OneNDA

Legal eagles love the idea that the standard, tedious terms that make up the lion’s share of commercial legal discourse are special.

|

The design of organisations and products

|

Then again, we all — not just lawyers — like to believe our own domain is sacred: that we are privy to something critical; dangerous; delicate — arcane learning that, should it fall into unskilled hands, may wreak great ill upon the bystanding world.

Make way: I’m a doctor.

But our dark secret: much of what we do, to get to those subliminal moments of rarefied artistry, we do on autopilot. To win Le Mans, first keep the engine tuned, the tank filled and the tyres pumped up. Then drive like Stirling Moss.

Boilerplate is the spark-plugs and fan belts of legal machine: workaday engineering that makes stuff go. What we want from it is reliability. It will not win us the race; it can stop us losing it, by working, dependably, without breaking down.

“Working” means being easily installed — without argument — and commonly understood; at the limit, being able to withstand scrutiny before the Queen’s Bench Division.

Curiously, that dependability is not intrinsic to the boilerplate itself: it is a function of what the community thinks it means. There is, therefore, a strength in consensus: if everyone uses it, it is more effective, by itself, regardless of the cleverness of its engineering. Law is a sociological phenomenon, first and foremost.

We should regard boilerplate as a public resource. We should not extract rent from it. We should not regard it as special. Lawyers don’t help anyone, or nourish their own souls, by acing boilerplate. So, folks, let it go. Set your boilerplate free.

The quotidian is a utility, not an asset.

Now, no legal form has more boilerplate than an NDA. To read one is to behold pure, abstracted, essence of boilerplate. Boilerplate is all there is. Yet generations of legal eagles have dug themselves into slit trenches to argue the toss over this quotidian contract. It has been some kind of insane compulsion: not one of them enjoyed it; not one of them saw any point in it; they found themselves compelled to do it; drawn to it like moths to a lamp.

“I must negotiate this NDA, because this is what I do. It is in my nature.”

Kudos, therefore, to the team at TLB for doing something about it.[1]

The JC put his sclerotic old shoulder to the wheel, for whatever that was worth, and commended his friends, relations and readers to do the same; especially those who occupy places in the firmament, or up the fundament, higher than his own.

Start with the NDA, who knows where it may lead?

Later ...

Well, readers, against his darkest suspicions, it looks like this OneNDA thing might work! The working group managed to defend against the inevitable special pleading, committee drafting, the pedantic culpa in contrahendo-style commentariat to which we agents of the tragic commons resort by irrepressible force of habit: through sheer willpower OneNDA generated a nice, simple, pleasant first edition. Not perfect — nothing is — but absolutely good enough.

It’s too early to stand on the poop-deck with a mission accomplished banner, but OneNDA is getting there. So, in a gentle further shove, here some observations about what it could all mean.

Simplification beats technology

A counter-intuitive proposition: if you simplify, you may not need technology. There is no need for automation, document assembly, even a mail merge is probably over-engineering. This is to observe that the conundrum facing modern legal eagles is not one of service delivery, but service in the first place. Fix the content, and the delivery challenges fix themselves.

This leads to a paradox: if you simplify properly, it is easier to apply technology. To design for technology, design for no technology. The fewer options, subroutines, caveats and conditions precedent in your legal forms, the easier you will find it to automate them. You will get all kinds of second order benefits too: fewer complaints, fewer comments, less time auditing your monstrous catalogue of templates.

The JC’s handy aphorism here: first, cut out the pies.

It’s not the form, or even the content, but the consensus that matters

Once upon a time — until 2021 —if you devised your own short-form NDA, however elegant, you could expect it to be rejected[2] or marked up to oblivion by the rent-seeking massive.[3]

Once — okay, if, but here’s hoping — the short-form NDA achieves wide-spread community commitment the dynamic will be different. Those who built it would use it, sure. But those who didn’t would look upon it not with suspicion, but with trust: “this is a community standard: I can get comfortable using it too”. No-one got fired for following the crowd.

OneNDA is a community effort: interested people came from far and wide to help; everyone[4] checked their agenda at the door. This was what Wikipedians call “barn-raising”. The community came together for the greater good of all.

Now once a barn is raised and community feels ownership in it, it is the very fact of the barn, rather than how it was built or what it is made of, that is its value. Community assets accrue to the benefit of everyone. The structure, day one, might not be perfect — is anything? — but nor is there any interest in undermining it, much less setting fire to the roof: it is in everyone’s interest that the barn does the job it was built for. Everyone has skin in the game. The more people use it, the more they are incentivised to make sure it stands. The more people use it, the more “good enough” becomes “perfection”.

Thus, technical complaints that, for example, it refers to “the public domain” and not just “public” — I mean, what a zinger — fall away because (if they didn’t already) everyone knows what it means. If there are ten thousand standard NDAs out there that use the expression “public domain”, then no court (and, frankly, no plaintiff) is going to side with a pedant against the weight, and interests, of community consensus.

The hard lines discourage rentsmithing around the edges

Once that common standard exists, with the hard lines OneNDA has drawn around itself, there is a further subtle advantage: it will dampen peripheral legal-eaglery around small, irritating edge cases (not to mention out-and-out pedantry).

We all know the common fripperies thrown into negotiation of an NDA by way of a dominance display between legal eagles: indemnities; exclusivities; non-solicitation; licencing and so on. Where notices these will quickly be rejected out of hand, the courtship display required to remove them is still tedious and it takes time.

But it is hard to rentsmith without a “host” contract. By drawing hard lines around itself, the OneNDA makes itself unavailable to act as that host. It frustrates the rentsmith. The party wanting them has to create a new agreement for the purpose, but it is not likely to do that for fear of looking stuipid. The standard template discourages peripheral negotiation. This is an additional, unintended benefit.

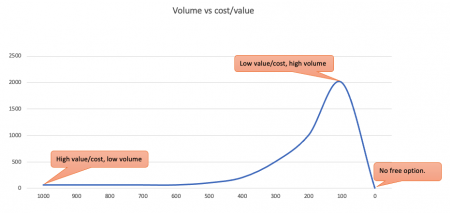

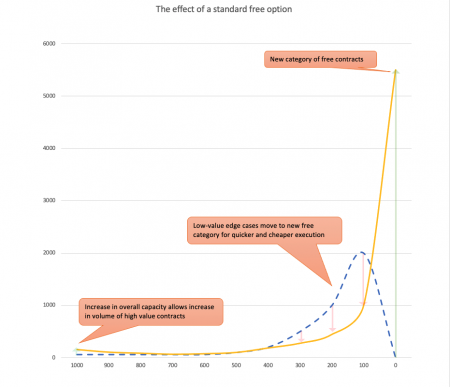

The knee of the curve

Creating a simple and standard alternative has a nice effect, too, on the legal complexity curve. It pulls it down and to the right. These are the directions you want it going in. These fancy charts are stimulations of a real-life situation. The problem: a broken contracting process. Our solution: standardise and automate just the simplest, lowest value contract, leaving the process for the rest untouched. The intention was to reduce the workload of the negotation team, giving them more time to focus on the higher value, more difficult contracts.

The experiment was successful. Ovvernight, half the contract volume was automated. Additional benefits we did not expect were the following:

- Volumes in the automated contract doubled overnight: now it was cheaper, easier to execute, and with guaranteed no errors, the marginal cost went down, so the capacity to execute went up.

- Some “marginal” customers in the adjacent negotiated contract categories elected to move to the free model too: they were happy with the trade off of ”no custom terms” but “contract executed for free and immediately”. Thus the “knee” of the curve deepened and shifted to the right.

- volumes in the higher value negotiated contract categories increased, as the negotiation team had more bandwidth, processed the contracts more quickly and with fewer errors.

- As a result, total output of the team doubled.

The one thing that did not happen was the forced redundancy of the team. They were busier than ever, only on more challenging stuff.

See also

References

- ↑ Don’t just read about it here: go see: https://www.onenda.org

- ↑ There is a “battle of the forms”, even if not apparent to the doyen of drafting.

- ↑ The JC knows this, because he’s tried it. No counterparts clause! No waiver of jury trials! It was still worth doing, but it didn’t completely solve the problem.

- ↑ Everyone except the doyen of drafting himself, that is: https://www.adamsdrafting.com/onenda-is-mediocrenda-thoughts-on-a-proposed-standard-nondisclosure-agreement/