Empathy and compassion

To paraphrase Rasmus Hougaard,[1] empathise is to join in with someone else’s suffering without necessarily doing anything to help. To be compassionate is to recognise suffering, but step back from it and ask “how can I help?”

|

Hougaard ’s four reasons:

Empathy is impulsive. Compassion is deliberate.

Empathy is the impulse that makes you cry at the movies. It doesn’t come from a rational place. It is not the output of a deliberative function. Now we have have doubts about homo sapiens’ capacity for logic at the best of times, readers, but when you act based on empathy you are not even trying to be logical.

We like to think it leaders are logical: slower rather than hasty to react, considerate of all positions and constituencies. We would rather a leader did not act at all than acted precipitately.

Being instinctive, the empathetic instinct is not necessary fair, equitable or just. It comes from the animal brain. It favours kin, familiarity, and reinforces our prevailing values and worldview. It shoots without asking questions.

Empathy is divisive. Compassion is unifying.

To be empathetic is to walk a mile in someone else’s shoes, to live their lived experience; to look at the world from their perspective. It is to take sides. This is something to value in the family dog, and your own mother. Not a leader. Leaders have to be independent, to have no interest in the matter, and recuse herself when she does. Leaders need sometimes to make decisions their subordinates might not like, and sometimes to arbitrate — to settle disputes between subordinates that at least one of them definitely will not like.

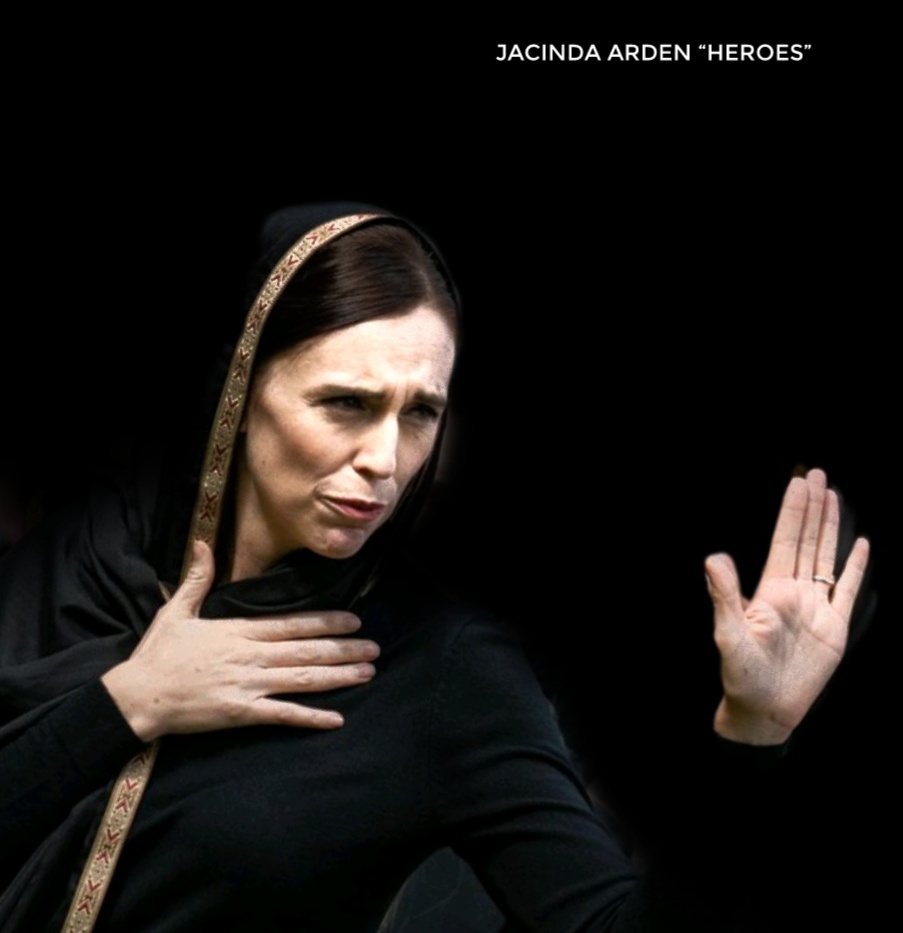

In our postmodern, morally relativistic times, the opportunities for leaders to take sides and get away with it — where there is a consensus good guy against an old school Bond villain antagonist — are rare indeed. Jacinda Arden who branded herself an empathetic leader had a couple of rare opportunities with unexpected white supremacist terrirism, and murderous volcanoes. But even the early throes of pandemic proved harder to manage when it turned out she was responsible for multiple constituencies whose interests conflicted, and she couldn’t empathise with all of them.

Since empathy is instinctive, we also tend to empathise with those closest to us, who was can most easily identify with.

Empathy is inert. Compassion is active.

Empathy is to join in, to wallow in someone else’s problem, to colonise it, without necessarily doing anything to alleviate it. Alleviating the problem — if there is a problem — brings the need for empathy to an end, so the truly committed empathist does not want the problem to end, for that way lies the end of empathy.

We see this in a lot of “focus groups”. When the battle has been won, who wants to pack up the banners and go home?

Should we empathise with those who have no problems? It isn’t clear what this would involve — how do you empathise with Elon Musk? Would he care if you did — but the closest we can think of is sports allegiance. You know how much fun Manchester City fans are when they’re winning? The only time they’re worse is when they’re losing.

Empathy is draining. Compassion is regenerative.

Ram-raiding someone else’s grief is exhausting, and also a downer. Especially if, as should be the case for a true empathist, the unstated goal is to perpetuate it, and make room for a mutual sobfest.

Rather, thinking laterally about how to alleviate suffering — being constructive in the game of bucking people up and get them to look on the bright side — we fancy is rather energising.