Innovation paradox

|

JC pontificates about technology

An occasional series. This article is a 20-year meditation following a conversation had, in 1999, with C.E.M.C., for whose guidance I offer huge thanks and profound respect.

|

The Jolly Contrarian's contrarian advice : to increase efficiency, seek to remove technology from the workplace.

Why do reg tech solutions promise so much but deliver so little? This is the Innovation paradox. Is it a paradox, though?

"We don't pay lawyers to type, son"

Classic example: computers and the law. In 1975, when you wanted to edit a legal contract during the negotiation that would mean retyping the entire page. Hence, legal comments in a negotiation were necessarily bounded by the effort and time of recreating the document. There was an art to saying something once, clearly and precisely. Since editing was wasteful exercise, superficial amendment was not, for the avoidance of doubt, the apparently[1] costless frippery it is today.

Things weren’t so bad in 1975. There was a natural limit on legal wrangling. The physical cost partly negated the anal paradox.

By 1995 lawyers had computers on their desks, and the traditional refrain[2] "we don't pay lawyers to type, son" was beginning to lose its force.

Suddenly, it was easy to re-spawn documents, to tweak clauses, shove in riders — to futz around with words. Generating and sending documents was free and instantaneous. Negotiations quickly became convoluted and elongated. You argued about trifles because you could. It also lowered the bar: certain classes of agreement which previously could not justify their own existence, let alone legal negotiation, could now be thrashed out and argued about. Far from accelerating negotiations and enhancing productivity this gave lawyers free licence to indulge their yen for pedantry.

I have no data for this — where would you get them? — but I am certain the number, length and textual density of legal contracts exploded after 1990.

Yet, yet yet: many painful artefacts of the analogue era — the gremlins and hair-balls you would expect technology to remove — persist to this day. We still have side letters. We still have separate amendment agreements. We still, solemnly, write: “this page is intentionally left blank”. We still say “this clause is reserved”, as if we haven’t noticed Microsoft Word has an automatic numbering system. Not only has regtech failed to remove expected complexities, it has created entirely new ones.

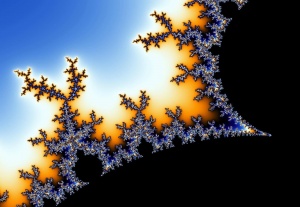

Why is this? It is a function of the incentives at play. Lawyers and negotiators are remunerated by time taken. They are rewarded for the complexity and sophistication of their analysis. Lawyers don’t want to simplify. Lawyers don’t want to truncate. That isn’t in their nature. It is contrary to their nature. This is not what lawyers will use technology for. Lawyers will use technology to find new complexities. To eliminate further risks. To descend closer to the fractal shore of risk that it is their sacred quest to police. But that shore is fractal. However close you get, the risks remain.

Technology has brilliantly enabled lawyers to showcase the sophistication and complexity of their syntax. In a nutshell: We lawyers use technology to indulge ourselves.[3]

See also

References

- ↑ But not actually. See: Waste.

- ↑ I actually had an office manager say this to me, as a young attorney. True story

- ↑ There is a serious point here for people (like me) who argue that technology implementations should be driven as far as possible by users at the coalface. And that is to bear in mind that the interests of users at the coalface are not necessarily aligned with those of the organisation for which they are working.