Virtue signalling

A form of preaching to the choir, only with added moralising, virtue-signalling is making a statement that looks brave but is not, predominantly to garner approval. The best way of doing that is to make your “brave” stance to an audience of credulous libtards whom you know will uniformly agree with it.

|

Social media are intrinsically excellent for virtue signaling, because it costs nothing to make a statement, and you can choose & filter your audience (or it chooses and filters you) based on pre-determined proclivities.

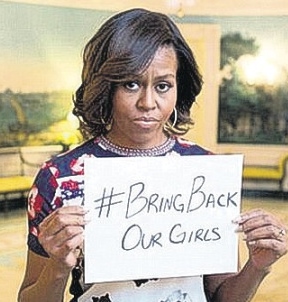

The cause célèbre of virtue signaling followed Boko Haram’s kidnapping of 276 girls from a Secondary School in Nigeria in 2o14. This was a categorically horrific act, to which most of the networked world responded, on Twitter, with the hashtag #BringBackOurGirls, often accompanied by a photo of individual (the most famous was Michelle Obama), moon faced, holding up the hashtag on a piece of paper. Everyone joined in. Easy, cheap, filling oneself with a sense of lofty righteousness and achieving precisely nothing.

The point isn’t to criticize the sentiment — what kind of monster[1] could do that? — but to ask what practical good it does? Would a worldwide crush of hashtags lead a religious fundamentalist to the error of his ways[2]? Or was that not really the point, but to visibly, righteously, show concern in a costless but bragadocious way?

Since virtue signalling namechecks politically correct issues du jour it a natural bullshit detector bypass - and where it doesn’t bypass the bullshit detector, it certainly mutes it. Calling out bullshit is over thing, calling out a virtue signalling bullshitter risks challenging the signal -which may indeed be bullshit, but that's not the point, is it?

Prime example: yogababble Adam Newman from WeWork. “At WeWork we don’t discriminate. We are going to build something. We are going to change the world for the better.”

See also

References

- ↑ Well, obviously a member of Boko Haram, of course. But you get the point.

- ↑ No, sayeth Wikipedia: “However, with limited action and success after initial protests in 2014, little has been accomplished through social 0/media regarding results. As of January 13, 2017, 195 of the 276 girls are still in captivity, close to three years after the kidnappings.”