Clabby conversation

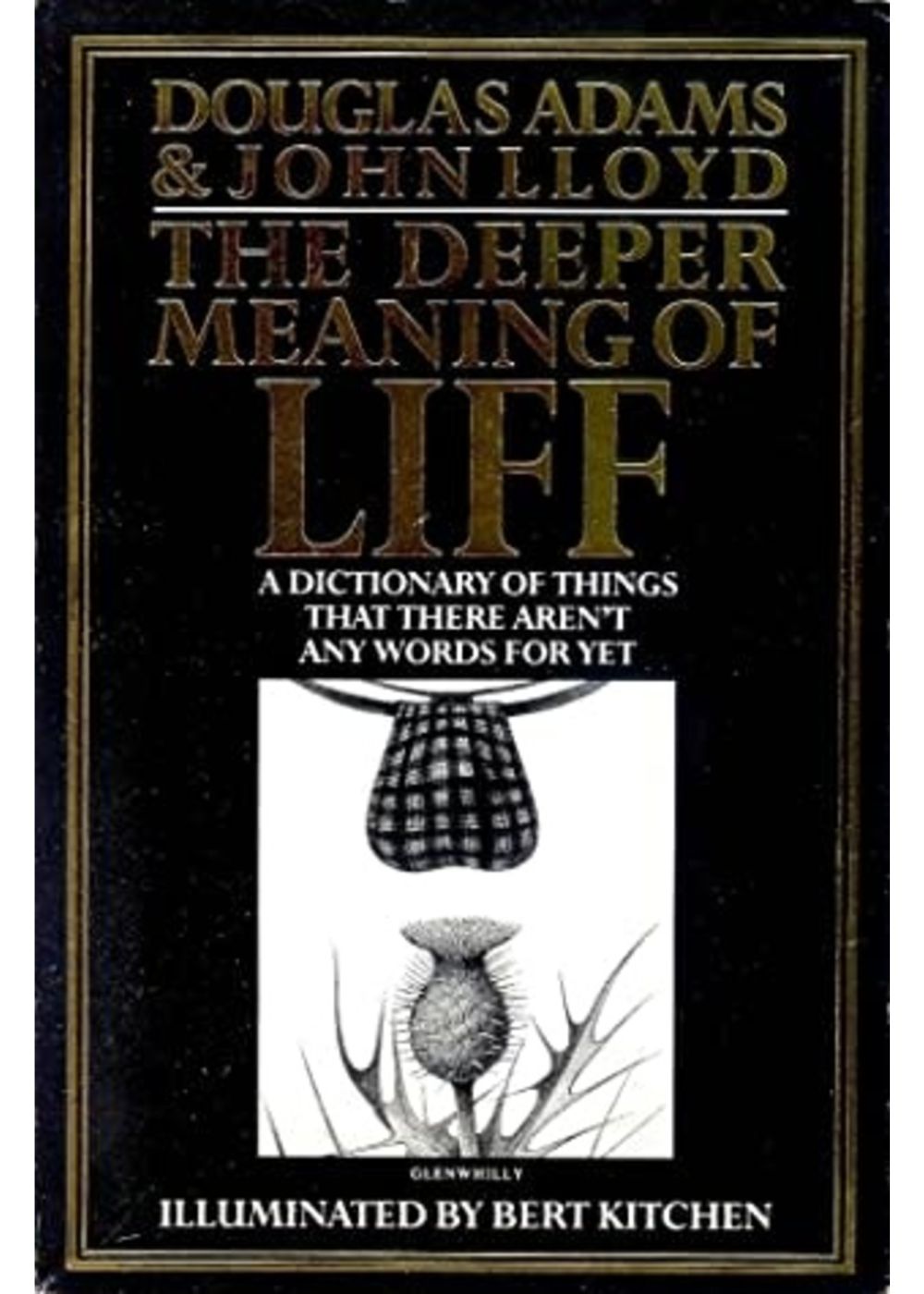

In Douglas Adams and John LLoyd’s excellent volume of lavatory wisdom, The Deeper Meaning of Liff — one of the many formative texts of the young JC’s education designed for consumption while on the throne — the learned authors define a “clabby” conversation as follows:

|

Office anthropology™

|

Clabby

/ˈklæbi/ (adj.)

A “clabby” conversation is one stuck up by a commissionaire or cleaning lady in order to avoid any further actual work. The opening gambit is usually designed to provoke the maximum confusion, and therefore the longest possible clabby conversation. It is vitally important to learn the correct, or “clixby” [“Politely rude. Briskly vague. Firmly uninformative.”] responses to a clabby gambit, and not to get trapped by a “ditherington” [“Sudden access to panic experienced by one who realises that he is being drawn inexorably into a clabby conversion, i.e., one he has no hope of enjoying, benefiting from or understanding.”] For instance, if confronted with a clabby gambit such as, “Oh, Mr. Smith, I didn’t know you’d had your leg off,” the ditherington response is, “I haven’t ...” whereas the clixby is, “good”.

The financial markets have their clabby gambits, and they usually emanate from counsel on a bond deal. This is not, despite appearances, egregious timesheet padding — I mean, it is, but not wilful — but just sheer force of habit: hundreds of years of dusty precedent weigh down on these poor lambs as they toil away on their trust deeds by candlelight, interlacing them with fripperous semantic aerations. The plainer ones are prefaced with homely platitudes: “for the avoidance of doubt”, “without limitation”, “notwithstanding anything to the contrary hereinbefore contained” — and such doggerel — but not always.

But here the clixby will do you no good, and you are forced into the ditherington gambit — pushing back on this pish — lest your contract collapses under the weight of its aeration some years hence.