Lateral quitter

Lateral quitter

ˈlætərəl ˈkwɪtə (n.)

One who voluntarily leaves your organisation to work somewhere else. A greatly unexamined constituency.

|

The Human Resources military-industrial complex

|

“Our people are our most precious resource.”

- — oddly disingenuous slogans of HR: an occasional series

The wilful blindness of management

Management will steadfastly deny any lateral quitter is missed. The trend towards “exit interview by chatbot” — if they bother with one at all — suggests corporations systematically undervalue the people they are losing.

HR departments everywhere seem gripped by the conviction that having employees at all is a matter for regret. Convinced that robots, or offshoring, or outsourcing, are better options, the HR military-industrial complex makes scant effort to discourage, impede or even identify those thinking of leaving, let alone asking those who do what their motivations were.

On the premise that all staff bring some value and, unless your approach to hiring is properly catastrophic, a good half bring more than they cost, lateral quitting is, broadly, a negative-sum game. That is, a game businesses should try not to play.

So, some curiosity amongst the good people of human resources might be in order, for no other reason than to generate juicy metrics.

The data-richness of resignation

The JC finds inflated expectations of aggregated data tiresome — necessarily dead and backward-looking as data are — but even they have some worth when the questions we are asking are themselves historical. So:

What percentage of staff are choosing to leave? In what departments? After how long? At what level? From which departments? Where to? Why?

This kind of data might suggest some answers to this question: what does the firm do, or permit, that drives good people away? Who are the poor managers? Where are the dreary departments? Which level is least proportionately rewarded? Answering questions like these can, in a small way, inform future behaviour: do more of this, and less of that.

So, the exit interview a unique chance to gather data staff are otherwise strongly disinclined to give you. Strictures of chain of command and general conventions of corporate obsequy mean wise staff won’t usually tell you what they really think. But free, for the first and last time, of those chilling effects, they might in an exit interview.

Why not at least ask?

Lateral quitters are good staff, QED

Lateral quitters tend to be good employees: ones you didn’t want to leave, who contributed more than they cost. They will be that, at any rate, if HR capability is working passably — Spartan if — because if so, you will have already thinned out the laggards. Right?

Maxim: Professional employment should not be a hostage situation. Either way.

The competence phase transition

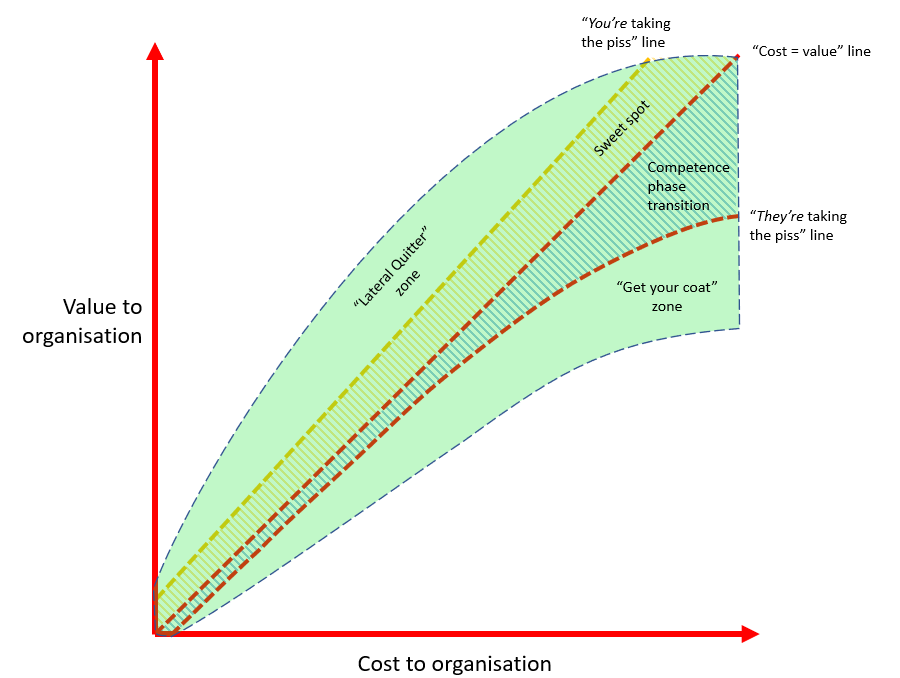

Now, it is true: there is a “bid/ask spread” between staff you genuinely value and those you would not mind never seeing again.

This we call the “competence phase transition”. It is a sort of purgatorial state, occupied by earnest plodders who don’t quite earn their keep but do no real harm, such that no-one can summon the bureaucratic energy to whack them, but nor would anyone wrong hands if they did decide to push off.

For the most part the “phase transition” is a stable state: staff of tepid bearing can comfortably inhabit it for decades: the JC speaks from happy experience. Every now and then, one may have a rush of blood to the head and throw in the towel — often at times of mass exuberance: you know, dotcom booms, crypto mania, that kind of thing — when in a fit of uncharacteristic madness, they vanish into fly-by-night stablecoin start-ups and legaltech ventures, only to reappear when chipped out of the fossil record of one of those mass extinctions that the financial services industry undergoes every decade or so.

Godspeed, all our friends in operation roles at Cryptöagle and Lexrifyly right now, by the way: hope it’s as fun as it looks while it lasts.

Mediocrity drift

Anyway. Being smart, lateral leavers tend to know they are your better employees and be the proactive and energetic type who will do something about it.

Those plodders who provide an undervalue, by contrast, are unlikely to do anything about it — if they are smart — and even the dumb ones who try won’t be able to.

There is a negative feedback loop here, therefore. If all people you hire have an equal chance of working out well — their relative competence is evenly distributed — and those who outperform are likely to quit while those who disappoint are likely to stay, over time, the competency of your workforce will skew mediocre.

We call this “mediocrity drift”.

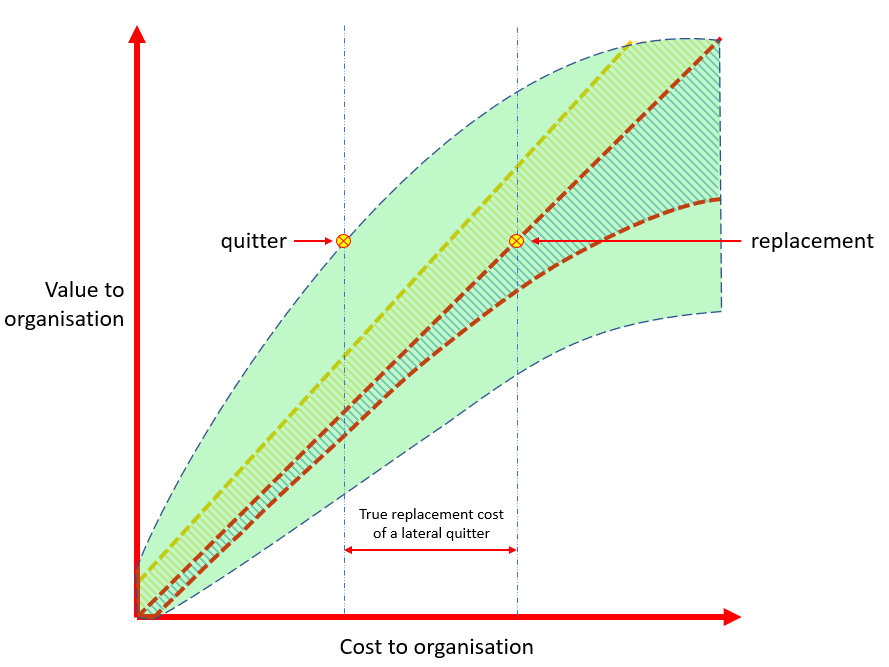

Outperforming quitters will be replaced — at necessarily greater cost, ceteris paribus, because the one and only time you are obliged to mark to market is when you hire — by those having no institutional knowledge, no internal network, and even controlling for that, only an “evens” chance of working out well.

The loyalty discount

“But the best staff will be rewarded with better pay and progression” will come the objection and while it may be true on its own relative terms — you would need density of a planetary scale not to systematically prefer good performers over bad ones, though this won’t stop HR trying — relative performance to each other — the dreaded “curve” — is not the measure that matters. It’s not a measure that even makes sense. What matters is net outcome: what do you get out of an employee, compared to what you put in.

The problem, of course, is that beyond revenue generating roles, and especially for risk management and control staff it is really hard to know.[1] How do you count the dogs that don’t bark in the night-time?

HR’s answer is not to try, but instead focus on what you do know — the spread of salaries across grades — and to focus on regularising that. One does so by fitting staff, based on a compulsory relative assessment, to that model.[2]

To this end, HR will have ironclad compensation bands, based not on any assessment of individual quality (because how could HR, of all functions, possibly know?) but by some opaque “benchmarking” operation carried out by consultants “gathering data” from industry peers. However good an individual is, she will be forever pegged within her bands.

Where exactly this data comes from, no-one will say. Even if the consultants don’t just make it up out of whole cloth — Spartan if — it will have been volunteered by other HR departments. Now think about the interests at play here. If you were the highest payer on the street — therefore having a natural advantage over your peers in the lateral hire market — wouldn’t you want to keep quiet about that? Wouldn’t you be inclined to undercook the data you submitted to benchmark surveys? Would you weed out, for example, the lateral quitters who weren’t there at year end?

But come on JC: surely, regulated institutions wouldn’t knowingly skew important market data to suit their own financial interests, would they?

Once they have successfully “benchmarked” their salary bands against this phantom market, HR’s main concern will be not setting a precedent. Your manager will shake his head mournfully and say, “my hands are tied.” There will be overlaid volatility limits: no individual can move more than ~ percentage of last year’s pay. Note the necessary compressing effect these limits will have through time.

Now you might be inclined to look at this and think, well, this is a fine state of affairs. By pruning the truly dismal and letting jumped-up and flighty go, we are nicely containing our costs within a tight range. This is depends on your not needing to replace them.

Indeed, in an organisation big enough to have a human resources department you probably don’t — or at least wouldn’t, if you could hang on to staff who were any good and get rid of the grifters. Parkinson’s law obtains.

But if all you have left are the plodders, do not expect them to take up the slack. You will need a replacement, and — unlike the person who just departed — you must per her her actual value. At this point you have categorically worsened your position.

Look after what you have

How to stop this? Well, for one thing, focus your attention on your employees who deserve it: the good performers.

Try to stop them leaving. Do this by figuring out why they are leaving. There may be complicated sociological explanations, but for most places it will take no towering intellectual insight to figure it out. In broad strokes it boils down to: money, progression, and quality of work.

Another way of looking at that continuum is this: you pay poor employees more than they are worth to you, and good employees, less than than they are worth, expect to have crappy employees.

See also

- ↑ Divers essays on legal value, bullshit jobs and so on, refer.

- ↑ how do you use data measure the relative worth of a football team? Does the striker who runs 10km, scores a goal a game better than the goalie who covers 400m and scores none. Jaap Stamp example.