Antitrust

Antitrust

/ˌæntɪˈtrʌst/ (n.)

It is through the offices of antitrust law that your plan to meet your buddy from Morgan Stanley for lunch, attend an industry round-table about Phase 5 Margin protocols will send your compliance department into high orbit. It is the legal eagle’s worst nightmare — that an innocent conversation about something sensible will see you both sent to jail.

Financial concepts my neighbour Phil was asking about when I borrowed his mower. Index: Click ᐅ to expand:

|

This is normally harmless nest-feathering of course, and simply allows parasitic law firms to nuzzle away at the collective arteries of the financial system in how they write netting opinions unbothered by earnest attempts to force them into some kind of consistency, but occasionally, as in the Archegos situation, the paranoid fear of one kind of opprobrium — being told off for collaborating in an anticompetitive way —can lead to the very real prospect of another — losing, between you, 10 billion dollars.

Calling Antitrust: come in, Antitrust

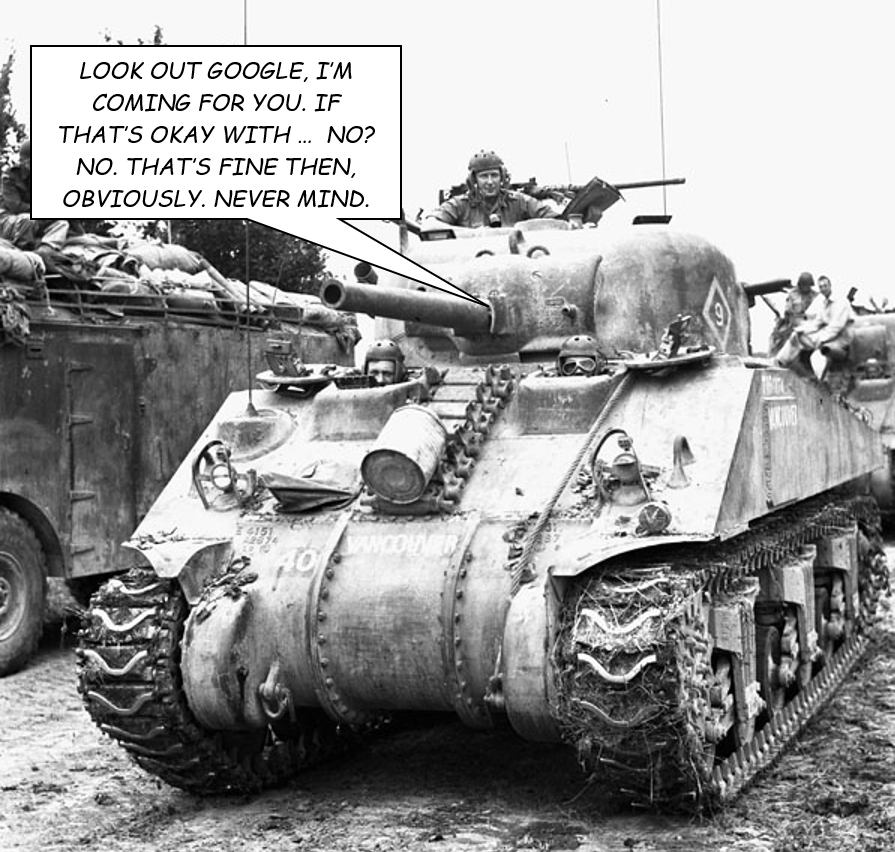

But here’s the funny thing. We fear the shadow of the antitrust reaper — and the odd careless executive might get thrown in jail for some small collusion — but on the grand scale, in terms of policing the basic thing antitrust is meant to stop — businesses acquiring and then exploiting dominant positions in the market — the antitrust authorities are absent without official leave.

Consider: the Sherman Act led, eventually, to the splitting up of Standard Oil, American Tobacco; United States Steel; Aluminum Company of America; International Harvester; National Cash Register; Westinghouse; General Electric; Kodak; Dupont; Union Pacific railroad; and Southern Pacific railroad and finally the Bell telephone system.

Few of these businesses had the sort of reach and dominance of Alphabet, Amazon, Facebook, Apple, Meta, yet we hear little from the regulators — some noise from the EU, almost none from the Americans.

Those in the know will say, “well, you see, it is all about whether the customer is hurt”.

Standard Oil gouged working class stiffs with its prices at the pump. But do you see the retail customers complaining about Apple, Google and Amazon? Facebook is free, for crying out loud!

This is, we think, to apply a narrow lens. The question here is about the orderly operation of markets, and a key component of that is scale.

The fatal flaw in ultra-free market capitalism — is its predication on perfect information and perfect opportunity to compete, which implies none of the participants have a material, inherent, advantage over the others. Scale gives exactly such a material, inherent advantage. Therefore a “perfect free market environment” is not a stable equilibrium. As it operates, the more successful participants will get bigger, and acquire economies of scale. As they get bigger, they become more effective competitors, meaning they win even more market share, meaning they get bigger still.

Now, until about 1980, there were limits to the economy of scale: there is a point where the internal organisation itself gets so unwieldy, and irrevocably committed to a single business model, that it can’t innovate, or react to smaller competitors who do. You create supply chains, branch networks, warehouses, and so on. These have a drag on your profitability, and are increasingly difficult to change should the market change. So the “scale effect” wears off and ultimately can go negative: the bigger you are the worse a competitor you are.

Then things changed

But starting in the 1980s two things happened to change this.

Firstly, the privatisation ideology took hold of the private sector: In the same way governments were getting out of non-core activities like running railway lines and coal mines, so did corporates get out of what they supposed to be non-core activities like manufacturing parts (and, er, negotiating finance contracts): whole divisions were outsourced, off-shored, spun off, de-merged, or just shut down, giving the “core business” back a lot of flexibility it had lost. If you own your production line, it is an expensive exercise to junk it if it no longer makes sense. If you have outsourced it, its’ a cinch: just terminate the contract and walk away.

Secondly, the internet arrived. Suddenly, “old economy” businesses found they could cheaply connect with their customers, suppliers and markets. They no-longer needed their huge distribution network infrastructure to reach their clients. It got a lot easier to communicate internally. Suddenly size was less of a burden — and if it became one, it became much, much easier to outsource.

In knowledge industries, operations, infrastructure, human resources, contract negotiators, customer services representatives all found themselves suddenly jettisoned to third-party call centres in places like Belfast, Glasgow, Bucharest and Bangalore. More of the inhibitors of economy of scale were went away.

Even so, some sleeping giants missed the boat and quickly lost out to scrappy start-ups like Amazon: Barnes & Noble, Tower, Sears & Roebuck, even IBM. But suddenly the startups themselves were behemoths, their lack of infrastructure meant they could beat out the giants.

Suddenly, scale was much less of a limiting factor, because so much of it could be achieved with software.

A similar thing was happening in banking. Banks started scaling back branches, and reaching customers electronically. Previously, banks had grown (like Citi) through acquisition.

Antitrust is not the only game in town

Seeing antitrust as purely a consumer satisfaction tool is, we think, short-sighted.

Ensuring market stability, vouchsafing a robust market, fostering innovation. These are things consumers don’t realise they want until they are not there (and it will never know what innovation it hasn’t missed. Now not just the regulatory barrier to entry but a scale one. As we rolled into the 2000s we became aware of a bigger problem: too big to fail and systemically important financial institution: banks that are so big, and so interconnected, that if they collapse they can trigger Armageddon. Most investment banks are well and truly past that point.