I am a Strange Loop

I am a Strange Loop — Douglas Hofstadter

|

A sleight of hand to kill all sleights of hand

Philosophy, to those who are disdainful of it, is a sucker for a priori sleights of hand: purely logical arguments which do not rely for grip on empirical reality, but purport to explain it all the same: chestnuts like “cogito ergo sum”, from which René Descartes concluded a necessary distinction between a non-material soul and the rest of creation.

Douglas Hofstadter is not a philosopher (though he’s friends with one), and in I am a Strange Loop he is mightily disdainful of the discipline and its weakness for cute logical constructions. All of metaphysics is so much bunk, he says, and he sets out to demonstrate this using mathematics and spooky power of Gödel’s incompleteness theory.

Observers may pause and reflect on an irony at once: Hofstadter’s method, derived a priori from the pure logical structure of mathematics, looks rather like one of those tricksy metaphysical musings on which he heaps derision. As his book proceeds, the irony only sharpens.

But I’m getting ahead of myself, for I started out enjoying this book immensely. From about halfway I found it increasingly unconvincing, notably at the point where Hofstadter leaves his (fascinating) mathematical theorising behind and begins applying it. He believes that from purely logical contortion (mathematics) one may derive an account of consciousness as a purely physical phenomenon that is robust enough to bat away any philosophical objections, dualist or otherwise.

Note, with another irony, his industry here: to express the physical parameters of a material brain in terms of purely non-material apparatus (a conceptual language). In the early stages, Professor Hofstadter brushes aside reductionist objections to his scheme which is, by definition, an emergent property of, and therefore unobservable in, the interactions of specific nerves and neurons. Yet late in his book he is at great pains to say that that same material brain cannot, by dint of the laws of physics, be pushed around by a non material thing (a soul), and that configurations of electrons must correspond directly to particular conscious states in what seems a rigorously deterministic way (Hofstadter brusquely dismisses conjectures that your red might not be the same as mine). In his closing pages, Hofstadter seems to declare himself a behaviourist. Given the enlightening work of his early chapters, this comes as a surprise and a disappointment to say the least.

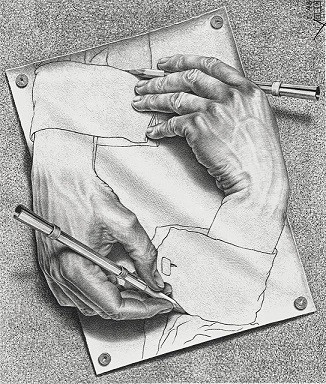

Hofstadter’s exposition of Kurt Gödel’s theory is excellent and its application in the idea of the “strange loop” is fascinating. He spends much of the opening chapters grounding this odd notion, which he says is the key to understanding consciousness as a non-mystical, non-dualistic, scientifically respectable and physically explicable phenomenon. His insight is to root consciousness not in its physical manifestation (the brain), but in the patterns and symbols represented within it. This is all he needs to establish to win his primary argument, namely that artificial intelligence is a valid proposition. But he is obliged to go on because, like evolution in Darwin’s Dangerous Idea, his strange loop is a universal acid and it threatens to cut through many cherished and well-established ideas, and to some of them he seems not quite ready to let go.

The implication of the strange loop, which I don’t think Hofstadter denies, is that a sufficiently complex (and “loopy”) string of symbols embedded in a suitable substrate can yield consciousness as an emergent property. That is a neat idea (though Hofstadter’s support for it is only conceptual, and involves little more than hand-waving and appeals to open-mindedness.)

But all the same, some strange loops began to occur to me here. Perhaps rather than slamming the door on mysticism, Professor Hofstadter has unwittingly blown it wide open. After all, why stop at human consciousness as a complex system? What about a complex system of humans? couldn’t that have its own, independent, emergent consciousness? Shouldn’t it, in fact? Conceptually, perhaps, one might be able to construct a string of symbols representing God. Would it even need a substrate? Might the fact that it is conceptually possible to write a “God string” mean that God therefore exists?

Herein lie the dangers (or irritations) of tricksy a priori contortions. Professor Hofstadter can’t complain about this: he started it.

Less provocatively, perhaps a community of interacting individuals, like a city—after all, a more complex system than a single one, Q.E.D. — might also be conscious. It seems to me it probably would be. This would be no less apparent to us than our consciousness is to one of our neurons. Who knows? Perhaps there are all sorts of consciousnesses which we can’t see precisely because they emerge at a more abstract level than the one we occupy.

This might seem far-fetched, but the leap of faith it requires is no bigger than the one Hofstadter explicitly asks of his reader. He sees the power of Gödel’s insight being that symbolic systems of sufficient complexity ("languages” to you and me) can operate on multiple levels, and if they can be made to reference themselves, the scope for endless fractalising feedback loops is infinite. The same door, that opens the way to consciousness, seems to let all sorts of less appealing apparitions into the room: God, higher levels of consciousness and sentient pieces of paper bootstrap themselves into existence also.

This seems to be a strange loop too far, and I suspect it is why Hofstadter ultimately embraces the reductionism of which he was initially so dismissive, He ends by concluding that there is no consciousness, no free will, and no alternative way of experiencing red. Ultimately he asserts a binary option: unacceptable dualism with all the fairies, spirits, spooks and logical lacunae it implies, or a pretty brutal form of determinist materialism. If that’s the choice, I think I’ll stick with Descartes.

There’s yet another irony in all this, for Hofstadter scorns Bertrand Russell’s failure to see the implications of incompleteness on his formal language, but has a comparable failure to see the same implications for his own theory. Strange loops allow—guarantee, in fact—multiple meanings via analogy and metaphors, and provide no means of adjudicating between them. They undermine, utterly, the idea of transcendent truth. The option isn’t binary at all: rather, it’s a silly question.

In essence, *all* interpretations are metaphorical; even the “literal” ones. Neuroscience, with all its gluons, neurons and so on, is just one more metaphor which we might use to understand an aspect of our world. It will tell us much about the brain, but very little about consciousness, seeing as the two operate on quite different levels of abstraction.

To the extent, therefore, that Douglas Hofstadter concludes that the self is that is an illusion his is a wholly useless conclusion. As he acknowledges, “we” are doomed to “see” the world in terms of “selves"; an a priori sleight-of-hand, no matter how cleverly constructed, which tells us that we’re wrong about that (and that we’re not actually here at all!) does us no good at all.

Neurons, gluons and strange loops have their place—in many places this is a fascinating book, after all—but they won’t give us any purchase on this debate.