Finite and Infinite Games

James P. Carse: Finite and Infinite Games: A Vision of Life as Play and Possibility (1986)

|

“It wasn’t infinity in fact. Infinity itself looks flat and uninteresting. Looking up into the night sky is looking into infinity — distance is incomprehensible and therefore meaningless. The chamber into which the aircar emerged was anything but infinite, it was just very very very big, so big that it gave the impression of infinity far better than infinity itself.”

Ostensibly, Finite and Infinite Games is a 40-year-old tract of cod philosophy from an obscure religious studies professor. It might well have silted into the geological record — somewhere between Erich von Däniken and Francis Fukuyama — i.e., destined never to be heard from again until it is recycled for peat — but having been picked up by Simon Sinek[1] it is having a fertile third age, and when minds as luminous as Stewart Brand’s speak reverently of it, it seems there is life above the daisies for a little while yet.

Hope so.

In any case Carse’s central idea is this: there are two types of “games” in the world: “finite” ones — zero-sum competitions played to win — and “infinite” ones, played to continue playing.

Finite games are from Mars, via Thomas Hobbes; infinite ones from Venus, via Adam Smith.

A finite game is, in the narrow sense, a contest: fixed rules, fixed boundaries in time and space, an agreed objective and, usually, a winner and a loser. For example, a football game, boxing match, a dog-fight or a board game.[2]

An infinite game is more like a “language game”: no fixed rules, boundaries, or teams; participants can agree change rules or roles as they see fit to help play to continue. For example, a market, a community, a business, a team or a scientific paradigm. These are (Q.E.D.) nebulous arrangements, of course, but one thing they are definitely not is contests. There are no winners and losers in an infinite game, since the idea is to avoid a final result.

You may play multiple, interlocking, nested finite games at any time, and you can even embed finite games into infinite ones — though, for obvious reasons, not vice versa — so it is important in life not to confuse one’s finite and one’s infinite games.

The thrust of Sinek’s book is that much of modern life does confuse them: that when we carry over the metaphors of sport and war into business and politics and play infinite games to win — that is, as if they were finite games — we make a category error. By doing so we may find ourselves excluded from the game while others carry on. We may find our finite objectives hard to pin down, let alone achieve.

That said, the distinction is less tractable than it at first appears. A football match is finite; a football team is infinite. A team plays each match to defeat its opponent utterly; in the wider league, it needs its opponents to survive and flourish, so it can continue to play against them, and so that there is the realistic prospect of what Carse calls “drama” (and not merely “theatrics”) on the field. While a football team never wishes to lose any particular match, in the long run it must lose some matches in general, lest there be no drama: spectators and players get bored. No-one wants to be beaten every time. No-one wants to win every time. No-one wants to watch a foregone conclusion. Ergo, we play finite games in the context of a broader infinite game.

Carse, who died last year, was wilfully aphoristic in his literary style. This is off-putting.[3] He would often write things like:

The paradox of genius exposes us directly to the dynamic of open reciprocity, for if you are the genius of what you say to me, I am the genius of what I hear you say. What you say originally I can hear only originally. As you surrender the sound on your lips, I surrender the sound in my ear.[4]

Now this is important, but it would have been better — or, at least, more fathomable — had he explained better what he means by this. That said, this passage assigns as much credit for successful communication to the listener as to the speaker, so perhaps this is the very point. Maybe Carse meant to leave room for listeners to make what they will of his mystic runes. In any case, making head or tail of these cryptic aphorisms is a kind of infinite game of its own — one that Mr. Sinek is playing pretty well. So, let us join in.

Carse invites us to reframe activities we might see as existential struggles instead as opportunities to build a different future: all it requires is players who are skilled at the infinite game. This he does by means of a number of dualities:

“Historic” versus “prospective”

“We were seeing things that were 25 standard deviation moves, several days in a row”.

- —David Viniar, Chief Financial Officer, Goldman Sachs, August 2007.

Many distinctions between finite and infinite games boil down to their historical perspective: those that look backwards, concerning themselves with what has already been established and laid down — as agreed rules, formal boundaries and limited time periods for resolution necessarily do — will be finite in nature; those that are open-ended, forward looking, and indeterminate — concerned with what has yet to happen are infinite.

Historically-focused finite games are fine: there is no harm and much reward to be had from a game of football, as long as everyone understands the “theatricality” of what is going on; but to apply finite, backward-looking techniques to the “resolution” of infinite scenarios — necessarily forward-looking, indeterminate problems (in that you don’t even know that there is a problem, let alone what it is) will get you into bother.

Yet, finite techniques may work perfectly well much of the time, because for long periods infinite environments may resemble finite games. In ordinary conditions, business proceeds by reference to an established order, existing conventions and what is already known. Rules feel fixed. Competition is apparent.

As long as your environment behaves like this, a “historic” approach is efficient and effective. Exercising central control as if one were playing a finite game provides consistency and certainty. This is why thought leaders are so fond of sporting metaphors.

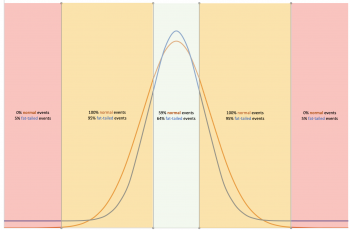

But it is just an other way of noting that the middle of a normal distribution resembles the middle of a “fat-tailed” distribution and the same approaches will work passably well for both, as long as the events fall within the middle, which for the most part they do.

It is also, let us hazard, why senior executives in large corporations get paid so much money. When events are within a couple of standard deviations of the mean — as, for the most part they are — central control seems a capital idea, and well worth paying for.

When a wicked environment goes all kooky on you — as surely it will from time to time — and your executive leaders start telling you something that has happened three times this week already shouldn’t have happened one in several trillion trillion lives of the universe, it may feel like you’ve been paying for talent in all the wrong places in the organisation.[5]

“Power” versus “strength”

“A powerful person is one who brings the past to an outcome, settling all its unresolved issues. A strong person is one who carries the past into the future, showing that none of its issues is capable of resolution. Power is concerned with what has already happened; strength with what has yet to happen. Power is finite in amount, strength cannot be measured because it is an opening and not a closing act. Power refers to the freedom persons have within limits, strength to the freedoms persons have with limits.

Power will always be restricted to a relatively small number of selected persons. Anyone can be strong.”[6]

It is fashionable in our time to speak loosely about “power” — much of critical theory is a manifesto against the violence power structures do to the marginalised — and Carse’s distinction between “power” and “strength” is a good reminder to exercise care here.

Sure, social hierarchies can be pernicious, where operated by those engaged in a fight to the death, but most people are not. Critical theories themselves are paradigms — social hierarchies of just this kind. Those who who favour any form of communal organisation more developed that flapping around in primordial sludge will concede that social arrangements don’t have to be destructive: they can be constructive, enabling, levers to prosperity and betterment for everyone who wants it. If we call such a centralised, curated, defended store of knowledge for sharing a “strength structure” it does not sound so ominous.

“Strength is paradoxical. I am not strong because I can force others to do what I wish as a result of my play with them, but because I can allow them to do what they wish in the course of my play with them.”[7]

“Society” versus “culture”

“Society they understand as the sum of those relations that are under some form of public constraint, culture as whatever we do with each other by undirected choice. If society is all that a people fells it must do, culture “is the realm of the variable, free, not necessarily universal, of all that cannot lay claim to compulsive authority”.[8]

Perhaps Carse would describe a power structure as of “society” and a “strength structure” as of “culture”. The historic, zero-sum nature of finite games contrasts with the prospective, permissive nature of infinite ones.

Society is finite, bounded, and patriotic: functions to establish a hierarchy, bestowing titles, honorifics and awards — the emblems of past victories in combat, and markers of power —to grant certain participants formal status. One desires the permanence of society because it vouches safe the permanence of one’s titles and prizes.

Culture is infinite, unbounded, endlessly creative and sees its history not as destiny, but tradition: a narrative that has been started but is yet to be completed and that may be adjusted as required. Just as one can can play finite games within the context of an infinite one, so can there be society within culture.

The “theatrical” versus the “dramatic”

Inasmuch as a finite game is intended for conclusion, inasmuch as its roles are scripted and performed for an audience, we shall refer to finite play as theatrical. [...]

Inasmuch as infinite players avoid any outcome whatsoever, keeping the future open, making all scripts useless, we shall refer to infinite play as dramatic.

Dramatically, one chooses to be a mother. Theatrically one takes on the role of mother.[9]

This is a harder distinction to glom, especially since Carse concedes that during a finite game the action is “provisionally” dramatic, since the players write the script as they go along. But the object of the game is to kill the drama by making the outcome inevitable. So provisional, and hostile, to drama.

The value of artists

A society that wishes to transcend itself and stay in touch with its culture must embrace its “inventors, makers, artists, story-tellers and mythologists”: not those who deal in historical actualities, but who help imagine new possibilities for how the culture might be.[10] Their mode of engagement having no particular intended outcome or conclusion, they can appear hostile to those already holding rank, title or position in society, and who would rather shore up the historical record to validate their victories.

Society is ambivalent towards the dreamers and malcontents who imagine a different order — they once broke Mick Jagger on a wheel; now he’s a peer of the realm[11] — but they operate not by directly confronting the established order, but by sketching out an imagined alternative which eventually takes root.

“Training” versus “education”

A centrally-guided automaton needs only training; an autonomous agent playing a finite game needs education.

“To be prepared against surprise is to be trained. To be prepared for surprise is to be educated.”[12]

Players of finite games train.

A master tactician works out moves, devises playbooks, and solves equations for them, presenting all to the players for ingestion and later regurgitation.

All being well, by clinical execution, players overcome their opposition. The team that wins is the one that executes the master plan most effectively. Players should not improvise, for that risks upsetting the master plan. A player’s judgment is limited to selecting which part of the master plan to execute, when and in response to what. Preparation is everything. The idea is to eliminate surprise by having, as far as possible, worked out all possible permutations in advance, and where computing all possible outcomes is not possible, to have computed more possible outcomes than your opponent.

This is the modernist, computerised model of operation: fast, cheap, accurate calculation. The last thing you want is variability, or a player using her initiative: that can ruin everything.

Players of infinite games need education.

Training works where all parameters are fixed and all possible outcomes at least knowable in theory — zero-sum games, simple systems, football matches — but does not always work in the dancing landscapes of complex adaptive systems.

If you have prepared for chess, your work will be for naught if the game morphs into draughts — or, just as likely, cookery, music, electronics, or a dialogue about conceptual art. Here, instead of eliminating surprise, you equip yourself to deal with it: you need not answers but tools, heuristics and a facility with metaphor.

“Complicated” versus “complex”

Finite games are complicated.

Complicated systems require interaction with autonomous agents whose specific behaviour is beyond the observer’s control, and might be intended to defeat the observer’s objective, but whose range of behaviour is deterministic, rule-bound and known and can be predicted in advance, and where the observer’s observing behaviour does not itself interfere with the essential equilibrium of the system.

You know you have a complicated system when it cleaves to a comprehensive set of axioms and rules, and thus it is a matter of making sure that the proper models are being used for the situation at hand. Chess and Alpha Go are complicated, but not complex, systems. So are most sports. You can “force-solve” them, at least in theory.

Complicated systems benefit from skilled management and some expertise to operate: a good chess player will do better than a poor one, and clearly a skilled, fit footballer can execute a plan better than a wheezy novice — but in the right hands and given good instructions even a mediocre player can usually manage without catastrophe. While success will be partly a function of user’s skill and expertise, a bad player with a good plan may defeat a skilled player with a bad one.

Given enough processing power, complicated systems are predictable, determinative and calculable. They’re tame, not wicked problems.

Infinite games are complex.

Complex systems present as “wicked problems”. They are dynamic, unbounded, incomplete, contradictory and constantly changing. They comprise an indefinite set of subcomponents that interact with each other and the environment in unexpected, non-linear ways. They are thus unpredictable, chaotic and “insoluble” — no algorithm can predict how they will behave in all circumstances. Probabilistic models may work passably well most of the time, but the times where statistical models fail may be exactly the times you really wish they didn’t, as Long Term Capital Management would tell you. Complex systems may comprise many other simple, complicated and indeed complex systems, but their interaction with each other will be a whole other thing. So while you may manage the simple and complicated sub-systems effectively with algorithms, checklists, and playbooks — and may manage tthe system on normal times, you remain at risk to “tail events” in abnormal circumstances. You cannot eliminate this risk: accidents in complex systems are inevitable — hence “normal”, in Charles Perrow’s argot. However well you manage a complex system it remains innately unpredictable.

Top-down versus bottom-up

In team sport, a central manager who can plan ahead, instil in players a defined set of pre-formulated tactics, plays and set-pieces: and an on-field captain to direct operations as the game unfolds they are executed is a powerful strategy. Under these circumstances a team of ordinary players may prevail over a disorganised assembly of better athletes. This is the lesson of Michael Lewis’ Moneyball: The Art of Winning an Unfair Game.[13] This works precisely because rules are fixed, variables are known, and there are tight parameters around what players can do, where they can do it. Sports — and other finite games — are responsive to top-down management.

Now if business is a finite game, there is much to take from this. In such an environment, form dominates substance: we should have our best minds formulating rules working out algorithms and devising playbooks and sourcing players who will faithfully and unquestioningly follow the plan. Success is a simply a matter of who had the better plan, and who executed it best. This, in turn, has a few implications about how we configure the organisation:

Firstly, it means the brilliant minds belong at the top of the organisation: they do the most inspired thinking. They come up with the best plan. Securing “the man with the best plan” is worth paying extraordinary amounts of money for.[14]

Secondly, it means the organisation’s sacred quests are the creation of excellent process and optimising the cost of carrying it out. Our most talented personnel are those who can write formal rules, and build machines that reliably follow them.

Thirdly, it means those in the organisation whose job is not to formulate policy but to carry it out — those who must put the leadership’s plans into practice — must not think: they must, so far as possible, just follow instructions: quickly, flawlessly, cheaply. They should act like automatons. If your special sauce is your central strategy, the last thing you want your players to do is improvise.

Those with an interest in modern management philosophy — or, we dare say, a job in a modern multinational — might recognise this disposition. But note the drift: for operational staff it is towards efficiency; for administrative staff it is towards excellence. Excellence in building, maintaining and refining machinery.

Now business is an infinite game, we have a different proposition. Since the rules aren’t fixed and we can’t predict what opposing players will do — or for that matter who’s even playing — and as there is no end-goal in particular other than to avoid arriving at an end — a pre-determined strategy will not work. Indeed, the very idea of a predetermined strategy is incoherent.

Instead, every player must constantly assess her environment and act based on the information she currently has. Here a “coach” is little more than a central coordinator supplying information and resources to help the players make their own tactical decisions as the need arises so they can keep playing. We want our players to be virtuosos with freedom and resource to carry on and augment the game. We need our infrastructure to be simple, robust and permissive — enabling communication, allowing the players to dynamically reallocate resources as they see fit. Management’s overarching goal should be to empower quick and effective decision-making in the field, but otherwise to keep out of the way.

Seeing as the idea is not to win but to continue, conferring discretion upon those who directly engage with the complex adaptive system outside is not catastrophic as long as the individuals are experienced experts: they must not act like machines, and empowered — trusted to deal with unfolding situations as they perceive them.

This is quite the opposite model: here the greatest value is provided at the edges of the organisation. The bottom-up model: laissez-faire; invisible hand; evolutionary.

“Formal” versus “substantive”

We have argued elsewhere, at tedious length, that the great curse of modernity is the primacy of form over substance.

In finite games the distinction between the two can be trivial; in an infinite game it is not.

In a backward-looking, proven, data-complete universe, substance is simply a specific articulation of form. The universe is solved; there is an exclusive optimal move and it can be derived from first principle. Substance follows from — is dependent on — form. Form is an axiom; substance is its articulation with numbers. If you have right equation — that is to say, if you follow the right form — you will get the right answer. Indeed, without the right form you have almost no chance of getting the right answer, and none at all of knowing that you have it. This depends on the universe being bounded, all rules determined, all knowns known. It depends, therefore, on the conditions existing for a finite game.

Where the universe is not bounded, where rules are unknown or changeable, where unknowns swamp knowns[15] — where the game is infinite — substance is not a function of form. There are no equations, axioms or formulae to follow when interacting with complex adaptive systems. It will be tempting to rely on formulae that tend to work most of the time — the Black Scholes option pricing model works most of the time, at least until it does not — but this is a lazy and, as Mr Viniar’s shareholders found, dangerous economy.

Instead of an army of the trained carrying playbooks containing the pre-baked tactics of a super-coach, we need the educated: those best equipped to observe, orient, decide and act — if combat is required — or collaborate, if it is not. People who can do this well must necessarily be skilled, experienced and therefore expensive — but none is anything like as expensive as a super coach.

Problem cases

Finite and Infinite Games is a theoretical tract — a work of abstract principle, not a practical guide — and while it is a useful means of framing a different approach to business and a powerful tool for disarm our intuition that business leaders are worth the compensation they are paid. But they cannot solve the intractable messiness of the real world. Bad things happen, and even a distributed network of empowered subject matter experts is fallible.

You cannot switch overnight

Multinationals have been in thrall to the cult of the chief executive for decades. The firm’s design choices, big and small — the way it structures its business, how it organises operations, who it hires to do what — all are predicated on the modernist disposition that genius lies in formulating that central strategy, and that day-to-day management is a matter of efficiently carrying it out. We don’t hire experienced, expert improvisers to do “service delivery” — we hire school-leavers from Bucharest and give them a user manual. Those who stay on and progress do so not because of their talent for extemporising, but because they are excellent — meaning fast — at following instructions. The organisation fashions itself over time in its own image. Should the scales fall from your eyes, you cannot command an over-managed multitude of rule-followers to suddenly “be agile” or “creative” — at least not without dispensing the management superstructure that sits over them nannying them into doing no such thing. Modernist approach is a matter of culture and culture sits deep in the ontology of the system. Culture moves very slowly. It cannot change overnight.

The Christians, atheists and their interminable games

A particular type of argumentative youth — it may not shock you to find that the JC was one, once — will take delight in forming abstract and highly artificial positions from which to launch highly formalised denouncements of the views of an anyone holding a contradictory abstract position while opponents to just the same thing back

This used to happen in town squares and speakers corners, and now mainly happens on Twitter.

These games account for much of modern public discourse, but do not easily fall into Carse’s rubric. Each player’s ostensible goal is to win by proving definitively that his opponent is wrong.

This therefore has the appearance of a run-of-the-mill two-hander finite game: fixed rules, fixed sides and ostensibly clear success criteria — except that it is nothing of the kind, as there is no time boundary and the named of the game is to keep going which, as long as you're opponent still had breath in him, you can happily do, as each side wittingly, if not willingly, supplies intellectual straw men for his opponent to carry on knocking down.

Axiomatic that neither player will ever accept any opponent’s argument as a decisive, or even wounding, blow, and play will continue without conclusion, to the great delight of all participants (though it is a delight which presents as studied outrage at what the opponent is saying, but is really nothing of the kind) and the profound ennuyeux of everyone else.

There are many flavours of these games — they are not finite or infinite so much as interminable: left versus right; Brexit versus Remain, anything involving critical theory or social justice, religion, political orientation or football team primacy.

See also

References

- ↑ The Infinite Game by Simon Sinek (2019) (see here).

- ↑ Notably, both Chess and Go are finite games.

- ↑ Notably, Carse’s speaking style is much less cryptic and talks he gave about the infinite game concept are worth checking out. See for example his talk to the Long Now Foundation: Religious Wars in Light of the Infinite Game.

- ↑ Carse, §51.

- ↑ You would expect a “25-sigma move” on one in 1.3 billion billion billion billion billion billion billion billion billion billion billion billion billion billion days, which is several trillion trillion trillion trillion times as long as the life (to date) of the known universe. More on this fascinating topic on our normal distribution article.

- ↑ Carse, §29.

- ↑ Carse, §29.

- ↑ Carse, §33 (citing Carl Jacob Christoph Burckhardt).

- ↑ Carse, §15.

- ↑ Unhelpfully, Carse calls these people “poietai” — from Plato’s expression, a label hardly calculated to make his work more penetrable.

- ↑ Redemption comes at you fast: in a notorious interview in 1976 Bill Grundy compared these new “punk rockers” the Sex Pistols to “the nice, clean Rolling Stones” who had, not 11 years earlier, been outraging public decency with their subversive tunes about onanism.

- ↑ Carse, §17.

- ↑ It is also the falsification of Anita Elberse’s Blockbusters: Why Big Hits and Big Risks are the Future of the Entertainment Business. The “Galácticos” strategy of buying the best players money can buy, thereby emphasising individual talent, over central management and tactical excellence has generally had disappointing results (at least on a cost/benefit basis) for those franchises who have tried it.

- ↑ Goldman Sachs to pay one-time bonuses of $30 million to CEO and $20 million bonus to COO.

- ↑ All data is from the past. Seeing as there is an infinite amount of data from the future, the portion of the available data we have is, effectively, nil.