Correlation: Difference between revisions

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) No edit summary Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

[[All other things being equal]], a [[correlation]] is more likely to evidence a [[causation]] than a ''lack'' of correlation, right? This is one of those logical canards, as Monty Python put it, “[[universal affirmative]]s can only be partially converted: all of Alma Cogan is dead, but only some of the class of dead people are Alma Cogan.” | [[All other things being equal]], a [[correlation]] is more likely to evidence a [[causation]] than a ''lack'' of correlation, right? This is one of those logical canards, as Monty Python put it, “[[universal affirmative]]s can only be partially converted: all of Alma Cogan is dead, but only some of the class of dead people are Alma Cogan.” | ||

So here’s the thing, and I am straining to avoid distracting myself onto my pet subjects of transcendent truth and causal skepticism, so bear with me: | |||

Even if you accept some objectivist model where, whether we can know it or not, there ''is'' a true, unique, cause for every effect — and down that rabbit hole are a bunch of consequences you really wouldn’t like, but let’s say — it follows that an event can have but one cause, or causal matrix, to the absolute exclusion of any other explanation. That is to say, for every single true cause, there are multiple [[spurious correlation]]s — events that serendipitously ''seem'', by their statistical regularity, to have causal significance, but in fact don’t. | |||

How many is “multiple”? ''Depends on how much data, and how much imagination, you’ve got''. Seeing as [[the portion of all data we have collected is nil]], the actual answer is that ''there are infinitely more spurious correlations than there are true ones''. The likelihood that any given correlation is the true cause is 1/∞, which is ''zero''. | |||

Revision as of 09:04, 17 October 2020

|

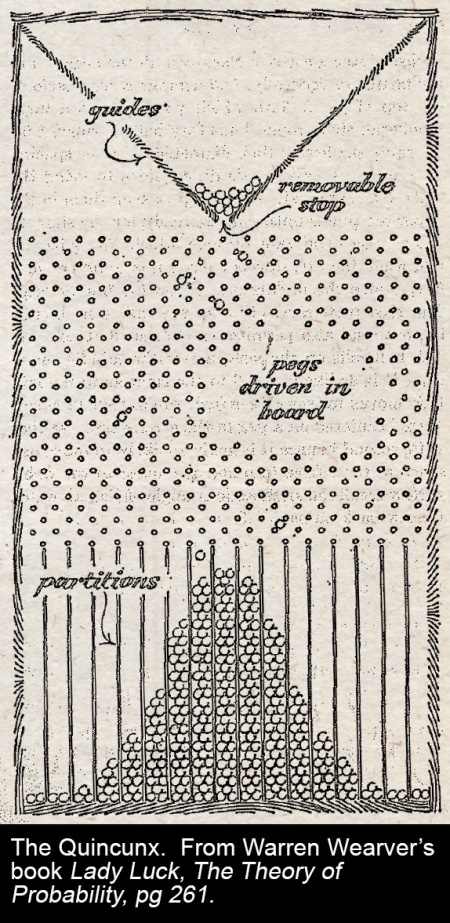

The idea, following from Sir Francis Galton’s experiments with a quincunx and first articulated by statistician Karl Pearson[1] that a relationship between two variables could be characterised according to its statistical strength and expressed in numbers, regardless of any perceived causal connection between them.

If one can derive significance from a purely statistical correlation without a deeper mechanical theory of the universe that might tell us why, we are well on our way to an artificially intelligent future where robots can wipe elderly arses, all bankers are redundant (good, right?), so is everyone else (not so good?) and it is only a matter of time before Skynet becomes self-aware and starts hunting down random skater kids from the 1990s.

If.

But, in some cases you can derive a significance; in some cases you can’t[2] but — irony upcoming — without a sophisticated theory of causality, it will be hard to tell them apart. That is to say, a bare correlation won’t tell you whether there is a causal arrow at all, much less — if there is — which way it flows.

“Correlation”[3] ought to be a synonym for “mere coincidence”[4] though in its more fashionable usages, especially among big data freaks, this tends to get — well — buried in the noise. There may be something profound, reflexive and ironic about this, but it’s too early in the morning to figure out out. At any rate, the more data you have the, the worse your signal, and the more chanting “correlation does not imply causation” in a sing-song voice whenever anyone cites a correlation will annoy the hell out of big data freaks — which is all the more reason to do it.

Correlation and causation

Now it is true that correlation doesn’t imply causation, but it doesn’t rule it out either. And it is certainly true that a lack of correlation does imply a lack of causation.

All other things being equal, a correlation is more likely to evidence a causation than a lack of correlation, right? This is one of those logical canards, as Monty Python put it, “universal affirmatives can only be partially converted: all of Alma Cogan is dead, but only some of the class of dead people are Alma Cogan.”

So here’s the thing, and I am straining to avoid distracting myself onto my pet subjects of transcendent truth and causal skepticism, so bear with me:

Even if you accept some objectivist model where, whether we can know it or not, there is a true, unique, cause for every effect — and down that rabbit hole are a bunch of consequences you really wouldn’t like, but let’s say — it follows that an event can have but one cause, or causal matrix, to the absolute exclusion of any other explanation. That is to say, for every single true cause, there are multiple spurious correlations — events that serendipitously seem, by their statistical regularity, to have causal significance, but in fact don’t.

How many is “multiple”? Depends on how much data, and how much imagination, you’ve got. Seeing as the portion of all data we have collected is nil, the actual answer is that there are infinitely more spurious correlations than there are true ones. The likelihood that any given correlation is the true cause is 1/∞, which is zero.

See also

- In God we trust, all others must bring data

- Contractual causation

- The Book of Why: The New Science of Cause and Effect by Judea Pearl

References

- ↑ So Slate Magazine argues, at any rate.

- ↑ There are whole websites devoted to spurious correlations. Like, well, http://www.spuriouscorrelations.com.

- ↑ “A mutual relationship or connection between two or more things.”

- ↑ “A remarkable concurrence of events or circumstances without apparent causal connection”.