Compensation

Compensation /ˌkɒmpɛnˈseɪʃən/ (n.)

Investment banks are equally good at hyperbole and euphemism, the latter being a sort of inverted hyperbole, calculated to make the unseemly seem chaste; the trivial important, the quotidian grandiloquent and the ignoble dignified. Bankers are at their creative best when discussing their own pay. Of their number, none are more given to euphemism, and indeed hyperbole, than the good people of personnel or, as they like to think of themselves, human capital management. You see? They can’t help it.

|

It is they who come up with bright ideas like “rebranding” your salary as, for example, “rewards”.

Now, being given a reward sounds like you’ve won a competition of skill, returned a missing whippet to its owner, or uncomplainingly completed a lifetime of selfless good works. A “reward” is that gold watch; a ticket to heaven; the football that every good boy deserves.

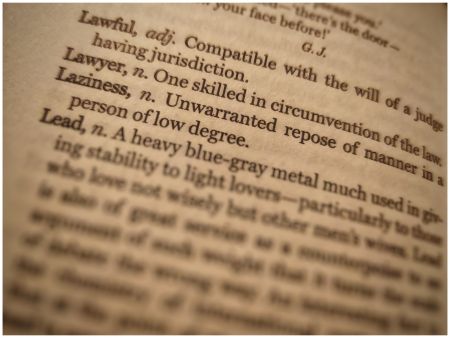

It doesn’t sound much like the filthy lucre that bankers get paid. Once upon a time, “rewards” were called “compensation” — another fine euphemism, but one markedly nearer the bone. After an absence, it is back in vogue. We like it because it makes pay sound a lot closer to what it feels like.

The word “compensation” speaks of redress for wrongs perpetrated. It conveys a salutary attempt at rectification; an act of economic recompense for the unspeakable spiritual ugliness one’s employment demands. “Compensation” implies a forlorn essay at correcting the inexpungible stain of moral compromise.

This, all agree, is the unavoidable price one must pay to persuade good men and women to devote their creative souls to the dark arts of financial service.

But is it? Every agent, however devoted to its principal, has against it the same, aligned, common interest: that, whatever happens, it should continue to be needed, and therefore paid. Do not forget that such a fellow, like the one who hotly insists on imposing gardening leave upon departing colleagues, is, at one remove, talking his own book. This is the agency problem.

And plenty of organisational psychologists have identified better, more plausible drivers for optimised productivity and excellent performance than the discretionary bonus. Daniel Pink has made a fair bit of his own compensation making this very point. Superficially, it is easy to understand why this might be so: the simple amount of energy, infrastructure and human effort that goes into figuring out, down to the dollar, who gets what in itself occupies a month or more of the collective assembled’s time. Here is the proof of the AI pudding by the way: if you think a banker would entrust any part of the compensation allocation process to an algorithm, you have profoundly misunderstood the nature of the beast. And nor can the obsessive secrecy that surrounds compensation be in anyone’s interest. Nor is it consonant, really, with the loudly professed commitment to diversity of pay and conditions.

There is an irony here: you should not underestimate the care and precision with which pay is allocated and promotions are managed at an investment bank. Fastidious does not begin to describe it. Every detail is benchmarked, cross-checked, cross-ruffed, socialised, graded, forced to a curve, scatter-analysed, pivoted, double-blind tested and haggled over. And over this, Personnel and its paramilitary wing the office for diversity and inclusion preside. They run this process, with an iron fist. They are utterly fundamental to it, and always have been. From the perspective of natural justice, procedural fairness, human rights, equal opportunity — it is quite unimpeachable.

Which has left some institutions with a curly question when it transpires that the lion’s share of the spoils, the titles, the promotions and executive suite positions go to straight white men.