Carry trade

Carry trade

/ˈkæri treɪd/ (n.)

|

Carry doesn’t live here anymore

Carry used to price at flat LIBOR

Sorry that she left no forward address

Because her main financing was in distress.

- —Riff Clichard, Carry (1982, needless to say, a time of usurious interest rates)

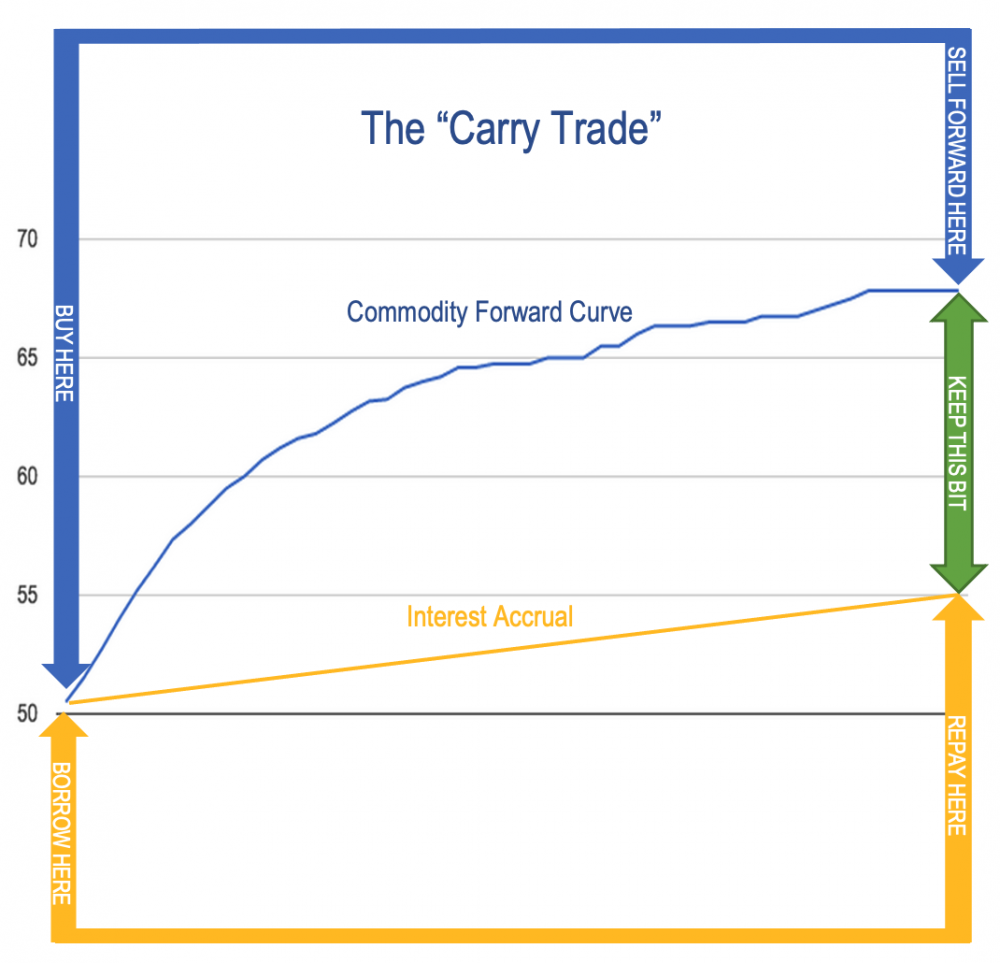

A transaction where one takes advantage of the market’s present opinion about its own future — most commonly expressed through the prism of the futures market — where that opinion is that an asset’s price will rise at a rate greater than one can borrow the cash required to buy it.

“Positive carry” describes the state of affairs when the the implied cost of financing an asset, as well as actual costs of holding it and ensuring — insuring — you don’t lose is less that the rate at which the asset appreciates. This means you can do a “carry trade”: borrow money to buy the asset now, immediately arrange to sell it at its forward price later, hold the asset for its term, and pay down your loan with the sale proceeds you receive at the end.

===Yen carry trade===Hence, the famous “yen carry trade”, in fashion in that period in the noughties where ¥ interest rates were low or even negative, and, for example, New Zealand Dollar interest rates were around seven percent. Since the kiwi was not depreciating against JPY at 7 percent per annum, good money could be had by borrowing yen and buying kiwi. This was a good trade as long as the JPY/NZD exchange rate didn’t tank. During 2000 and 2007, not only did the kiwi not tank against the yen but, to the contrary the yen tanked against the Kiwi, largely because so many people were borrowing Yen and selling it to buy Kiwi. So not only did you lock in a 7% interest rate for the best part of a decade, you only had to pay back half of the principal you borrowed in the first place. When the Yen then rallied 98% in the next 18 months, a few people might have taken a bath, but even then the rate nebver got back to its historic high

If you can see that the spot price of an asset today is lower than its forward price (as implied by the futures price) — that is, the forward curve is in “contango” — by an amount greater than your cost of funding, then all you have to do to make money is

- Today, borrow the money you need to buy the spot asset at your cost of funding for a term until your desired point in the future

- Today, buy the asset in the spot market at its spot price;

- Today, agree to sell it forward at that point in the future when your term funding matures, at its forward price

Then, just sit on the asset and wait. When the point in the future comes:

- On expiry, deliver the asset against payment of the agreed forward price (which may or may not be the prevailing spot price)

- On expiry, from the proceeds of your sale, repay principal and interest on the loan you borrowed in step 1.

- Keep the rest.

Works with any asset that has an observable forward market. Things that can go wrong:

- Your asset can go off, get lost, or be nicked (especially if a commodity in some warehouse in the Sudan)

- You have to pay the costs of holding it, so don’t forget those

- The person to whom you sold it forward may have blown up in the meantime (but hopefully you’ll be taking margin from them so less of a bother).

- Don’t forget to make sure the forward curve is in fact in contango, and the yield exceeds your cost of funding. Schoolboy errors, but these do happen.

Happy days!