record as saying “we’d never write off AT1s before shareholders” are flat out wrong.

A corporation’s shareholders take all the profit and all the losses of the undertaking. You can only work out what those profit and losses are once every other claim on the enterprise has been settled. Those other claims have the feature of being debtor claims. Debtor claims all have defined payoffs; equity claims are, “whatever’s left”.

So, when resolving a company that has gone bust, you must deal with AT1 creditors before you finally settle up with shareholders. You can do this two ways: you can convert the AT1s into shares or, if its terms permit, you can just write them off altogether. Either way, by the time you deal with shareholders, no AT1s are left. Only shareholders remain.

Therefore, the AT1 investors do not actually rank behind shareholders. They can’t. They either become shareholders, or they are goneski. If they get converted into shares they may get some recovery, but only once all the company’s other creditors have been repaid in full. A written down AT1 has been paid in full. The liability was just zero.

Did the AT1s really do worse than common equity?

But AT1 investors whose notes are written off still feel as if they are effectively ranking behind shareholders. This is their lived experience: they get nothing and shareholders get something.

But is that really true?

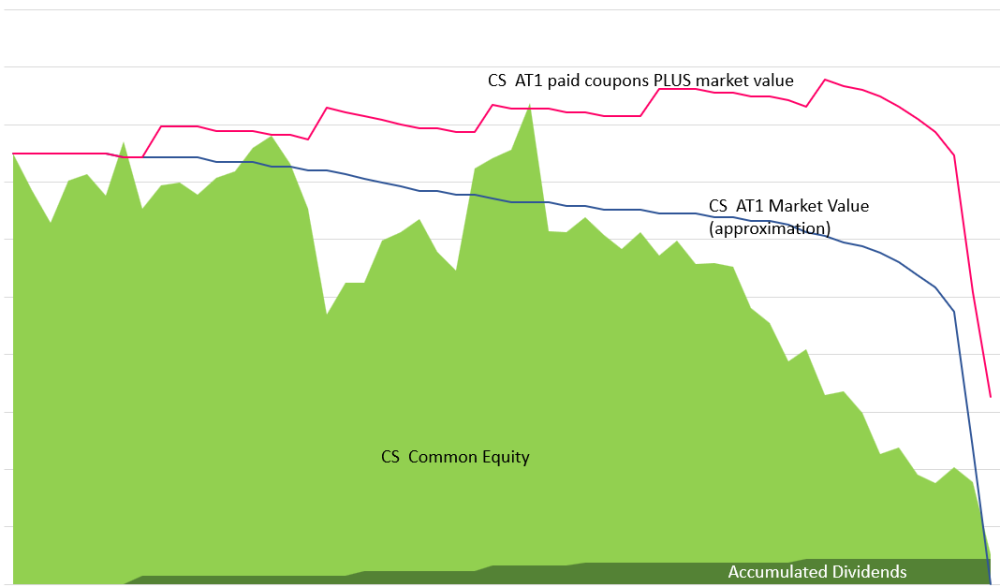

The graphic in the panel above illustrates our best guess of Credit Suisse’s own cumulative shareholder return against the 7.25% Write Down Notes issued in September 2018. You can see the diminishing cash dividends paid plus ongoing share price, which was in insistent decline over 5 years — compared with the cumulative AT1 return, with those much fatter, fixed coupons plus the AT1s’ market value, which we just made up, on the premise that until things got truly dire, it would have been somewhere near par. they were vaporised.

The thing to notice here is that, for a buy-and-hold, long-term investor, the AT1s’ return, event after they were nixed, was miles better than the common equity. The accumulated coupons since issue totalled about a third of its issue price. That is far more than the final acquisition price for the common equity.

And this is not just true of Credit Suisse: this was true across the board, as Lucky’s own research indicated:

From the pooch’s mouth: cocos really are better than equity. Over time.

|

On talking your own book

“Ah yes,” you counter, “but just try telling that the distressed investors who bought their AT1s last Saturday.”

Now: should we feel sympathy for distressed investors who buy a 7.25% capital instrument for 20 cents on the dollar, during a well-telegraphed existential meltdown, and find themselves wiped out?

We should not. Especially those who didn’t read the prospectus.

Should we expect hotshot hedgies who have just taken a shellacking to have good graces about it, and to publicly concede that, well, them’s the breaks, and these things happen?

We should not. Even those who did read the prospectus.

Should we expect class action litigators to hold public zoom calls to tell everyone to just calm the hell down and put their big-boy pants on and take the loss like adults, being grateful as they go that the system worked quickly and effectively to ensure the continued solvency of a systemically important financial institution?

We should not.

On the difference between equity and debt investment

One invests in shares to take advantage of rapidly changing market conditions. A share price is a capricious, will o’ the wisp sort of thing: it flits about, impishly, by driven by the unpredictable humours and phantoms in the market’s deep subconscious, whether they be fundamental, structural, geopolitical, or psychological in nature, or just the product of the periodic madness of crowds.

One can, and many do, make a living trading short-term movements in shares.

In ordinary times, debt instruments — even AT1s — are much less volatile. They do not hop about much, day-to-day. They are sensitive to interest rates and the ultimate solvency of their issuer but as long as that isn’t seriously in question their value does not jump around. Their main attraction lies the scheduled interest they pay.[4] Investors benefit from bet instruments over time.

This is equally true of AT1s. They reward long-term investment.

In ordinary times, their return is a linear function of how long you hold them. While you hold them you are funding the bank’s tier 1 capital cushion. That is a long-term exercise.

It is different in a distressed scenario. Here, AT1s are unusually vulnerable: this is the very contingency they are designed to protect the bank — not the investor; the bank — against. As the bank’s capital ratio approaches the trigger threshold, AT1s behave more like equity.

Convertible AT1s, in their worst case, become common equity. Their value will converge on the common equity exactly.

Write-Down AT1s, in their worst case, become zero. In times of stress we should expect them to be even more volatile than common equity. They are, effectively, binary options: if they are triggered, they disappear. If they are not, they will eventually be called at 100 and, in the meantime, will continue to pay fat slugs of interest.

Indeed, this is exactly what we saw.

So, we should not feel bad for opportunistic speculators who picked up the AT1s for a song, but got hosed. This is exactly the bet they were taking.

Should we feel bad for loyal investors who bought at issue, held till the death and were written down to zero?

Again, no. Over the life of their investment, they did much better than common equity holders. Look at the chart in the panel. They may regret being written down, but that is exactly the option they sold when they bought the Notes.

Financial stability wins ... for now

It boils down to this: the alternative tier 1 capital layer is there to protect depositors and ensure the stability of the wider financial system, by helping banks to remain a going concern even in times of great stress. That the bank’s ordinary shareholders happen to share that interest is beside the point. AT1s are meant to reward, and did reward, long-term investors.

The AT1 holders who, last week, understood that “Perpetual Tier 1 Contingent Write-Down Capital Notes” meant their notes could be written down in a time of capital stress had a bank to sell .

It sounds like there were plenty of buyers.

See also

References

- ↑ We have a sense Credit Suisse’s history is not done just yet but that, like Disaster Area frontman Hotblack Desiato, it is merely spending a year dead for tax (and, er regulatory capital) purposes. It may well be back, at least as a high-street banking brand in Switzerland.

- ↑ Emphasis added. Full documents here.

- ↑ This is a paraphrase, and an exaggeration for effect, I freely admit. [Full interview here.

- ↑ Or amortisation yield, for zero-coupon instruments.