Interest rate swap mis-selling scandal

Weird things were happening in the interest rate markets which had been pretty stable since — well, the Glorious Revolution:

|

Chez Guevara — Dining in style at the Disaster Café™

|

Nine banks including Lloyds, RBS and HSBC agreed in 2013 to compensate companies that were sold inappropriate products that were supposed to protect them from changing interest rates on their debts. However, these hedges could expose the firm to the risk of rate movements even after their initial loan had been repaid.

- — Daily Telegraph, 10 February 2015

In 2008, interest rates plummeted and thousands of customers found the mark-to-market value of their IRHPs materially changed, leaving them with significant losses if those IRHPs terminated early. Alternatively, customers were tied in under the IRHP contracts to pay far higher interest rates than the prevailing market rate for years to come; in some cases the IRHP contract terms extended well beyond the period of the underlying loan.

- — Swift Review into the supervisory intervention on interest rate hedging products

The interest rate environment in the early 2000s

For two hundred years the Rate hovered between 2 and 10 per cent, and in the gloom of Threadneedles’ cave, it waited. Darkness crept back into the forests of the world. Rumour grew of a shadow in the East. Whispers of a nameless fear. And the Rate of Power perceived its time had come.

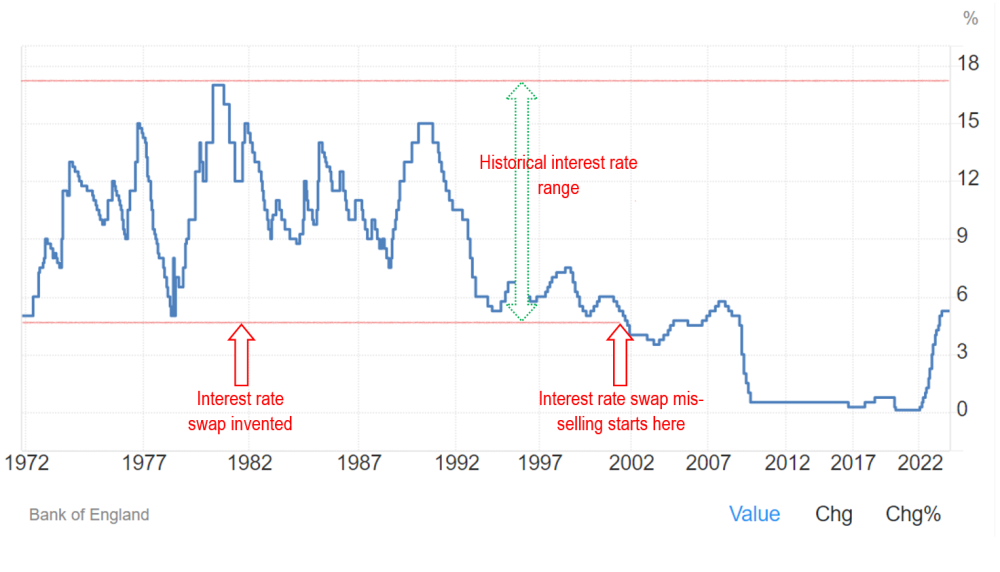

Since the early seventies, interest rates had bounced around between about 8 and 15 per cent. But after a brief spike when the UK unceremoniously exited the Exchange Rate Mechanism in 1992 they fell towards thirty-year lows. As the Cool Britannia vibe suffused the nation and Gordon Brown banished boom and bust [subs: can we check this?] rates stayed abnormally low, around six per cent.

In the meantime some bright sparks at Salomon Brothers had invented the One ring to bring them all and in the darkness bind them swap and the era of Sauron tradable interest rate derivatives was upon us.

JC has written elsewhere about the revolutionary confluence of technologies that led to the interest rate derivatives market What didn’t change — what hasn’t changed since the invention of credit, and which will not change until the apocalypse, is a business’s basic need borrow funds for working capital at a predictable cost.

This is a cost of business as inevitable as employees, plant and machinery. Businesses are figured out ways of managing employee costs: discretionary bonuses. These are ostensibly tied to business performance — the better we do the more you get paid — but really are tied to market performance: the higher your bid, the more you get paid.

It would be fun to develop employment derivatives. They would be like interest rate swaps. A bunch of large employers would submit, daily, how much they would be prepared to pay to hire established categories of worker, to derive some kind of London Inter-Employer Bid-Offer Rate (can we call this LIEBOR?). Then the British Human Capital Managers Association would compile and publish a list of rates. Employer could swap out their fixed costs for a floating rate, thereby hedging employment costs. Employees could do the same, hedging against their intrinsic loyalty discount, and restricting employee moves to genuine changes in role, or idiosyncratic hatred of boss, rather than just the need to rebenchmark periodically.

Lest you should think I am joking consider the cost of employment in a large financial services institution might be in the multiple billions.

But we can surmise that businesses seeking to borrow money in 2002 might have been thinking rates were abnormally low, and it might be a good time to lock in an interest rate.

Had swaps not been invented, they might have done this by borrowing at a fixed rate for a fixed term.

Interest rate exposure. Borrowing money? Inevitable.

Fixed rates, of course, also give you exposure to the interest rate market. If you are borrowing money, you have exposure to the interest rate market. Your only question is what kind.

The basic problem of business borrowing is to meet debt servicing costs — interest and principal — out of business revenues. Your incoming revenues are not tightly coupled to interest rates — it isn’t like they move instep or anything — but they are probably related. If interest rated go up, people generally save more, spend less and so business might drop off a bit. But as a general proposition, fixing an interest rate you can afford to service given the general ebb and flow of your revenue, is your best bet.

However, if you fix at ten percent, and then variable rates drop off a cliff, you might be kicking yourself. Sure, you can refinance elsewhere — but there will be some penalty for paying your loan off early. This is precisely because you locked in that fixed rate, and the bank hedged for it, so if you break it, the bank has to break its hedge. Also, a deal’s a deal.

You can manage this a bit by shortening the period for which you borrow. But there’s a tension — the shorter your term the more susceptible you are to higher rates when you come to “roll” your loan.

But the basic crux is this: your interest rate risk is not a function of venal bankers, or bad hedging or anything like that: it is a function of borrowing money. If you don’t want interest rate risk don’t borrow anything.

Note here a fundamental axiom of finance, which JC believes in the derivatives age has been wildly overlooked: an interest rate is not some abstract thing, that exists out there in the wild, by itself, independent of any other activity. It is constitutionally, spiritually bound to the business of borrowing and lending money.

Yes, we have developed clever tools that enable us to see interest rates as discrete, lighter than air things, but this is a misleading picture. All rates, somehow, can be routed back to borrowed money. Interest rate is no more independent of loaned money than a shadow is independent of the boy who casts it, or the light source he stands infront of.

There is an argument that had interest rate swaps not been invented corporate borrowers fixing term loans in 2008 might have been just as badly burned, but would not have had anything to complain about.

The banks

Skulduggery in the LIBOR submission process was not the only saucy carry-on in the interest rate market. For something that is meant to be dullsville, after school chess club was quite the hotbed.

Take the business of lending to small and medium enterprises.

What follows is not authenticated history, but something more like a fable or a “just so” story. A bedtime story. The actual facts of any particular case might differ, but it stands as a simple device to paint a general picture.

Bear in mind what the businesses of middle England want from their banks: finance, for a predictable term, at a predictable cost.

We take it as generally axiomatic that if you want to give, or take, back your money at any time, interest will accrue at a variable rate, and if you want to lock in the borrowing or lending for a term, interest will accrue at a fixed rate.

And remember, in the good old days — specifically before 1981 — if you wanted “exposure” to an interest rate, you had to actually borrow, or lend, money. But England’s businesses didn’t want “exposure to interest rates”. They wanted money. Capital. Indeed, before 1981 the idea of “isolated exposure to interest rates” would have seemed more or less incoherent, the same way a shadow seems incoherent, without the boy who cast it.

Interest came with a loan, and how it was calculated depended on its term: if you wanted your money back at any time without penalty, there was no “term” — well: strictly speaking there was, but it was overnight — and your interest rate could therefore “reset” every day. If you didn’t like the new rate, you could take your money away, or pay it back, without penalty. Hence, interest on call deposits (and revolving credit facilities) is calculated by reference to a floating rate.

If you wanted to lend or borrow for a set term, you could lock in a fixed interest rate for that term — but you couldn’t have your money back, or voluntarily repay it, before that term, either, without incurring a “funding break cost”.

We can see here that interest rate “risk” sits with the bank: it is funding the customer’s loan from its own borrowing — that’s what banks do — and if the cost of that borrowing rises or falls, the bank loses or gains.

This is how it ought to be: banks are the financial experts. They have the size, scale, expertise, information and position to manage their interest rate risk. The caravan parks of Middle England are better spending their energy managing, well, caravan parks.

The great financial innovations of the 1980s led bankers to see their liabilities in a whole new way. A fixed rate loan was a funded credit derivative with an embedded interest rate swap.

This was all well and good — you could see it that way, and with derivatives, you could certainly manage your risk that way — but bankers were still left with the rather unitary problem that their interest rate risk was buried intractably in a term loan.

What if, wondered the bankers, we separated them? We could offer our customers floating rate loans and sell them interest rate swaps, under an ISDA, by which they can convert those floating rates into fixed.

You might be wondering what the appeal of that would be, over a plain old fixed rate loan, for the customer. JC wonders that, too.

The appeal to the banks was obvious. Floating rate loans are easier to fund. But they expose customers to interest rate risk, which neither they, nor their bankers, want: if interest rates go so high as to ruin the customer, the bank is likely to lose money too.

Interest rate swaps are easier to manage. They are managed by different people in the bank.

At about the same time, Britain’s commercial bankers were having fun at the hands of the caravan parks, flying clubs and property investment consortia of middle England. The interest rate swap mis-selling scandal is a many-headed hydra — it turns out most commercial banks in the UK had hit upon variations on the same idea independently of each other and then jammed it down middle England’s gizzard, but the gist was this: rather than just offering them straightforward loans, banks would offer floating rate loans stapled — loosely — to complicated hedging products.

This would be odd enough if it were just a floating rate loan and a fixed rate swap — why not just lend at a fixed rate — but these swaps had all kinds of funky features that didn’t suit any obvious commercial need, and banks sold them often by appealing to the borrowers’ vanity or dubious interest rate risks. A fun example was the “enhanced dual fixed rate protection” under which:

Borrower would pay 5.10%, if interest rates were between 4.75% and 6.25%, and 6% if interest rates were above 6.25% or below 4.75%. Additionally the Bank had the right to terminate without penalty each quarter after five years.

It is not obvious who this protects, or what it enhances, but it does not seem to be the borrower.