Bright-line test: Difference between revisions

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) No edit summary Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| (14 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

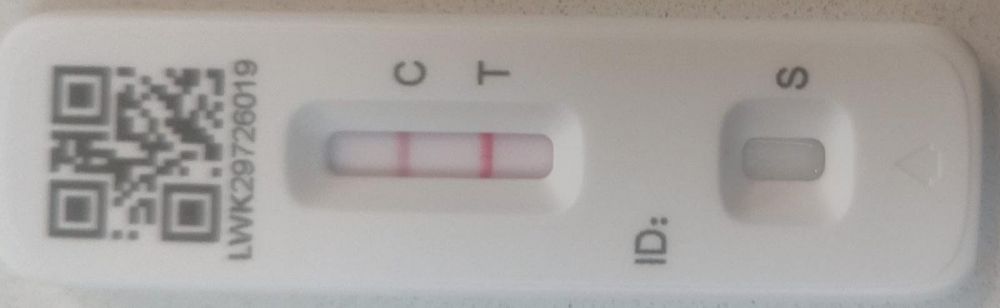

{{ | {{a|g|{{image|Bright Line Test|jpg|I told you I was ill.}}}}{{d|Bright-line test|/brʌɪt lʌɪn tɛst/|n|}} | ||

(''American''). A conceptual exercise bestowing so great a degree of confidence in the mind of a [[U.S. Attorney|member of the New York bar]] that it cannot, as a matter of [[metaphysics|metaphysical]] theory (much less ''legal'' theory) exist. A bright-line test is therefore a [[paradox]]; a kind of unachievable [[Platonic form]]; a sunlit upland to which all [[U.S. attorney]]s wistfully aspire, but which all know, and thank their lucky stars, they will never have to encounter in person. | |||

Wikipedia tells us the “bright-line test” originates in U.S. constitutional law, where the founding fathers held it to be a self-evident truth that overly simplistic “bright-line” rules had such great potential to unjustly deprive U.S. attorneys of their 9th Amendment rights to filibuster indefinitely for the account, if not the benefit, of their clients without arriving at a useful conclusion that the courts were justified in striking down any such rules that anyone might contrive to enact. | |||

In a lengthy disquisition, Supreme Court Justice Jefferson D. Hogg observed that “no single set of principles can ever capture or limit the ever-shifting complexity of an attorney’s discursions.” | |||

Thus, the words “[[bright-line test]]” are always uttered in the negative, and with insincere remorse — e.g., “sadly, there’s no [[bright-line test]] for this”. The logical impossibility of a bright-line test is a [[US attorney]]’s means of evading any responsibility for anything she says, does, or commits to a lengthy written [[legal opinion|memorandum of advice]]. | |||

===Usage=== | ===Usage=== | ||

| Line 6: | Line 13: | ||

{{sa}} | {{sa}} | ||

*[[You would say that]] | |||

*[[Doubt]] | |||

*[[Chicken licken]] | *[[Chicken licken]] | ||

*[[US Attorney]] | *[[US Attorney]] | ||

{{c|Paradox}} | |||

{{Friday Philosophy|15/1/21}} | |||

Latest revision as of 22:00, 12 November 2022

|

Bright-line test

/brʌɪt lʌɪn tɛst/ (n.)

(American). A conceptual exercise bestowing so great a degree of confidence in the mind of a member of the New York bar that it cannot, as a matter of metaphysical theory (much less legal theory) exist. A bright-line test is therefore a paradox; a kind of unachievable Platonic form; a sunlit upland to which all U.S. attorneys wistfully aspire, but which all know, and thank their lucky stars, they will never have to encounter in person.

Wikipedia tells us the “bright-line test” originates in U.S. constitutional law, where the founding fathers held it to be a self-evident truth that overly simplistic “bright-line” rules had such great potential to unjustly deprive U.S. attorneys of their 9th Amendment rights to filibuster indefinitely for the account, if not the benefit, of their clients without arriving at a useful conclusion that the courts were justified in striking down any such rules that anyone might contrive to enact.

In a lengthy disquisition, Supreme Court Justice Jefferson D. Hogg observed that “no single set of principles can ever capture or limit the ever-shifting complexity of an attorney’s discursions.”

Thus, the words “bright-line test” are always uttered in the negative, and with insincere remorse — e.g., “sadly, there’s no bright-line test for this”. The logical impossibility of a bright-line test is a US attorney’s means of evading any responsibility for anything she says, does, or commits to a lengthy written memorandum of advice.

Usage

“There is no bright line test in the rules, and consequently there is always a potential risk that regulators might be inclined to take the view that your good faith practice on which your firm designed its SOX implementation might not be recharacterized as a safe harbor to Title III of Regulation G of Rule 14-a7 of the ’40 Act ...” zzzzz zzzz zzzz HEY! WAKE UP!