David Lange: My Life: Difference between revisions

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) m Amwelladmin moved page David Lange: My Life - Book Review to David Lange: My Life |

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| (7 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

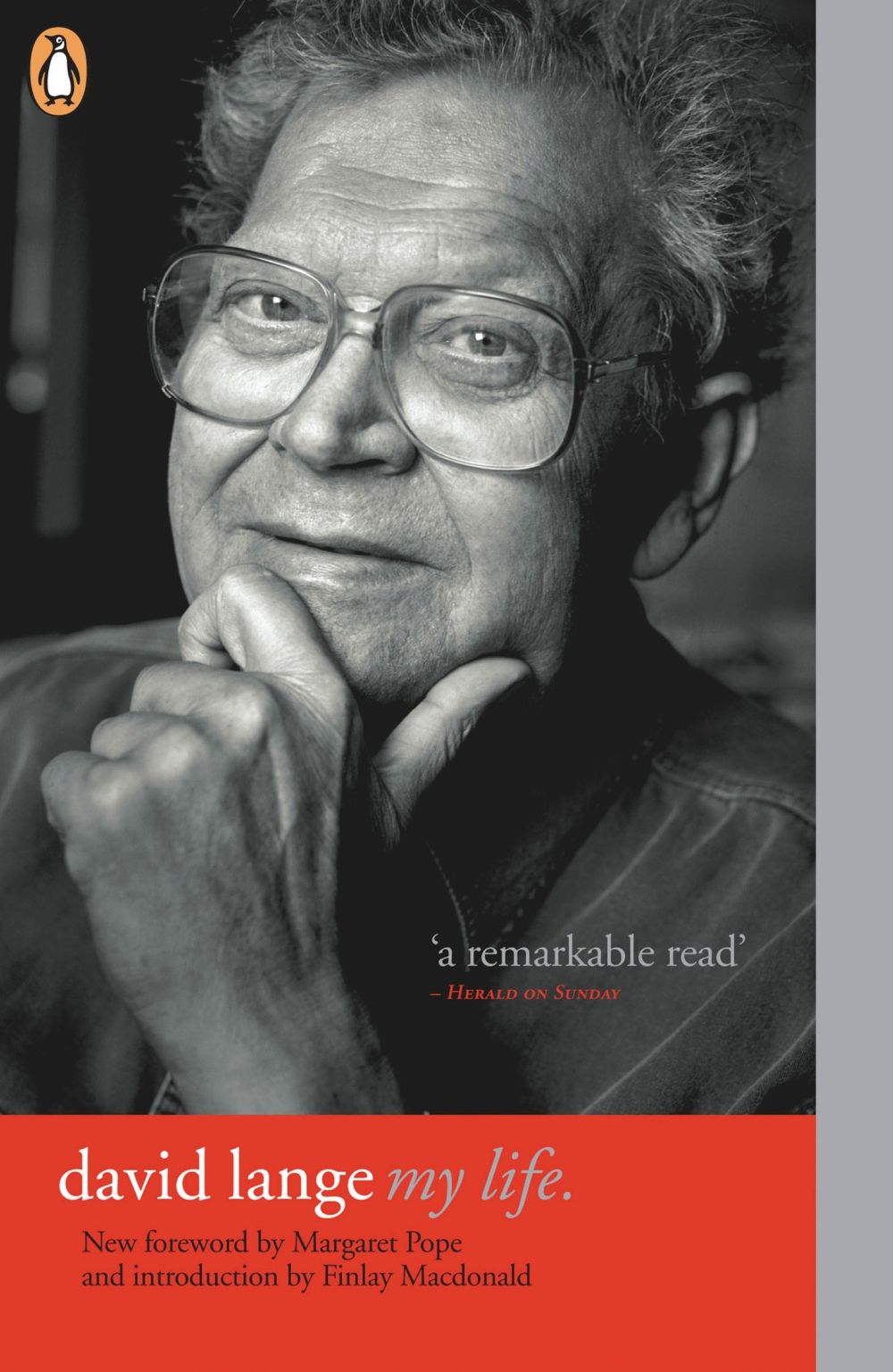

{{A|book review|}}{{br|My Life}} | {{A|book review|{{image|David Lange|jpg|}}}}{{br|David Lange: My Life}} — | ||

{{author|David Lange}}<br> | {{author|David Lange}}<br> | ||

''Review first published 3 November 2007'' | ''Review first published 3 November 2007'' | ||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

One might have reservations about his politics and the trajectory of his carriage of public office, but it is impossible to deny the impact [[David Lange]] and his fourth Labour government had on New Zealand society, nor his eloquence as a public speaker and raconteur. When Lange died of complications from renal failure last year New Zealand lost a unique voice and left no obvious successor. | One might have reservations about his politics and the trajectory of his carriage of public office, but it is impossible to deny the impact [[David Lange]] and his fourth Labour government had on New Zealand society, nor his eloquence as a public speaker and raconteur. When Lange died of complications from renal failure last year New Zealand lost a unique voice and left no obvious successor. | ||

This short autobiographical memoir - dictated in his last days, as his eyesight gave out and he could no longer read or write, is a wonderful book. | This short autobiographical memoir - dictated in his last days, as his eyesight gave out and he could no longer read or write, is a wonderful book. Lange’s prose is wonderful in the early stages — benefitting, I think, from how he delivered the manuscript (you can almost hear it as an extempore public address) — and there is something sombre and moving about the way, as the chapters progress, the fluidity dries up, a function of Lange’s failing health and ebbing energy. | ||

David Lange died two days after the final proofs rolled from the presses. | David Lange died two days after the final proofs rolled from the presses. | ||

Not only beautifully crafted | Not only beautifully crafted but historically interesting too: clearly (and unashamedly) coloured by Lange’s own perspective, it is a useful prism for viewing the directions in which Lange pulled his administration, which at the time defied easy explanation. Lange is candid about the deterioration of his relationship with co-architect Roger Douglas, and magnanimous enough to recognise that their long-lasting rancour was due as much to his own intemperate personality as Douglas’ uncompromising vision. | ||

I dare say that | I dare say that Douglas’ memoir of the same period, should he write one (and I hope he does) will provide a somewhat different and equally valuable picture of events. | ||

====Wage and Price Freeze==== | |||

Lange validates one extraordinary episode. In June 1982, faced with rampant inflation brought about by years of interventionist economic mismanagement — much of it his own — [[New Zealand]] Prime Minister [[Robert Muldoon]] bet the farm (''literally'': in 1982, [[New Zealand]] was one big farm, with 70 million sheeple. I mean sheep. In fact, 1982 was peak sheep for [[New Zealand]], with 70.3 million of the buggers)<ref>These days, there are 29.5 million, according to [http://archive.stats.govt.nz/browse_for_stats/population/mythbusters/3million-people-60million-sheep.aspx NZ’s official statistics folk].</ref> on the most radical intervention a guy could make short of nationalising the means of production altogether: He ''banned'' inflation. By executive fiat, Muldoon announced a total [[wage and price freeze]]. Henceforth it would be ''illegal'' to increase wages or prices in [[New Zealand]].<ref>Where was the Minister of Finance in all of this, you might ask? Right there. “Chairman and CEO” Robert Muldoon was the Minister of Finance, too.</ref> | |||

Overnight, he said, inflation would be fixed! Easy, right? Things stayed this way for two and a half years until Muldoon was, at last, thrown out of office, after incautiously calling a snap election when drunk. By this time the economy was so demoralised [[David Lange|Lange]]’s incoming Labour government had no choice but to implement the sweeping reforms the economy needed, announcing an immediate twenty per cent devaluation in the pegged New Zealand Dollar. | |||

But Muldoon — still caretaker prime minister, pending the swearing-in of the new government, was not done with his wrecking. He promptly precipitated a constitutional crisis — and a dramatic run on the [[New Zealand dollar]] — by publicly refusing the new administration’s instruction to devalue the [[Kiwi]]. There was so little money left that Lange instructed New Zealand’s international diplomatic staff around the world to ''max out their credit cards'' so there would be money to pay the bills. | |||

A few years on, with plenty of hindsight and more wounds healed by time, this might yet — without | {{quote|“We actually were reduced to asking our diplomatic posts abroad how much money they could draw down on their credit cards! That is the extent of the calamity that had been ground into us by the briefings that we’d got.”<ref>Marcia Russell, ''Revolution: New Zealand from Fortress to Free Market''.(1996)</ref>}} | ||

====In the end==== | |||

Ultimately the Lange administration will be seen in the wider geopolitical context of the 1980s perhaps as something that was going to happen at some point anyway, but when one looks at the vibrant, dynamic and diverse culture, economy and polity that New Zealand enjoys today, and compare it with the staid and stultifying one which Lange took on in 1984, one can only tip one’s hat to the man who actually did start that process rolling and acknowledge this very personal record of the events. | |||

In 1984 Lange’s soon-to-be predecessor, the late unlamented [[Robert Muldoon|Rob Muldoon]], left a sarcastic epitaph, reflexively, in the course of being pasted in a televised political debate: when stumped for anything to else say at all, barked bitterly: “I love you, Mister Lange.” | |||

A few years on, with plenty of hindsight and more wounds healed by time, this might yet — without Muldoon’s ironic veneer — grow to be the received wisdom about David Russell Lange’s contribution to New Zealand’s political history. | |||

{{sa}} | {{sa}} | ||

*[[Robert Muldoon]] | *[[Robert Muldoon]] | ||

*[[Wage and price freeze]] | *[[Wage and price freeze]] | ||

{{ref}} | |||

Latest revision as of 16:12, 6 March 2024

|

David Lange: My Life —

David Lange

Review first published 3 November 2007

Fascinating insight into a gifted, complex and influential New Zealand politician

One might have reservations about his politics and the trajectory of his carriage of public office, but it is impossible to deny the impact David Lange and his fourth Labour government had on New Zealand society, nor his eloquence as a public speaker and raconteur. When Lange died of complications from renal failure last year New Zealand lost a unique voice and left no obvious successor.

This short autobiographical memoir - dictated in his last days, as his eyesight gave out and he could no longer read or write, is a wonderful book. Lange’s prose is wonderful in the early stages — benefitting, I think, from how he delivered the manuscript (you can almost hear it as an extempore public address) — and there is something sombre and moving about the way, as the chapters progress, the fluidity dries up, a function of Lange’s failing health and ebbing energy.

David Lange died two days after the final proofs rolled from the presses.

Not only beautifully crafted but historically interesting too: clearly (and unashamedly) coloured by Lange’s own perspective, it is a useful prism for viewing the directions in which Lange pulled his administration, which at the time defied easy explanation. Lange is candid about the deterioration of his relationship with co-architect Roger Douglas, and magnanimous enough to recognise that their long-lasting rancour was due as much to his own intemperate personality as Douglas’ uncompromising vision.

I dare say that Douglas’ memoir of the same period, should he write one (and I hope he does) will provide a somewhat different and equally valuable picture of events.

Wage and Price Freeze

Lange validates one extraordinary episode. In June 1982, faced with rampant inflation brought about by years of interventionist economic mismanagement — much of it his own — New Zealand Prime Minister Robert Muldoon bet the farm (literally: in 1982, New Zealand was one big farm, with 70 million sheeple. I mean sheep. In fact, 1982 was peak sheep for New Zealand, with 70.3 million of the buggers)[1] on the most radical intervention a guy could make short of nationalising the means of production altogether: He banned inflation. By executive fiat, Muldoon announced a total wage and price freeze. Henceforth it would be illegal to increase wages or prices in New Zealand.[2]

Overnight, he said, inflation would be fixed! Easy, right? Things stayed this way for two and a half years until Muldoon was, at last, thrown out of office, after incautiously calling a snap election when drunk. By this time the economy was so demoralised Lange’s incoming Labour government had no choice but to implement the sweeping reforms the economy needed, announcing an immediate twenty per cent devaluation in the pegged New Zealand Dollar.

But Muldoon — still caretaker prime minister, pending the swearing-in of the new government, was not done with his wrecking. He promptly precipitated a constitutional crisis — and a dramatic run on the New Zealand dollar — by publicly refusing the new administration’s instruction to devalue the Kiwi. There was so little money left that Lange instructed New Zealand’s international diplomatic staff around the world to max out their credit cards so there would be money to pay the bills.

“We actually were reduced to asking our diplomatic posts abroad how much money they could draw down on their credit cards! That is the extent of the calamity that had been ground into us by the briefings that we’d got.”[3]

In the end

Ultimately the Lange administration will be seen in the wider geopolitical context of the 1980s perhaps as something that was going to happen at some point anyway, but when one looks at the vibrant, dynamic and diverse culture, economy and polity that New Zealand enjoys today, and compare it with the staid and stultifying one which Lange took on in 1984, one can only tip one’s hat to the man who actually did start that process rolling and acknowledge this very personal record of the events.

In 1984 Lange’s soon-to-be predecessor, the late unlamented Rob Muldoon, left a sarcastic epitaph, reflexively, in the course of being pasted in a televised political debate: when stumped for anything to else say at all, barked bitterly: “I love you, Mister Lange.”

A few years on, with plenty of hindsight and more wounds healed by time, this might yet — without Muldoon’s ironic veneer — grow to be the received wisdom about David Russell Lange’s contribution to New Zealand’s political history.

See also

References

- ↑ These days, there are 29.5 million, according to NZ’s official statistics folk.

- ↑ Where was the Minister of Finance in all of this, you might ask? Right there. “Chairman and CEO” Robert Muldoon was the Minister of Finance, too.

- ↑ Marcia Russell, Revolution: New Zealand from Fortress to Free Market.(1996)