Boilerplate

Boilerplate

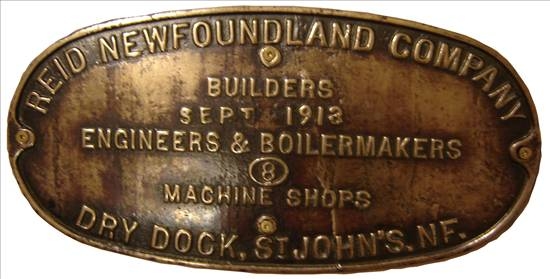

/ˈbɔɪləpleɪt/ (n.)

|

Boilerplate Anatomy™

|

Since brevity is the soul of wit,

And boilerplate the crutch of wretched tedium

I will be brief, where Triago, in all his trite facility, cannot.

A work-creation scheme for our learned friends.

Legal eagles love the idea that the standard, tedious terms that make up the lion’s share of commercial legal discourse are special.

Then again, we all — not just lawyers — like to believe our own domain is sacred: that we are privy to something critical; dangerous; delicate — arcane learning that, should it fall into unskilled hands, may wreak great ill upon the bystanding world.

Make way: I’m a doctor.

But our dark secret: much of what we do, to get to those subliminal moments of rarefied artistry, we do on autopilot. To win Le Mans, first keep the engine tuned, the tank filled and the tyres pumped up. Then drive like Stirling Moss.

Boilerplate is the spark-plugs and fan belts of legal machine: workaday engineering that makes stuff go. It is system 1: fast thinking: coded, compiled, engineered into the foundation. What we want from it is reliability. it cannot win us the race, but it can help stop us losing it, by working dependably without breaking down.

“Working” means “going in easily” — without argument — and “being commonly understood”; at the limit, being able to withstand scrutiny before the King’s Bench Division, though categorically not being written for a judge.

That quality is not intrinsic to the boilerplate itself, but is a function of what the community thinks it means. There is an emergent strength in consensus: if everyone uses it, it is more effective, by itself, regardless of the cleverness of its engineering. Law is a sociological phenomenon, first and foremost. Everyone knows that “in the public domain” means “public”. No-one would ever take that point.[1] Not, at least, as far as court.

We should therefore regard boilerplate as a public resource. A utility. Not special sauce, not an asset, not “part of the magic”. We should not extract rent from it. Lawyers don’t help anyone, or nourish their own souls, by acing boilerplate.

So, folks, let it go. Set your boilerplate free.

The quotidian is a utility, not an asset.

Boilerplate and the cocktail napkin

I define “legal boilerplate” expansively, and that is to say “anything that didn’t make it onto the cocktail napkin”. Those terms, thrashed out over Martinis and peanuts in some ill-lit bar in a skanky part of town at three in the morning, the commandments on the stone tablet that Moses fished out of a burning bush in the Red Sea[2] — that’s the deal, and we legal eagles have little to say about it, assuming it doesn’t actually break the law.[3]

The remainder, be it the classic boilerplate that fills our anatomy, or the “legally vital protections for our client” — the events of default, the termination events, the close-out netting provisions, the indemnities, the security waterfalls — it is all, in this wider sense, boilerplate: it is there simply to avoid doubt.

Boilerplate within the boilerplate

There are degrees of boilerplate. Legal eagles will get het up about indemnities, default events and close out rights, and swear blind that these aren’t just boilerplate. (They are.) To be sure, they excite animal passions — at least, amongst credit officers and lawyers — in a way that representations and warranties, covenants, notices, governing law, counterparts, entire agreement, amendments, process agent appointments, Contracts (Rights of Third Parties) Act 1999 exclusions and so forth really don’t.

The buried risk of boilerplate

So, all that pointless guff down the back of the agreement that no one, least of all the client, reads, that makes a cocktail napkin complicated — any of it can swing around and bite you when you least expect it. Especially if, as you won’t be, no one is monitoring for compliance with the boilerplate in the first place.

If we take it that a legal provision, however standard, does something — that is to say, it alters the state of affairs between the merchants from the one that would prevail if nothing were said — and boilerplate must do: for why else say it? — and since boilerplate therefore necessarily reallocates risk away from its “natural” destination — then the question atop of a negotiator’s mind when preparing a draft ought to be, “is such a perversion of the natural order of things justified, and if so, why? How has the common law managed to get standard things so badly wrong?”

For much of the litigation over boilerplate — and there is a disheartening amount if it — boils down to a fight between one side arguing for a commonsense commercial outcome based on the essence of the cocktail napkin — that is, the understanding that passed between the merchants during their commercial discussions — and the other side, seeking to make out a freakishly distorted outcome with no equitable rationale but that is vouchsafed by creative application of boilerplate terms to which no one paid the blindest bit of attention when the contract was being negotiated.

You may call this a jaundiced view, but really, if boilerplate is designed only to reinforce the settled position of the common law, what does it achieve, other than heft?

See also

- Mark-up the last deal

- OneNDA — kind of like the little Hobbits’ journey to mount doom

- Flannel

References

- ↑ The doyen of drafting is not no-one, obviously.

- ↑ Choose your own metaphor, okay?

- ↑ In the case of the ten commandments, it is the law. We’ll just fill a couple of testaments and countless apocrypha amplifying and interpreting it, is all. So: ten commandments: the deal. The Bible, the Torah, the apocrypha and a couple of thousand years of Judeo-Christian intellectual hereitage: boilerplate. P.S. yes, I know the commandments didn’t come from a burning bush in the Red Sea.