Breakage costs

|

Banking basics

A recap of a few things you’d think financial professionals ought to know

|

Breakage costs

/ˈbreɪkɪdʒ kɒsts/ (n.)

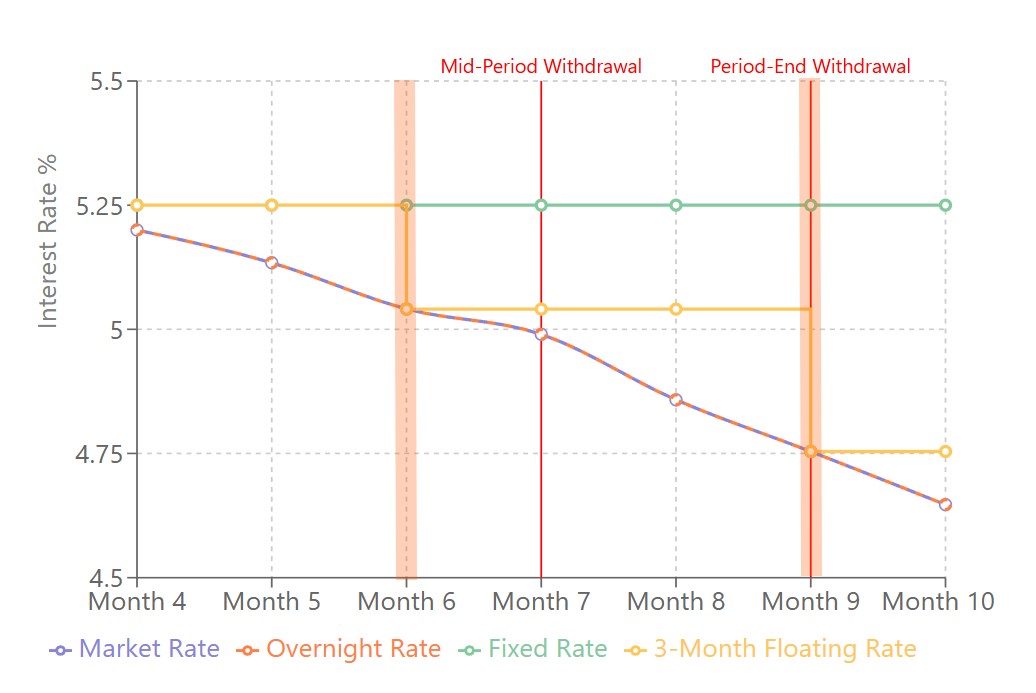

Breakage costs arise because a lender of money for a fixed term is exposed to changes in interest rates over that term. It will have — can be assumed to have — hedged the interest rate risk of providing those funds to the end of the committed period, so if it has to unwind its interest rate hedges beforehand to repay the money, it may make a gain or loss.

The size of interest rate breakage costs will therefore be a function of (i) how far the prevailing market rates have moved since the contract rate was set, and (ii) how much time remains to the end of the present fixed commitment period. There will be often be a “hump”: breakage costs will tend to increase as the market rate diverges from the fixed rate (on day 1 they will be the same) then decrease again as the number of days remaining in the fixed term period (by which the increasing differential is multiplied) diminishes to zero.

The breakage costs on a 5-year fixed period on a mortgage loan are therefore, potentially large, which is why it is so expensive to repay a fixed mortgage early. The breakage costs on loan that resets its interest every month (a floating rate loan) will be much smaller. The breakage costs on overnight deposits will be, by definition, nil.

Swap break costs

The same principle holds for swap break costs, only the comparison will be the prevailing market rate for the reference asset against its value when the swap was executed (its “strike price”).

On the trade date an asset’s strike place and its market price are, Q.E.D., the same. On any other day swap break costs will generally be simply the breakage cost of the asset leg, payable one way, less the breakage costs of the financing leg, payable the other. The financing leg is explicitly an interest rate breakage cost; the asset break is by analogy one. In each case, the same “time decay” effect and “duration hump” effect should be in play.