Thirteenth law of worker entropy

The JC’s thirteenth law of worker entropy (also known as the “optimal complication theorem”): Over time, a given template will tend to a point of “optimal” complication, (c), which is a function of:

|

Office anthropology™

|

“Je n’ai fait celle-ci plus longue que parce que je n’ai pas eu le loisir de la faire plus courte.”[1]

— Pascal, Lettres Provinciales, 1657.

- (i) the highest plausibly chargeable fraction of the typical value, (vf), of contracts concluded on the template,

- (ii) the time, (t), required to manipulate the template so it reliably works to the satisfaction of one having the patience, skill and hubris to understand it, and

- (iii) the professional charge-out rate, (r), of such an unusually abled person.

The relationship between c, vf, t and r is as follows: c ↔ vf = tr.

The JC developed this over a series of papers [do you mean “beers”? — Ed] with sometime collaborator, poet, playwright and tropical disease victim Otto Büchstein when trying to understand how medium term note documentation could be so dreary despite (a) the underlying product being basically straightforward and (b) repeated efforts by market participants to make it easier.[2]

There are underlying dynamics here.

Firstly, r and t are positively correlated. This follows: the more patience, skill and hubris required to competently manipulate text, the fewer people can do it and, by ordinary principles of supply and demand, the more they can charge.

Hence, pace Blaise Pascal, charge-out rates tends to rise, not fall, with prolixity.

Similarly, v is actual, real-world value, and not “notional fright-value imbued by the neurotic expostulations of paranoid lawyers”. vf, we think, is a cosmological constant.

Thus, a secured medium term note — typically in the tens or hundreds of millions of dollars inprincipal amount — has high intrinsic value even though the basic premise of a transaction — “I lend you money, you give me a an IOU, I can sell it, you repay whoever holds it at maturity, with interest, depending on certain externalities” — is pretty simple.

Thus, you can expect the documentation for a bond deal to span several hundred pages of wretched text, and so it does, notwithstanding that one can, and parties typically do, trade on a one-page term-sheet.

Netting opinions are the same: there has not been an insolvency practitioner on the planet in the last forty years who has for an instant considered challenging the “single agreement” concept, which is not difficult to articulate — all our swaps net down to a single exposure — right? Yet, so ghastly are the dread phantoms that might alight upon the head of anyone foolish enough to ask that plainly stupid question — and so comfortable are the incomes of those brave thousands engaged in the annual harvest of prophylactic opinions giving it a sensible answer it barely deserves — that the industry tolerates a multi-million dollar annual expenditure without a second thought.

By contrast, a confidentiality agreement is part of the traditional pre-trade appendage-measuring ritual of the pea-cocks and pea-hens of finance. You have to do this; NDAs are meant to look fierce, but no-one is ever seriously hurt by them, and nor does anyone achieve much of lasting value out of them either. They’re a comfy part of the cosmic pantomime that is a career in financial services.

Even so, the abstract legal points of an NDA can be intricate — the world is awash with NDA templates riddled with schoolboy errors — though, since nothing of any commercial moment has ever depended on an NDA, the howlers persist: the people — and machines — engaged to process them need no great acumen, so we should not expect anything else.

Thus, NDAs — even for secret-squirrel event-driven family office types — rarely get past 5 or 6 pages, and are generally cleared in days. If you get stuck on one for more than a week, it will be some other problem the business guys don’t want to face that they are blaming on the NDA.

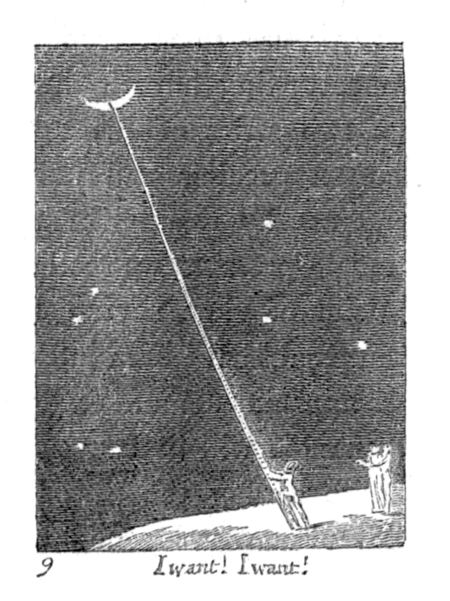

So there are local maxima and minima at play. An NDA, however important, complicated, and regardless of what fanciful things you bolt onto it (exclusivity, non-solicitation, restraint of trade, punitive damages and so on) may generate a few thousand pounds in billings, but even that is pushing beyond sensible expectation. With a syndicated bond issue, on the other hand, you can write a ticket to the moon.

This is why most magic circle law firms do not have “confidentiality departments” as such — everyone muddles along as best they can — but devote entire floors to debt capital markets.

Worked example

Take a USD500m loan. Even 0.05% of the deal value — as mere 5 basis points — is USD250,000. Is it any wonder the service economy is in such rude health? Who wouldn’t pay that to make sure nothing went wrong on half a yard of debt finance?

But even at USD500 an hour, that is five full working weeks of a legal eagle’s time:[3] it really wouldn’t do if all that was required was to top-and-tail the term-sheet with boilerplate and bang out an enforceability opinion. Nor would there be much prospect of stopping clients going to some other guy down the road who will do the job in a day and send a bill for a £500.

So — well, have a butcher’s at this this 370-page beauty and allow me to rest my case on it, since it plainly wouldn’t fit in it. Quarter of a mill well spent.[4]

See also

References

- ↑ “I have made this longer than usual because I have not had time to make it shorter.”

- ↑ For example, the patent applied for “MaJoR” Multi-Jurisdiction Repackaging Programme, which for a brief beautiful moment revolutionised the repack world, but inexplicably fell out of favour, to be replaced by earlier, crappier structures. Go figure.

- ↑ At 40 hours per week. Yes, we know that nowadays a transatlantic lawyer can expect to recover more billable hours per week than there actually are in the week, but we are assuming traditional laws of spacetime apply.

- ↑ We have NO idea how much the legal fees on this were, and it may be wildly defamatory to imply it was that much. Of course it could have been more.