Cost-value threshold

Cost-value threshold

(“CVT”) /kɒst-ˈvæljuː ˈθrɛʃˌhəʊld/ (n.)

|

The Human Resources military-industrial complex

|

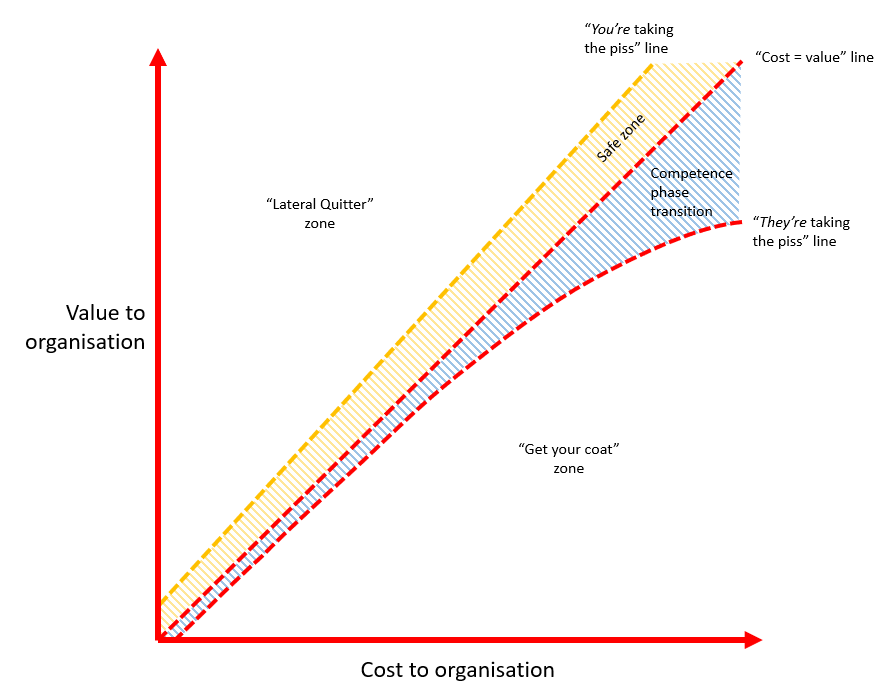

Human resources science: The point in an organisation where the value an employee, or capital item, provides, exactly equals its cost. Quality being relative to cost, good staff sit above this line; poor ones below it.

The “CVT” isn’t scientific. It is very, very hard to quantify the “value” of non-revenue-generating staff. In this day and age, that is most of us. I mean them.

And nor is one’s value over time necessarily stable. Some of us get better, some get worse. Contributions wax and wane. It is hard to know why.

Modernist ideology suggests one should keep all staff as close to the CVT as one can. To those who over-contribute, one should pay more to bring them into line; to those who come up short, one should pay less.

But practical challenges (namely, understanding what these people actually do, let alone how valuable it is), human frailty, market conventions, labour laws and so on means this won’t happen.

You can’t just pay employees less. Getting rid of them is expensive and risky. Coaching or managing dull workers to better performance requires talent your human resources department, being comprised of exactly that kind of worker, is certain not to have. And paying good performers more just because they deserve it strikes against basic tenets of modern human capital management.

There is, therefore, a penumbra: a warm “safe zone” above the CVT, where over-delivering employees can sit happily until their worth has drifted so far into the ionosphere that they are finally bid away, and a cooler, larger “competence phase transition” space below it where marginally net-negative staff can sit, for years, safely plodding along, not really helping, but also without great risk of prejudice, even when a reduction in force comes along.

Such inaction, however well intended, creates mediocrity drift.