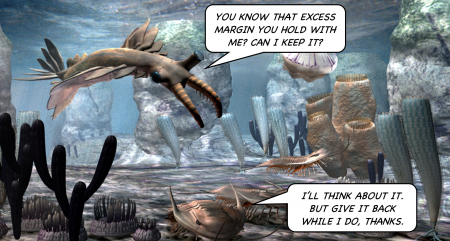

Burgess Shale

If the financial services industry is a grand experiment in the social evolution, then one of its infrequent shocks — LTCM, l’affaire Enron, the global financial crisis, the LIBOR scandal — are surely inflection points: quick, mass extinctions, punctuations to the normal equilibrium state through which the genetic adaptations of commerce make their stately way. We should watch them carefully, for we may see organisms, as they sink into the mud, going extinct in real time. These events are our Burgess Shales. They are a precious treasure-trove: the laying down before us of a fossil record, not of what went before, but what comes afterward, is illuminating.

|

|

The Burgess Shale is a fossil-bearing deposit exposed in the Canadian Rockies, famous for its exquisite fossils of soft-bodied organisms. It has given palaeontologists a huge amount of ecological information on animal communities during the end of the Cambrian Explosion.

“Punctuated equilibrium” is a theory of evolutionary biology proposing that once a species appears, its population will become stable and will show little evolutionary change for most of its history. The theory restricts significant evolutionary change to rare and geologically rapid events whereby one species splits into two distinct species, rather than one gradually transforming into another. It stands in contrast to the idea that evolution occurs gradually and uniformly, transforming whole lineages in a smooth, continuous fashion.

- —Wikipedia (adapted)

We have one before us in the shape of Archegos. We’ve written about it elsewhere, but there is one other aspect to consider: what the CS Report on Archegos is doing to the fragile psychologies in the executive suites of other institutions.

These executives will have read the report with a view to constructing their own unique, imaginative conclusions, from which they will draw lessons carefully wrangled so as to fling responsibility as far as such a thing can be flung from such an elevated position. Things thrown from the top of a hill tend to land further down it. Thus, as Sidney Dekker reminds us, in any industry beset by calamity, “operator error” is usually the first identified cause.[1]

External events fan these anxieties. A trade magazine[2] will publish some piece about what happened, who lost what, and how participants are now reacting. This must necessarily be based on utter speculation — one thing all bankers are is circumspect about what they tell media organisations — and will usually be a fantastical tissue of hyperbole, fiction and inexpert supposition: those learned, experienced and adept in the dark arts of derivatives pricing generally earn their crust actually pricing derivatives, not conjecturing about how other people do it. But this will not matter: the piece will spread like wildfire around the C-suites of the city. The executives will devour it, believing every word to be a gospel indictment of anyone and everyone for whom they are not responsible in the present chain of command.

“We must have the right to call margin immediately, eight times a day if need be, on immediate notice,” the senior executives will cry. “We must have covenants! Perhaps we should require our counterparts to monitor their own risk limits for us! They can close themselves out on our behalf! Yes! What has no one thought of this before! Make it so!”

These diktats will come from those lofty executives known to (and feared by) all throughout the organisation by their christian names. These men — most will be men — will know none of the minutiae, the operating parameters or, God forbid, commercial realities of the businesses at which they have suddenly waived their wands, but no matter: if the head of risk has mandated that jelly must be nailed to the ceiling, so it must.

Resistance is useless; practical objections — such as, “well, how the hell is that meant to work?” or “but we have no systems to monitor that”; “our most valuable (ergo risky) clients will never agree to it”; or “it would be practically impossible to run a margin process across the whole client portfolio more than once a day anyway, even if our systems were remotely capable of it” — will at best fall upon deaf ears, but are more likely to be regarded as a form of insurrection.

So will begin the hue and cry for something tangible, visible and fixable for people to do, so these grim happenings can be put away forever.

This needs to be something visible, formal and countable for the Steerco PowerPoints and the presentations to regulators, public statements and so on. The executives must be able to say, “before it was night, and now it is day. And this proves it.”

You can see how “we’re all being a bit more switched on from now on” doesn’t make for the most compelling press release in the world, after all. But overhauling systems is expensive, time consuming, difficult, and tends not to work, so this is where dear old legal comes into the frame.

“Could we maybe put something in the docs?” the head of risk will gingerly enquire. He will direct this enquiry not to the subject matter expert in the derivatives team, whom he will not know to exist, but to the General Counsel, who will “take an action” to get it done (he won’t know the SME in the derivatives team either).

And so, it shall be done: messages will be relayed down the chain, the last to hear will be our benighted derivatives SME, and by the time she gets wind of it, not only will it be far too late to beseech anyone to see sense, the deadline to make it so will have already expired, so she must do what she can, as quickly as she can, to report back up the chain to the management committee that it has been done, so someone important can tick a box and approve a press release.

Over the next 24 months, the documentation team will heroically battle away to get the new language in, but every major client will reject it, and after two years there will be exactly no examples of it in the agreement portfolio, though the negotiation throughput will be 25% slower as a result. This may lead to cost-cutting measures being imposed on the legal team — principally the derivatives SME, since she was the one that put in the language that caused all the bottlenecks in the first place.

And that, ladies and gentlemen, is how legal documents become so unwieldy, and why negotiating then is such a chore. In five years’ time another family office will blow up, and there will be exactly the same hue and cry, with exactly the same outcome. The chutzpah to think a problem significantly serious to cause a billion-dollar loss really comes down to a representation no-one thought to add to the thousands of pointless representations already encrusted in the document no-one looks at.

Perhaps, we venture, the problem is bigger than that. Perhaps that, in its way, is the problem. Perhaps we need a weightier response. A different approach; a re-think; perhaps a superficial gloss on the current status quo won’t do.

Perhaps, folks, it’s not about the docs.

See also

References

- ↑ Sidney Dekker’s The Field Guide to Human Error Investigations

- ↑ Generally defined as a funded-by-advertising publication read only by those in the industry on whom it bestows awards, and those who haven’t yet worked out how to unsubscribe from its spambot.