Iteration

|

The design of organisations and products

|

Iteration

iteration (/ˌɪtəˈreɪʃn/.)

Incremental modification to a process, product or theory as a means of refining it, improving it, and recalibrating its fitness and suitability to a changing environment.

A key, and much underestimated, quality in our crazy sugar-coated world. Where you are confronted with imperfect, incomplete or conflicting information, variables that are beyond your control (children, animals, opposing ISDA negotiators), unknown unknowns — in short, complex systems — then your decision making process should be iterative.

To iterate is to hypothesise; to guesstimate, to test; to tweak; to rerun. To accept that, since there is imperfect, incomplete information, any decision and any design choice is to some extent uniformed, but since, when a programme is malfunctioning, some remedial action, is likely to be better than none, your best bet is provisionally to take as informed a decision as you can, based on what you do know, for now, but be ready to re-test that idea and change your action as the situation, and the information you have to hand about it, changes.

That is, you should iterate. The decision process is not static, it is not preordained — it is an ongoing dynamic process.

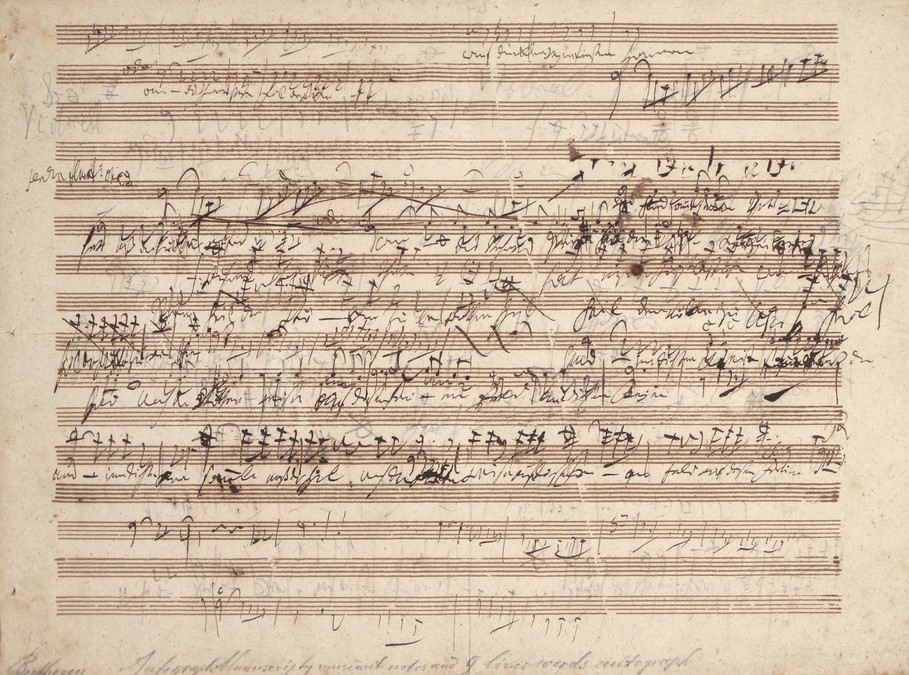

This principle applies whether you are solving new problems, dealing with an unexpected crisis, or building out your system — the end-to-end principle allows maximum iteration. Don’t be wedded to the way you’ve been doing things — I know, I know my little eaglets, it is so hard to let go of the comfort blanket of precedent, but you must — try, and expect things to fail. Don’t commit. Scrub them out and try again.

Iteration requires skill

Even without someone actively trying to stop you, successful iteration is hard. The more you practice, the more you understand the systems and subsystems of your environment, the better you will be. Expertise, skill and experience matter.

Our old friends the itinerant school-leavers from Bucharest might be cheap and fungible, but they won’t, off the bat, have the expertise needed to effectively iterate. She will only get that expertise by iterating. When she does get that experience she will pack up and relocate to London, so it remains true that school-leavers from Bucharest, whilst in situ, will not be the droids you are looking for. They will come and find you when they are ready.

Not all iterations work. The thing about tail events is they’re hard to predict. On the other hand, an iterative process will almost certainly be more effective than a chatbot at dealing with a novel conundrum. And trying something that doesn’t work still yields you information: it is a falsification: now know what isn’t the answer.

The forces of inertia are against you

You have to work at iteration, and fight those who would bid you stop. That you continue to iterate is to acknowledge you have a work in progress. This can be annoying, especially to people who don’t like to admit things are a work in progress.

But everything that is not dead is a work in progress.

There will be strong impulse against iteration from people in the organisation:

- Those fearful of upsetting clients, especially on repeat business, or once a termsheet has gone out: “for god’s sake don’t change anything!”;

- Those — and they tend to be more senior people — who know what they know and like things how they are (this being the way things were that got them where they are);

- Those who believe in reasoning from settled principles. Lawyers tend to belike that. The common law is predicated on being like that.

“If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it” is the anti-iteratist’s stance.

Other articulations

- Think of the world in terms of systems, not units — Donella H. Meadows

- Prisoner’s dilemma — the payoffs are totally different if you play an indefinite-round game of prisoner’s dilemma (hence the so-called “iterated prisoner’s dilemma”). But note the impact of convexity, that can turn an iterated game into a single round.