Path-dependent

Path-dependent

/pɑːθ-dɪˈpɛndənt/ (adj.)

|

The JC’S favourite Big Ideas™

|

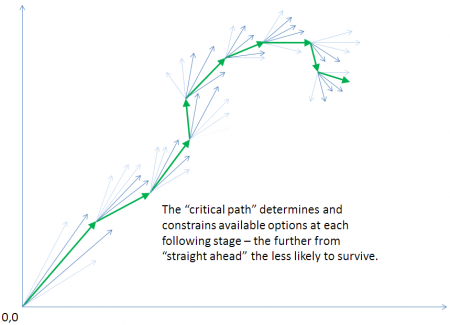

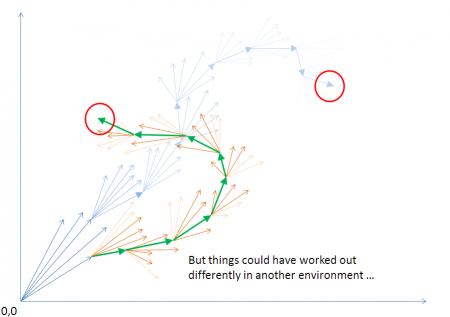

Of a circumstance, that its coming about can only be explained by the sequence of events and contributing factors that lead to it; that it cannot be justified or explained by reference only to existing conditions.

The way things turned out depended on the coincidental interaction and juxtaposition of unrelated factors in the ecosystem.

The classic case is of course evolution by natural selection: re run the tape from the beginning and you would not get the same result.

Backtesting, how how “hindsight is a wonderful thing”

Backtesting is a naked way of trying to solve for the future by extrapolating from the past.

It is so naked that these days only the mendacious or the dense have any truck with it. Of course, the mendacious and dense tend to get on pretty well.

The idea is this: collect and analyse years of market data — back through the last meltdown, ideally — and from it construct the optimal trading strategy, that, had one used it, would have returned the greatest profit, and have totally avoided the fallout of that meltdown.

Of course no-one knew at the time how the meltdown would play out, so no-one used this brilliant strategy.[1] For had we known trading patterns would have been different, the data would have come out differently, thereby confounding the strategy.

Backtesting is a preposterous idea.

By the lights of history, the market’s course is now fixed. The data is dead. Inert. But when you are there, in the moment, it is not. It reacts to you, and you react to it. It is dynamic. Symbiotic. Contingent. Alive.

A trading strategy derived from the fossil record of data that was once alive, but is now not, is similarly inert. It is cannot ride, or get swamped by, the symbiosis between market and participant.

This is true of any algorithm that depends on data. Data is history. A photograph. It is good for answering questions to which there already is an answer. (Don’t scoff at this: many good questions are things for which there is already an answer; just one we don’t personally know. Hence: the value of Google. The value of a library.)

But note the mode of discovery: static; historical; final; determinate. Data can tell you how things were.

Causal determinism

We accept “causal regularity” — that science yields truth: that one thing regularly leads to another — because the alternative seems to deny the apparent operation of the universe.

But even here the fossil record flatters to deceive: the lattice of potential causes is far more complex than our wildest dreams — we form those just from what we see and hear — but that is an infinitesimal sliver of all possible events out there. Our histories are works of imaginative fiction. This is why historians do not agree. We make our histories; we do not find them.

By looking at a unitary history (that we made up), in hindsight we miss the contingency from which it was fashioned. Once it is laid down, it looks inevitable. It looks pre-ordained. This is a curiously religious idea.

In any case, even if there is but one past — whether or not we can know it — still there remains, from any given present, an infinity of futures.

The temptation, when we look at such a concrete past, is to see each of the points behind us on that timeline as having determined the remaining history to the present. The extrapolation is that they must determine the future, too. The further back in time a point is, the more momentous it has been in determining our path to here. This seems intuitive: the decisions I made yesterday had little bearing on where I am today: I was already here. The die was long since cast.

But this is not true.

Since that moment thirty-years ago, when you bought that plane ticket to America, you have had thousands of opportunities to buy a plane ticket home again. That you are still in America is nothing to do with that ticket you bought, and everything to do with the tickets home you haven’t bought since.

We have, and our ancestors had, the ongoing ability to change things daily. Everyone makes bad decisions. The key is not to be defined by them. Everyone makes good decisions, too. Keep the good decisions, do what you can to correct for the bad ones.

Our permanent aspiration: from here, make more good decisions than you do bad ones. Improve your ratio. You will not always know at the time. You will learn in hindsight. Iterate.

You can’t undo the decisions of the past, whether made by you or about you, or by your ancestors or about them. You can make different decisions now.

Pragmatist’s prayer and the infinite game

James Carse’s fabulous Finite and Infinite Games provides a great prism for framing these battles between the past and present. For what is a “lived experience”, a “grievance” or a “standpoint”, if not an articulation of history?

The future contains only as-yet unlived experiences. There are no grievances there. Our standpoints, the margins and their intersections are unknown.[2]

Being historical, an already-lived experience is permanent, and set in stone. It cannot be moved. It cannot be removed. It cannot be compensated for. It cannot be denied. It becomes a monument. A shibboleth. A sacred prophecy. But it remains our own imaginative construction.

We are autobiographers. Literally, we talk our own book. We choose by which significant events we define the trajectory of our own lives. We build our own memorials. We choose to live beneath their shadows. But our present is a function of every point in our past, not just the ones on which it suits us to now fixate as we construct our personal narrative.

To adopt — some might say “colonise” someone else’s personal narrative is the empathetic stance: to step into their shoes, to take sides, to exalt them and perpetuate their grievance. Empathy is to exalt history, whilst pretending to despise it.

But, look: standpoints iterate. As the present moves through space-time, we lay down the tracks of future, each new decision we make contributes to our lived experience. We update our standpoints — it is only by refusing to update our standpoint that we can optimise our grievance. There are people whose professional interests are served by optimising their own grievances. They are not fun people. They probably don’t have much fun. Don’t be like that. The decisions we, and our ancestors made, and had made about us, fall ever further away in time and significance. It is an inverse square. Keep moving forward, and they fall further away.

The infinite game counsels us to look at where we are, see what we’ve got now and how to make the best of it. It focuses on the decisions we can influence now and the possibilities of the future. It regards the past as informational and instructive, not constraining. If I once hit my thumb with a hammer, I know to be careful next time I use a hammer. It does not make me forever a victim of hammer abuse.

Now there is one objection to this, and that is to say its premise is wrong: it rejects the causal principle on which the western enlightenment is founded. For the causal principle leads us to some kind of determinism, by which the future is, loosely or tightly, a consequence of the past.

The “tight” version is a form of data modernism. Every branch of the world ash of destiny, every atomic reaction, every operating impulse of the universe is, in principle, calculable and that we have not yet done so is down to our own feeble calculating machines. Many serious intellectuals believe this. If it is true, then everything in the future is inevitable, immutable, and there’s nothing to be gained from grousing about it.

The “loose” version still says there are better and worse ways of interacting with the world, they can be — must be — deduced objectively, that is, without reference to any person’s subjective standpoint regardless of how marginalised, and this is precisely what the social institutions standpoint theory so criticises are there to so. So, there's nothing to be gained from grousing about it.

The past as a formal system

Not also the idea that the past is a single formal causal chain, that we know about, is is a classic example of legibility in the sense articulated by James C. Scott in Seeing Like a State.

Articulation of history is necessarily a simplification, and model, a boiling down of an infinity of information into a single digestible narrative. It necessarily misses things: relegates things; deems things extraneous. But what the dominant narrative things is important and what the community thinks is important are not the same. In the same way that informal systems and interactions, unseen by the executive actors, are critical to the good order and smooth operation of the state, or a business, so are informal, unobserved, and deprioritised interactions fundamental to history. Models lie.

So not only is “the past” — as we articulate it — inert and immutable, it’s not even true. We can, and do, adjust it by changing our account of it. History is written by the winners — but it is a long game and just who is the winner is prone to change. Those who dominate the narrative from time to time decide who the winners are. This is the Orwellian concept: write and re-write and erase our history, whilst insisting on its utter continuity. It may be so that the external history of the universe is immutable — but we have no access to that. We wouldn’t recognise it even if we had it. We can only tell ourselves stories, and they have internal meaning, but no transcendent one.

See also

References

- ↑ Well, the odds are some bastard did, but not by design and not because he had any special knowledge or insight. He just happened to have his money on the horse that came in. In a random walk, among a big enough stable of runners and riders, someone will back the horse that wins.

- ↑ Unless you accept the data formalist’s stance that the universe is a clockwork, causal determinacy is absolute, and therefore the future is a linear extrapolating of the past. In which case, so is complaining about it. Nothing can be done, and no-one is to be blamed: we are “as flies to wanton boys”.