Seeing Like a State

Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed — James C. Scott

|

No battle — Tarutino, Borodino, or Austerlitz — takes place as those who planned it anticipated. That is an essential condition.

- —Tolstoy, War and Peace

This one goes to the top of JC’s 2020 lockdown re-reads. It was published in 1998, so it’s a bit late to get excited — but while it addresses the “high modernism” of modern government, the read-across to the capitalist market economy, and beyond that into the modern large corporate — are you reading, boss?[1] — shrieks from every page. These are profound ideas we all should recognise, but — being, well, citizens of a “prostrate civil society” — either we can’t or we won’t.

Seeing Like a State takes as its thesis how well-intended patrician governorship can, in specific circumstances, lead to utter disaster. While Scott’s examples are legion one could, and some do, criticise him for his anecdotal approach: he has curated examples that best fit his thesis, and it therefore suffers from confirmation bias. That may be true, but I don’t think it matters, for Scott’s thesis, when set out, is so familiar, so plausible and its exhortations so consistent with other theories in adjacent fields,[2] that it is hard to be bothered by a lack of empirical rigour. Data is not its value: its narrrative is its value. Scott is providing a counter-narrative to modern statist (and corporate) orthodoxy, and that in itself is valuable and enlightening.

In any case, bureaucratic disaster is not inevitable, but the same four conditions are present wherever we find it: a will to bend nature, and society, to the administrator’s agenda; a “high modernist” ideology believing that all problems can be anticipated and solved ahead of time; an authoritarian state with machinery to impose its ideological vision; and a subjugated citizenry (or staff) without the means (or inclination) to resist the machinery of the administrator.

All of these qualities feature in the modern multinational corporation. If you are interested in how not to run one, Seeing Like a State is worth a close read.

Legibility: the administrative ordering of nature and society

Any government must be able to “read” and thus “get a handle on” — hence, “make legible” — and so administrate the vast sprawling detail and myriad of interconnections between its citizens, lands and resources. It does this by, in its “statey” way, narratising a bafflingly complex system into a thin, idealistic model: it assigns its citizens permanent identities (in the middle ages, literally, by giving them surnames: now, identity cards and the chips that are shortly to be implanted in our foreheads); it decrees standard weights and measures for all times and places (we may have proceeded by local customs and conventions;[3] commissions cadastral surveys of the land so it can collect taxes; it records land holdings, registers births, deaths and marriages, imposes conventions of language and legal discourse designs cities and transport networks: in effect, to create a standard grid that could be measured, monitored and understood from the bird’s eye view of city hall. A population that legible is manipulable.

This cost of this legibility is abridgement: it represents only the slice of society that interests the administrator, which would be harmless enough those measures did not in turn permanently impact how citizens interact with each other and their environment. So, society came to be remade to suit the administrator. Thus, a reflexive feedback loop.

Scott is persuasive that we lose something critical when we simplify in our yen for clear description, which state officials cannot but do. Trying to covert local customs — “a living, negotiated tissue of practices which are continually being adapted to new ecological and social circumstances — including, of course, power relations” — to unalterable laws loses subtlety and micro-adjustments that these customs are continually experiencing.

In other words, you lose something special when you atomise a complex system. Emergent properties vanish. It is a poorer, less productive thing.

High modernist ideology

When your yen to regularise society is accompanied by the “muscle-bound” self-confidence that you can expand production, better satisfy human needs and master nature (including human nature) and centrally configure social order “commensurate with the scientific understanding of natural laws”. It translates to a rational, ordered, geometric (hence “legible”) view of the word and depends on central state vision to bring about big projects. Now those infinitesimal interconnections and illegible relations are not just invisible to the state programme but inimical to it. Natural forests are replaced with grid-planted Norfolk pines and swathes of the unwanted ecosystem are rejected because they don’t fit the model. But they can play valuable and vital roles in the ecosystem. The simplistic deterministic belief that they are not necessary will eventually come back to haunt you. “Nature,” as Dr. Ian Malcolm put it in Jurassic Park, “finds a way”.

The high modernist believes the future is somehow solvable and certain, and the certainty of that better future justifies the disruption and short-term adverse side-effects of putting in place a grand plan to get there. The counterpoint to this approach is the iterative, ground-up organic adjustment of people on the ground, using their judgment and experience to best improve the lot as they personally see it. As long as you have the right people on the ground, this is both far more effective for society, and far scarier for administrators: they have less control over progress, less sight of it, (therefore) less to do, and a harder job justifying the rent they extract (in a government, this is called a “tax”; in a corporation, it is executive compensation) for providing their “vital” administration.[4]

Once the desire for comprehensive urban planning is established, the logic of uniformity and regimentation is well nigh inexorable. Cost effectiveness contributes to this tendency. Every concession to diversity is likely to entail an increase in time and budgetary cost.

Another cost of the high modernist ideology that seeks to regularise and unitise is diversity in the things so regularised.

That diversity and inclusion is the cause célèbre du jour, in the public and private sectors, hardly falsifies this observation. It just sharpens the irony, since the typical approach to delivering diversity chimes with this desire for narratising legibility and high-modernism.

Diversity ought, you’d think, to be hard to pin down, its manifestations being naturally — well — diverse. But to get a handle on diversity in their populations, organisations must make it legible. They do this by defining “diversity” in a strikingly limited way, then seeking to gather data from their staff on that limited metric, so that they can propagate statistics about their changing diversity. Thus, diversity is formalised, homogenised, parameterised and regularised, and no attention is paid to the product and output of diversity at all. As long as we look diverse, and talk tike we’re diverse, but everyone fits neatly into one of the five boxes we have prescribed for them, in the right proportions, we have achieved our goal. Sounds a bit like an Aldous Huxley novel, doesn’t it? Feels a bit like one too.

An authoritarian state and prostrate civil society

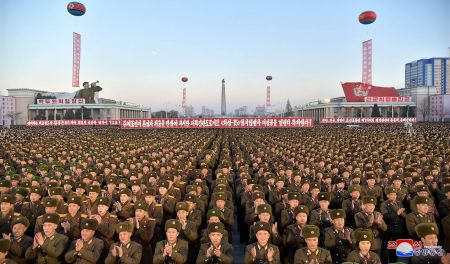

Scott’s last two criteria are probably opposite sides of the same coin: an authoritarian state able and willing to coerce society to bring high modernist ideals into being, and a subjugated population lacking the capacity to resist the implementation of high-modernist plans. Scott was writing in 1998, a few years after the collapse of communism and in an era when Francis Fukuyama and others were declaring the end of history, all battles won and so forth, so was a little shoe-shuffly about this. He needn’t have been! Not only have we seen the return of authoritarian governments and prostrate populations — for posterity I note I am writing from lockdown that has now lasted some nine months — but it has always been true of the corporate sector which is resolutely organised to be authoritarian, hierarchical and where you, dear employee, are administrated and ordered like no other participant on Earth. Every “meaningful”[5] aspect of your performance and your role is, at some level, reduced to a parameterised data point: ID, location, salary, rank, position, performance, reporting line, holiday entitlement, sick-leave, service catalog, objectives — let me know when you want me to stop. As for the high modernist ideal, well, this entire site is a paean to that, but strategy as we receive it seems entirely predicated on a deterministic, reductionist ideology that we can solve our landscape and then proceed sedately and without the need to be troubled by turbulent subject matter experts thereafter.

Metis

Speaking of subject matter experts brings us nicely to Scott’s closing, where he ruminates on the concept, missing from high modernist canon, of metis. This is hard to describe — folk wisdom, knowhow, Odyssean cunning — but in the corporate world it struck me as most resembling expertise. Ingenuity, problem-solving, lateral thinking; smarts for figuring out what to do on the fly if you are in a jam. This is something that the high modernist programme seeks abolish — the theory being that loose cannon employees wandering around making snap decisions is potentially catastrophic, and jams of this sort can and should be avoided by appropriate planning: thus, subject matter experts aren’t needed.

There are two interesting observations here. The first is that metis is much more efficient. You could — if you accept the reductionist stance — solve any problem with the right calculations, but the necessary data and processing power would be huge: but practical knowledge — metis — is “as economical and accurate as it needs to be, no more and no less, for addressing the problem at hand.”

This is the difference, says Scott, between Red Adair[6] and an articled clerk. There are some skills you cannot acquire except through experience. Likewise, learning to sail, ride a bike, or play a musical instrument. You could spend as much time as you like with textbooks, but you will never master riding a bike until you have done enough practical rehearsal.

Which brings us to the last connection: that to complexity theory, systems analysis and normal accidents theory. All of these come to the same conclusion: if you are dealing with complex systems, especially tightly-coupled ones with non-linear interactions, you cannot solve these with algorithms, no matter how much data and no matter how sophisticated is your conceptual scheme. The only way to manage these risks is with experts on the ground, who are empowered to exercise their judgment and make provisional decisions, and to adjust them as a situation unfolds. That is, with metis. If your conceptual scheme has systematically eliminated metis from your operation, you may carry on in times of peace and equability, but should a crisis come, you are stuffed.

See also

References

- ↑ Boss: “Yes, JC, I am. Now, get your coat.”

- ↑ Charles Perrow’s Normal Accidents theory; Systems Theory as expounded by Donella H Meadows, Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions

- ↑ It is said Chinese farmers gauged distance by “the time it takes to boil rice”, which provides a different, and more practical means of comprehending how far away you are

- ↑ It is of course a heresy to question it, but is any CEO really worth a hundred times the average employee that the firm pays for him?

- ↑ Meaningful to them, not to you.

- ↑ Younger readers may not remember this legend of the fire-fighting community.