Mark-up

Mark-up

/mɑːk ʌp/ (n.)

|

Office anthropology™

|

1. (Brokerage): A broker’s mark-up (or mark-down) is a dealer’s way of making money: the equivalent in a principal arrangement to commission paid to an agent.

2. (~ language): A way of coding ordinary text in a way that machines can understand. This works quite well sometimes: The internet runs on hypertext mark-up language — “html”— an acquired taste but one which any fule can understand with a little patience; the fabulous MediaWiki runs on wiki mark-up, which even dear old five-thumbed Jolly Contrarian can understand — but other adventures have been less successful. There are lawyers at Linklaters who still can’t communicate unemotionally, having coded the entirety of the 2011 Equity Derivatives Definitions— remember those? No? — in Financial products Markup Language.

3. (Institutionalised pedantry): Legal mark-up is an impenetrable melange of passives, passive-aggressives, redundancies, flannel and non-sequiturs injected into a perfectly sensible contract by a perfectly tedious attorney. The sheer inscrutability of one’s mark-up is a criteria for inhouse legal team of the year.

Legal mark-up, being the fossil record of a legal negotiation between legal eagles, bears a striking similarity to a playground argument. It will start as a broad, wide-ranging, harangue; each side adopting fundamentally opposed positions largely for the sake of it, yet summoning commendable outrage at the other’s position, notwithstanding its fundamental arbitrariness.

The process of counter-sniping at idiotic, haughty positions — even if with idiotic, haughty positions — has a cleansing effect: as the blinds, battlements and barricades are gradually shot away, leaving just the serial absurdities behind, each side follows the same slow, careful process of reversal, the way one descends a rickety ladder, shouting gleefully, but with ebbing enthusiasm, as she goes. By the bottom, the debate has reduced into petulant snickering: correcting split infinitives, interposing redundancies, clarifying the already plain, helpfully particularising the general and addending the particular, all for the glum satisfaction of having had the last word , and/or words, as the case may be.

Both sides will walk away declaring victory, but silently resenting the disappointing but pragmatic middle ground they have found.

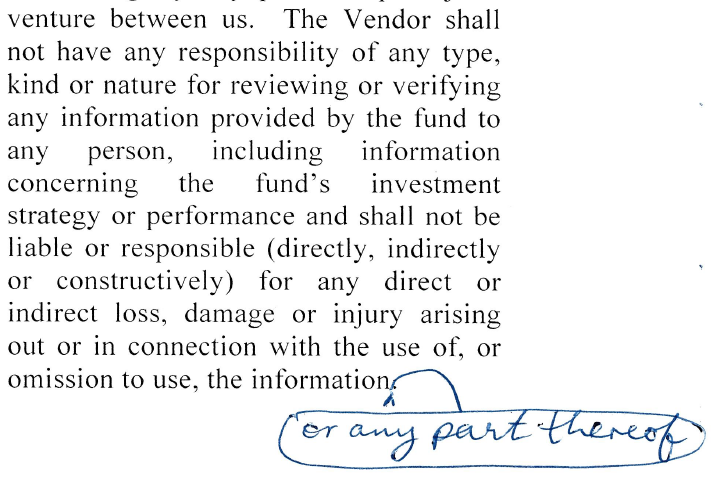

In the analogue days, mark-up found its voice in spidery handwritten annotations, balloons, glyphs and riders with which opposing lawyers would deface carefully-typed drafts. These were hard enough to decrypt in their native form, but when faxed between institutions, became quite inscrutable.[1]

Since legal employers have discovered they can and should pay their lawyers to type after all — since they can thereby dispense with legal secretaries and fax room attendants — the “manuscript mark-up” has, alas, given way to the charmless and prosaic business of running redlines.

The Biggs threshold

Any Legal markup can be situated somewhere on a “utility continuum”, between the deal-killing blockbuster, whereby a legal eagle saves her client from certain ruin, at one end, and guileless frippery, by dint of which she scrapes over her billable threshold for the month, at the other. The median point is, we need hardly say, nearer the fripperous end, but if you venture a few standard deviations past that, you approach an absolute theoretical minimum, beyond which the utility of any legal mark-up is utterly nil. That final, infinitesimal point, past which the thinnest atomic strand of half-hearted value can be no further reduced — the so-called “Biggs constant” — was first isolated in 1997 when, either by deliberate design or happy accident, a gentleman from the in-house team at a leading financial services institution found it while marking up a pricing supplement he had received by fax. From me. Despite the Byzantine complexity of the document, his only comment was a direction to his diligent counsel — yours truly — to remove the bold formatting from a full stop. This he communicated, also by fax, at 2:35 in the morning. In the kind of irony that accompanies so many of the world’s most momentous occasions, it turned out upon inspection that the full stop wasn’t bold in the first place, but was a printed artefact from the low resolution of the fax.

See also

References

- ↑ The process was not without its serendipities: the Biggs hoson was discovered this way.