Incluso

Incluso

/ɪnˈkluzəʊ (n.)

The opposite of a proviso. A proviso may be a ginger, lilly-livered construction, but at least it does something: it states a proposition and then weasels out of it:

|

The JC’s guide to writing nice.™

|

- The promisor herewith agrees to pay, unconditionally and in full, all amounts due, provided that on no account shall such promisor be liable for: ... [here follows a catalogue of exceptions great and small the sum total of which will equal, or perhaps even exceed, the value of the commitment so generously given].

An incluso, by contrast, states that proposition, and then illustratively repeats it, bearing useful confirmation only to those who enjoy miscellany or are afflicted by doubt as to whether you meant what you said in the first place:

- We will send such confirmations and information in such form (including paper, writing, parchment, scrolls, hand-signals, facial tics, morse code, semaphore, maritime signalling systems or other symbolic languages (whether or not depending for their efficacy upon the assistance and/or configuration of flags) as we shall determine from time to time.

A well-crafted incluso will drag into contemplation items which no ordinary reading of the general principle could possibly have anticipated.

The nested incluso

A seasoned practitioner will enjoy the nested incluso, where one redundant elucidation is embedded into another:

- “the Client shall pay the Bank’s costs of enforcement (including, without limitation, filing fees, the costs of realisation of collateral and professional fees (including, without limitation, those of its legal, accounting, tax and other advisors) ...)”

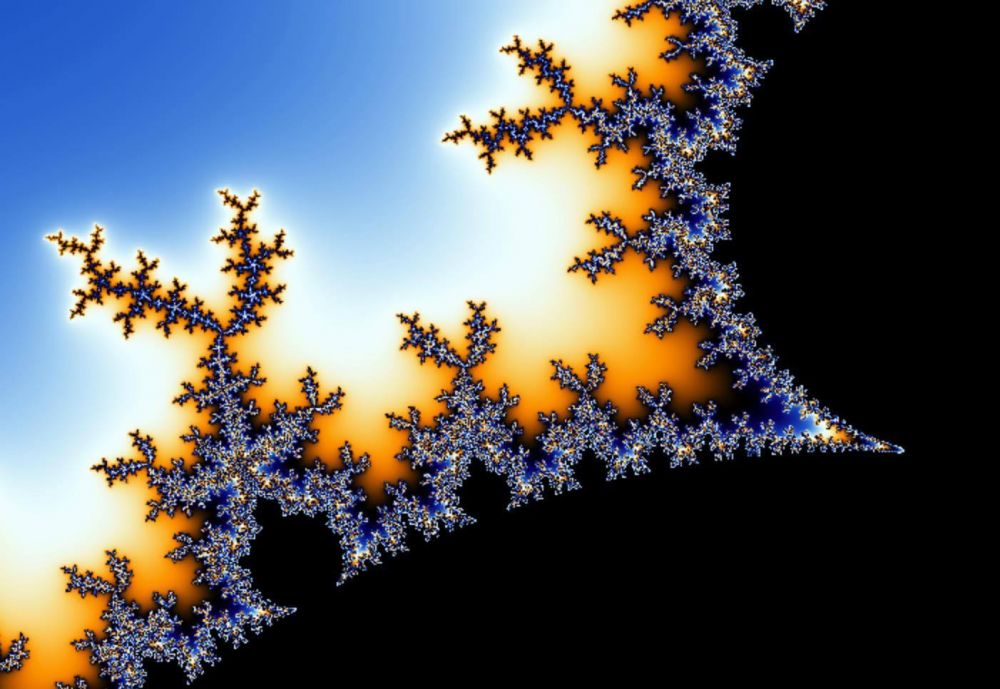

Here we can see at once that this way a rabbit-hole lies, and down it the theoretical possibility of an unbroken chain of ever-smaller inclusos, stretching out into an infinite panoply of parenthetical asides; a kind of fractal geometry of scale-invariant pointlessness, whose existence in this universe is only really hindered by the outright fear that, far from the sky falling on one’s head, instead you might inadvertently have warped the very fabric of semantic space itself, in a way which could swallow you up and regurgitate you in some remote corner of the lexiverse as a spume of incandescent flannel. Thanks to the Fish principle, the scope for nested inclusos is, literally, infinite but as you go they converge asymptotically on the Biggs constant — the point at which incremental legal mark-up can no not be less significant without losing all meaning whatsoever.

The provuso

The sign of a true legal master is the provuso, which is an amalgam of a proviso and an incluso, a device by which one states a general principle, then caveats it so comprehensively that the end result bears no correlation at all with the originally intended. This is a way of weaselling your counterparty into a whole new obligation that it did not have in mind when discussing the original trade, while at the same time yourself wriggling out of your basic economic commitment.

The definition that isn’t

A further, unremarked-upon use of includes is in a definition, to capture something that really goes without saying, but which the fussy clerk can’t quite bring herself to let go. So, for example, ISDA’s crack drafting squad™ half-hearted definition of “law”.

Now of all people you, would think a bunch of lawyers would know a law when they see one, but when it comes to the squad you can never be too careful. Nor should one arbitrarily restrict oneself to one’s field of competence — for who knows what sort of things could, under some conditions, from particular angles and in certain lights be for all intents and purposes laws even if, for other times and other peoples, they might not be? The answer is to set out the basic, sufficient conditions to count as a “law”, without ruling out other contrivances that one might also like to regard as laws, should the context recommend them. Here, using “includes” instead of “means” fits the bill admirably.