Blockbusters: Why Big Hits and Big Risks are the Future of the Entertainment Business

|

Blockbusters: Why Big Hits and Big Risks are the Future of the Entertainment Business — Anita Elberse

Contra the long tail: the fat head

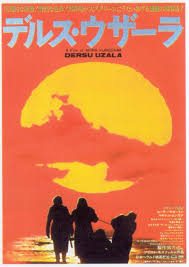

If you only see one movie a year, it’s not likely to be Dersu Uzala.[1]

If you are a movie executive, this ought not to rock your world. It certainly isn’t a function of the information revolution and would have been as true when Derzu Uzala was released in 1975 as it is today. Yet it is the intellectual cornerstone of Anita Elberse’s provocative new book “Blockbusters” — an unfortunate title, given Blockbuster’s fate, come to think of it — which dismantles that millennial canard that is Chris Anderson’s The Long Tail.

Elberse’s hook is simple: if you are a global media conglomerate, you are better off betting the farm on a small number of “blockbuster” projects than managing your margins across a diverse portfolio of smaller projects. Elberse compares Warner, who did this, with NBC TV — and latterly, I wonder, Netflix — who did not, and reaches her conclusion.

There is something of a false premise here: in plumping for yet another superhero instalment, Warner Brothers isn’t really “risking big”. Rather, it is goosing its scale, but risking small: the five films on its annual slate will all be formulaic (remakes, sequels, or new films in tried-and-true genres), will rely on well-known stars and directors and immense production resources to deliver superficial fireworks without challenging norms or demanding any great commitment from viewers. More or less, guaranteed to shift tickets: for the average punter who sees but one movie a year, this is the kind of movie it will be.

Warner targets precisely the sort of person who sees only one — or five — movies a year because that’s how many it makes.

Some all-but-self-evident assumptions:

- The marginal return on each additional movie ticket you sell tends (but never quite gets) to 100%: All other things being equal, the more people see your movie, the greater your profit margin will be.

- Most filmgoers do not see a given film more than once.

- More filmgoers see five movies a year than see 500.

- Filmgoers who see only five films in a year won’t go see Derzu Uzala.

If you take these assumptions as good then, if you have the resources, it is only sound business sense to make your movie one of the five that everyone will go and see. If you don’t, reset your priorities and your re-target demographic. But expect that your revenues will be accordingly constrained: there are only so many swine before whom to cast your pearls.

This is, as Elberse notes, of a piece with refocussing business strategies adopted by Apple, GM, Fender[2] and other resurgent business lines: don’t try to be all things to all people; clear out your inventory, figure out what you’re good at and hit that channel relentlessly. Quit wasting time at the periphery.

In other words, leave the long tail for the poor buggers who have no choice but to target it. But make no mistake: they may be lower down the food chain, but they are no less vital to your ecosystem. Without them, you could not do what you do: they discover and nurture new talent, do the research and development and build reputations of up-and-comers to the point where, for a Warner Brothers, they become safe enough to bet the house on.

Elberse’s theory asserts not that “only blockbusters should be made” but that blockbuster-sized studios should only make blockbusters: everyone should focus at the top of their own segment of their market.

This is really only sound common sense.

The question which Elberse doesn’t address is what effect this has on the statistical distribution of film budgets. If every producer applies a blockbuster strategy in its own segment, this will tend to make the head taller and fatter, and the tail skinnier and, at the limit, shorter. And so it transpires: According to the Financial Times, in 2000, 1 per cent of artists accounted for 71 per cent of pop music sales. Last year, the same proportion accounted for 77 per cent.

Perhaps Elberse’s theory, which owes nothing at all to the digital revolution, suggests the anointed few are getting smarter, and are hitting their channels more clinically than they used to. But down the tail lurks a much more interesting question: what happened? How was Chris Anderson so wrong? How is it that, all things being considered, the infinite time and choice vouchsafed by the digital revolution has led to us exercising fewer choices?

See also

References

- ↑ What do you mean, “What on earth is Dersu Uzala”? Sayeth Wikipedia, of Kurosawa’s lyrical masterpiece: “Dersu Uzala is epic in form yet intimate in scope. Set in the forests of Eastern Siberia at the turn of the century, it is a portrait of the friendship that grows between an ageing hunter and a Russian surveyor. A romantic hymn to nature and the human spirit.”

- ↑ Though Fender seems to have forgotten this since.