Conspicuous: Difference between revisions

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| (23 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{a|plainenglish| | |||

{{image|Freddie Mercury Conspicuous|png|}} | |||

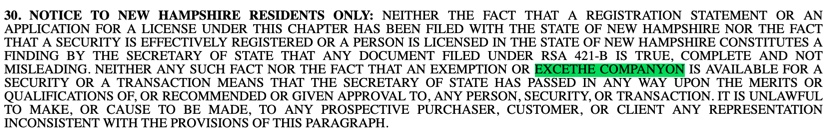

{{image|New Hampshire typo|jpg|Not [[conspicuous]] enough for the proof-readers, apparently. We are going to hazard the guess that this tract was carelessly marked up off the PIMCO Tactical Income Fund prospectus.}} | |||

}}A brief unqualified note to shed light on WHY AMERICANS LIKE TO SPRAY THEIR LEGAL DOCUMENTS WITH LARGE SWATHES OF TEXT IN CAPITALS. | |||

IT ''ISN’T'' BECAUSE AMERICANS LIKE TO SHOUT ALL THE TIME — THOUGH OUR UNSCIENTIFIC OBSERVATIONS ON THIS TOPIC SUGGEST THAT THEY ''DO'' LIKE TO SHOUT ALL THE TIME, ESPECIALLY AT [[New Hampshire|RESIDENTS OF NEW HAMPSHIRE]], BUT BECAUSE, SO AMERICAN LAWYERS HAVE BEEN CONDITIONED TO THINK, THE [[UCC|UNIFORM COMMERCIAL CODE]] REQUIRES EVERYTHING TO BE IN CAPITALS FOR THOSE TERMS THAT THE CODE REQUIRES TO BE “[[CONSPICUOUS]]” ENOUGH THAT A REASONABLE BADGER AGAINST WHICH THE TERMS IN QUESTION ARE EXPECTED TO OPERATE OUGHT TO HAVE NOTICED THEM. | |||

But “[[conspicuous]]” ''doesn’t'' mean block capitals. | |||

The [[Uniform Commercial Code]] defines it thus: | |||

{{ | ''“[[Conspicuous]]”, with reference to a term, means so written, displayed, or presented that a reasonable person against which it is to operate ought to have noticed it. Whether a term is “[[conspicuous]]” or not is a decision for the court. [[Conspicuous]] terms [[including but not limited to|include]] the following: (A) a heading in [[CAPS LOCK|capitals]] equal to or greater in size than the surrounding text, [[or]] in contrasting type, font, or color to the surrounding text of the same or lesser size; [[and]] (B) language in the body of a record or display in larger type than the surrounding text, [[or]] in contrasting type, font, or color to the surrounding text of the same size, [[or]] set off from surrounding text of the same size by symbols or other marks that call attention to the language. | ||

And the judiciary have thrown in their dime: | |||

:“[[legal eagle|Lawyers]] who think their [[CAPS LOCK|caps lock]] keys are instant ‘make [[conspicuous]]’ buttons are deluded. In determining whether a term is [[conspicuous]], we look at more than formatting. [...] '''A sentence in capitals, buried deep within a long paragraph in [[capitals]] will probably not be [[deemed]] [[conspicuous]].''' Formatting does matter, but conspicuousness ultimately turns on the likelihood that a [[reasonable person]] would actually see a term in an agreement. '''''Thus, it is entirely possible for text to be [[conspicuous]] without being in capitals'''''.” <ref>''[[In Re Bassett - Case Note|In Re Bassett]]'', 285 F.3d 882, 886 (9th Cir. 2002) (''Conspicuity added'')</ref> | |||

Now it is well-established in the literature that text in all caps is ''harder'' to read than ordinary text, so you might form your own opinion as to what possesses securities lawyers to render acres of their prospectuses in a less legible way — so less legible that even their own proof-readers have trouble catching every nuance, as the example from US Nuclear Corp’s [[offering memorandum]], in the panel, illustrates. | |||

On the other hand — and this is drawn from the [[JC]]’s theory of [[purpose]] in [[legal eagle]]ry, by the way — the point at which it matters whether a term is conspicuous is ''before one makes the decision to execute'', and the person by whom its reasonable conspicuity is to be judged is the person who realistically will be reading it. Afterwards, it is too late: whatever the term, as soon as it is germane, you may be assured its beneficiary will, gleefully, bring it to your attention. When you need it to be conspicuous is at the point where you are agreeing to it. If you have delegated the task of reading the contract to an agent, then what matters is not whether you would notice the clause, but whether your agent would. | |||

So, if the passage in question appears only on page 406 of an [[information memorandum]] relating to [[Wickliffe Hampton]]’s TRL300,000,000,000,000 26⅔% Subordinated Convertible Credit-Linked Bonds Due 4035 then, we humbly submit, there is ''no'' typographical contrivance in existence — or even possible in the realms of plausible science fiction, for that matter — that could be “so written, displayed, or presented that a reasonable person against which it is to operate ought to have noticed it” since ''there is not a reasonable person alive who reads past the first five pages of an information memorandum anyway''. | |||

On the other hand, should the passage be buried in the sort of document that, by market convention, legal eagles from all sides will examine and critique — and draft bilateral contracts in the financial services world are ''exactly'' such documents, — then there is no chance that a reasonable person<ref>The reasonable reader here is not the counterparty to the contract, but the legal counsel it has engaged to {{strike|gorge themselves on the contract’s verbosity|review the contract}}</ref> — [[legal eagles]] are ''[[implicitly]]'' “reasonable” readers — would miss it. A lawyer who doesn’t notice part of a draft, however small the font in which it is rendered, is, [[Q.E.D.]], ''[[negligent]]'', which is, [[Q.E.D.]], ''un''reasonable. | |||

P.S. Did you notice the ''badger'' in the above capitalised text? No? Fancy that. | |||

{{sa}} | |||

*''[[In Re Bassett - Case Note|In Re Bassett]]'' | |||

*The eminently shoutable-at, and oft-shouted at, people of [[New Hampshire]] | |||

*[[Purpose]] | |||

*[[Key information document]] | |||

{{ref}} | |||

Revision as of 14:42, 9 July 2024

|

Towards more picturesque speech™

|

A brief unqualified note to shed light on WHY AMERICANS LIKE TO SPRAY THEIR LEGAL DOCUMENTS WITH LARGE SWATHES OF TEXT IN CAPITALS.

IT ISN’T BECAUSE AMERICANS LIKE TO SHOUT ALL THE TIME — THOUGH OUR UNSCIENTIFIC OBSERVATIONS ON THIS TOPIC SUGGEST THAT THEY DO LIKE TO SHOUT ALL THE TIME, ESPECIALLY AT RESIDENTS OF NEW HAMPSHIRE, BUT BECAUSE, SO AMERICAN LAWYERS HAVE BEEN CONDITIONED TO THINK, THE UNIFORM COMMERCIAL CODE REQUIRES EVERYTHING TO BE IN CAPITALS FOR THOSE TERMS THAT THE CODE REQUIRES TO BE “CONSPICUOUS” ENOUGH THAT A REASONABLE BADGER AGAINST WHICH THE TERMS IN QUESTION ARE EXPECTED TO OPERATE OUGHT TO HAVE NOTICED THEM.

But “conspicuous” doesn’t mean block capitals.

The Uniform Commercial Code defines it thus:

“Conspicuous”, with reference to a term, means so written, displayed, or presented that a reasonable person against which it is to operate ought to have noticed it. Whether a term is “conspicuous” or not is a decision for the court. Conspicuous terms include the following: (A) a heading in capitals equal to or greater in size than the surrounding text, or in contrasting type, font, or color to the surrounding text of the same or lesser size; and (B) language in the body of a record or display in larger type than the surrounding text, or in contrasting type, font, or color to the surrounding text of the same size, or set off from surrounding text of the same size by symbols or other marks that call attention to the language.

And the judiciary have thrown in their dime:

- “Lawyers who think their caps lock keys are instant ‘make conspicuous’ buttons are deluded. In determining whether a term is conspicuous, we look at more than formatting. [...] A sentence in capitals, buried deep within a long paragraph in capitals will probably not be deemed conspicuous. Formatting does matter, but conspicuousness ultimately turns on the likelihood that a reasonable person would actually see a term in an agreement. Thus, it is entirely possible for text to be conspicuous without being in capitals.” [1]

Now it is well-established in the literature that text in all caps is harder to read than ordinary text, so you might form your own opinion as to what possesses securities lawyers to render acres of their prospectuses in a less legible way — so less legible that even their own proof-readers have trouble catching every nuance, as the example from US Nuclear Corp’s offering memorandum, in the panel, illustrates.

On the other hand — and this is drawn from the JC’s theory of purpose in legal eaglery, by the way — the point at which it matters whether a term is conspicuous is before one makes the decision to execute, and the person by whom its reasonable conspicuity is to be judged is the person who realistically will be reading it. Afterwards, it is too late: whatever the term, as soon as it is germane, you may be assured its beneficiary will, gleefully, bring it to your attention. When you need it to be conspicuous is at the point where you are agreeing to it. If you have delegated the task of reading the contract to an agent, then what matters is not whether you would notice the clause, but whether your agent would.

So, if the passage in question appears only on page 406 of an information memorandum relating to Wickliffe Hampton’s TRL300,000,000,000,000 26⅔% Subordinated Convertible Credit-Linked Bonds Due 4035 then, we humbly submit, there is no typographical contrivance in existence — or even possible in the realms of plausible science fiction, for that matter — that could be “so written, displayed, or presented that a reasonable person against which it is to operate ought to have noticed it” since there is not a reasonable person alive who reads past the first five pages of an information memorandum anyway.

On the other hand, should the passage be buried in the sort of document that, by market convention, legal eagles from all sides will examine and critique — and draft bilateral contracts in the financial services world are exactly such documents, — then there is no chance that a reasonable person[2] — legal eagles are implicitly “reasonable” readers — would miss it. A lawyer who doesn’t notice part of a draft, however small the font in which it is rendered, is, Q.E.D., negligent, which is, Q.E.D., unreasonable.

P.S. Did you notice the badger in the above capitalised text? No? Fancy that.

See also

- In Re Bassett

- The eminently shoutable-at, and oft-shouted at, people of New Hampshire

- Purpose

- Key information document

References

- ↑ In Re Bassett, 285 F.3d 882, 886 (9th Cir. 2002) (Conspicuity added)

- ↑ The reasonable reader here is not the counterparty to the contract, but the legal counsel it has engaged to

gorge themselves on the contract’s verbosityreview the contract