Lateral quitter

|

The Human Resources military-industrial complex

|

“Our people are our most precious resource.”

- — oddly disingenuous slogans of HR: an occasional series

Lateral quitter

ˈlætərəl ˈkwɪtə (n.)

One who voluntarily leaves your organisation to work somewhere else. A greatly unexamined constituency.

Lateral quitters are good staff, QED

General a priori proposition: lateral quitters are good employees: ones you don’t want to leave, who add value. At least, they will be if HR is doing a passable job — Spartan if — because if so, poor staff won’t be leaving of their own free will.

Commercial firms are not charities for the intellectually vulnerable.[1] They should actively exit employees who are not performing to expectation. They should care, a lot, about looking after employees who are.

Maxim: Professional employment should not be a hostage situation. Either way.

The wilful blindness of management

Management will steadfastly deny any lateral quitter is missed. The trend towards “exit interview by chatbot” — if they bother with one at all — suggests corporations systematically undervalue the people they are losing.

HR departments everywhere seem gripped by the conviction that having employees at all is a matter for regret. Convinced that robots, chatbots, offshoring, or outsourcing, are better options, the HR military-industrial complex makes scant effort to discourage, impede or even identify those thinking of leaving, let alone asking those who do what their motivations were.

Now: if staff are such a waste of time, why go to the trouble of hiring them at all?

On the premise that all staff bring some value and, unless your approach to hiring is properly catastrophic, a good half bring more than they cost, lateral quitting is, broadly, a negative-sum game. That is, a game businesses should try not to play.

If you must view your staff as capital, then look at it this way: sell underperforming assets, by all means. Don’t let performing assets walk out the door.

So, some curiosity amongst the good people of human resources might be in order, for no other reason than to generate juicy metrics.

The data-richness of resignation

The JC finds inflated expectations of aggregated data tiresome — necessarily dead and backward-looking as data are — but even they have some worth when the questions asked are themselves historical.

So:

What percentage of staff chose to leave? In what departments? After how long? At what seniority? From which departments? Where to? Why?

This kind of data might suggest answers to the question: what does the firm do, or permit, that drives good people away?

Who are the poor managers? Where are the dreary departments? Which level is least proportionately rewarded? Answering questions like these can, in a small way, inform future behaviour: do more of this, and less of that.

It also turns the competency spotlight on an area where, internally, it is rarely pointed: management.

The exit interview is a unique chance to gather information staff are otherwise strongly disinclined to give you. Strictures of chain of command and conventions of corporate obsequy mean continuing staff — those with half a brain, at any rate — won’t usually tell you what they really think.

What pissed you off about working here? Who were the shittiest managers? What was the biggest drag?

But free, for the first and last time, of those chilling effects of free speech, they might just tell you in an exit interview.

Why not at least ask?

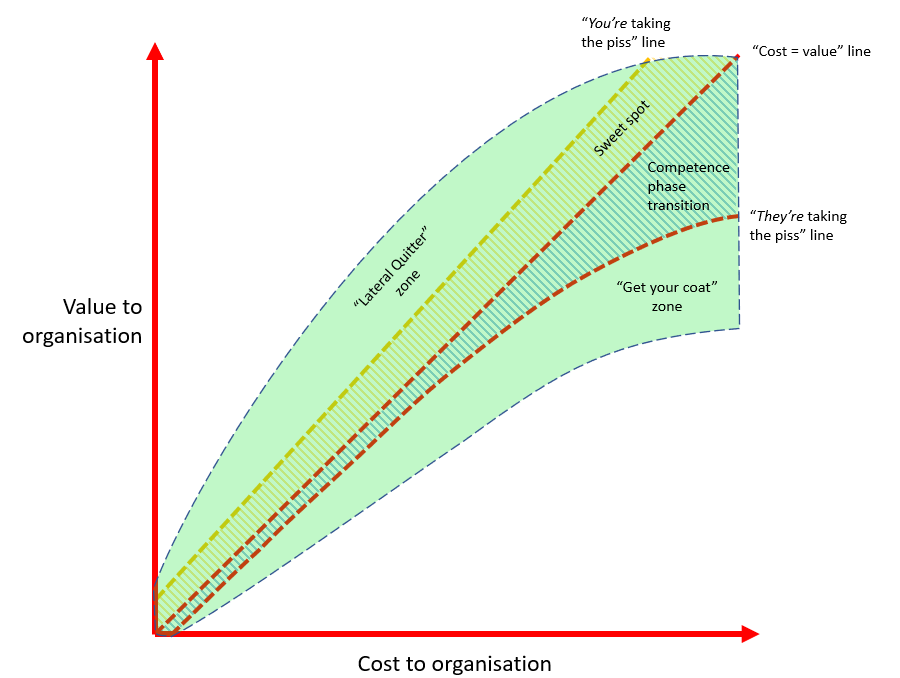

The competence phase transition

One cannot be binary about good and bad staff. There is a “bid/ask spread” between staff you genuinely value and those you would not mind never seeing again.

This we call the “competence phase transition”. It is a sort of purgatorial state, occupied by earnest plodders who don’t quite earn their keep but do no real harm, such that no-one can summon the bureaucratic energy to whack them, but nor would anyone wrong hands if they did decide to push off.

For the most part the “phase transition” is a stable state: staff of tepid bearing can comfortably inhabit it for decades: the JC speaks from happy experience. Every now and then, one may have a rush of blood to the head and throw in the towel — often at times of mass exuberance: you know, dotcom booms, crypto mania, that kind of thing — when in a fit of uncharacteristic madness, they vanish into fly-by-night stablecoin start-ups and legaltech ventures, only to reappear when chipped out of the fossil record of one of those mass extinctions that the financial services industry undergoes every decade or so.

Godspeed, all our friends in operation roles at Cryptöagle and Lexrifyly right now, by the way: hope it’s as fun as it looks while it lasts.

Mediocrity drift

Anyway. Being smart, lateral leavers tend to know they are better employees and be the proactive and energetic type who will do something about it.

Those plodders who provide an undervalue, by contrast, are unlikely to do anything about it — if they are smart — and even the dumb ones who try won’t be able to.

There is a negative feedback loop here, therefore. If all people you hire have an equal chance of working out well — their relative competence is evenly distributed — and those who outperform are likely to quit while those who disappoint are likely to stay, over time, the competency of your workforce will skew mediocre.

We call this “mediocrity drift”.

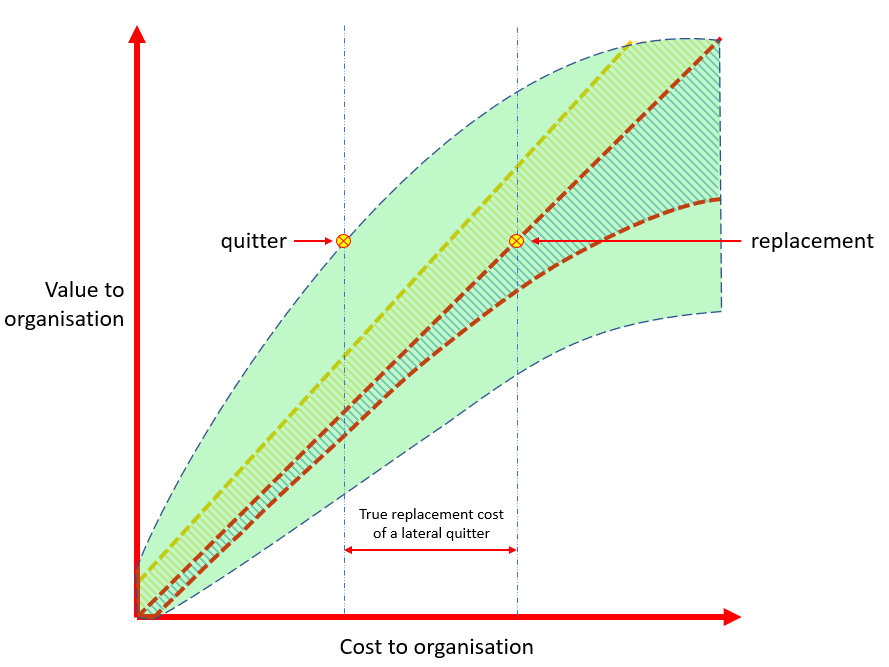

Outperforming quitters will be replaced — at necessarily greater cost, ceteris paribus, because the one and only time you are obliged to mark to market is when you hire — by those having no institutional knowledge, no internal network, and even controlling for that, only an “evens” chance of working out well.

The loyalty discount

“But we will reward the best staff with better pay and progression” will come the objection. While it may be true in a limited sense — you’d need planetary-scale density not to prefer good performers over bad ones, though this won’t stop HR trying — relative performance to each other — is not the measure that matters. It’s not a measure that even makes sense. What matters is net outcome: what do you get out of an employee, compared to what you put in.

The problem, of course, is that beyond revenue generating roles, and especially for risk management and control staff it is really hard to know. How do you measure legal value?[2] How do you count the dogs that don’t bark in the night-time?

HR’s stock answer is not to try. Instead, focus on what you do know — the spread of salaries across grades — and to focus on regularising that. Insist on fitting staff, to a model of relative performance against each other — the dreaded “curve”.[3]

This has all kinds of unwanted upshots, not least of which is instilling fear and loathing within a team which is meant to be collaborating. If you get to be the A-grade performer, then I can’t be. By HR diktat, a team of outperformers cannot exist.

To this end, HR will have ironclad compensation bands, based not on any assessment of individual quality (because how could HR, of all functions, possibly know?) but by some opaque “benchmarking” operation carried out by consultants “gathering data” from industry peers. However good an individual is, she will be forever pegged within her bands.

Where exactly this data comes from, no-one will say. Even if the consultants don’t just make it up out of whole cloth — Spartan if — it will have been volunteered by other HR departments. Now think about the interests at play here. If you were the highest payer on the street — therefore having a natural advantage over your peers in the lateral hire market — wouldn’t you want to keep quiet about that? Wouldn’t you be inclined to undercook the data you submitted to benchmark surveys? Would you weed out, for example, the lateral quitters who weren’t there at year end?

But come on JC: surely, regulated institutions wouldn’t knowingly skew important market data to suit their own financial interests, would they?

Once they have successfully “benchmarked” their salary bands against this phantom market, HR’s main concern will be not setting a precedent. Your manager will shake his head mournfully and say, “my hands are tied.” There will be overlaid volatility limits: no individual can move more than ~ percentage of last year’s pay. Note the necessary compressing effect these limits will have through time.

See also

References

- ↑ Though, some forget this. A large financial services institution recently displayed in its internal branding: “We are proud of our diversity policy. We hire regardless of physical or mental ability.”

- ↑ Divers essays on legal value, bullshit jobs and so on, refer.

- ↑ how do you use data measure the relative worth of a football team? Does the striker who runs 10km, scores a goal a game better than the goalie who covers 400m and scores none. Jaap Stamp example.