Asymptotic safety: Difference between revisions

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) No edit summary Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) No edit summary Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

The [[Biggs hoson]] is the threshold in legal markup theory of ''[[lexophysics]]'' beyond which any proposed amendment is ''syntactically'' safe: it cannot make any legal or commercial difference to the arrangements, but has enough formal significance so as not to be completely humiliating to ask for it, meaning that counsel can supplement what would otherwise be a meagre living entertaining such fripperies in the name of professionalism and commitment to the craft. So, checking [[football team]]s for punctuation, inserting [[counterparts]] clauses, preparing closing agendas and bible tables of contents and, in Biggs’ famous example, removing the bold from a [[full stop]]. | The [[Biggs hoson]] is the threshold in legal markup theory of ''[[lexophysics]]'' beyond which any proposed amendment is ''syntactically'' safe: it cannot make any legal or commercial difference to the arrangements, but has enough formal significance so as not to be completely humiliating to ask for it, meaning that counsel can supplement what would otherwise be a meagre living entertaining such fripperies in the name of professionalism and commitment to the craft. So, checking [[football team]]s for punctuation, inserting [[counterparts]] clauses, preparing closing agendas and bible tables of contents and, in Biggs’ famous example, removing the bold from a [[full stop]]. | ||

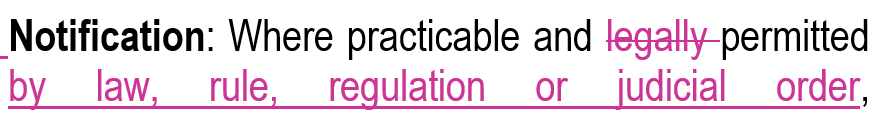

Even beyond ''totally'' pointless amendments, there are certain mark-up techniques that approach “asymptotic safety” as Weinberg envisaged it — they are not ''logically'' safe, but are ''practically'' safe — the events so far down the probability tail that, if they come about, no-one will think to blame the person drafting for unwanted consequence. So, [[entire agreement]] clauses, [[no oral modification]] provisions, [[force majeure]] elaborations; doubt avoidance. | Even beyond ''totally'' pointless amendments, there are certain mark-up techniques that approach “asymptotic safety” as Weinberg envisaged it — they are not ''logically'' safe, but are ''practically'' safe — the events so far down the probability tail that, if they come about, no-one will think to blame the person drafting for unwanted consequence. So, [[entire agreement]] clauses, [[no oral modification]] provisions, [[force majeure]] elaborations; [[for the avoidance of doubt|doubt avoidance]], and — as in the illustrated panel — a good hearty blizzard of nouns and adjectives to stand in for words like “legally”. | ||

We shouldn’t laugh: this penumbra of practically but not theoretical safety vouches safe an entire industry of [[AI]]-powered [[NDA]] reading [[legaltech]] offerings. And where would be without them? | |||

Don’t answer that. | |||

{{sa}} | {{sa}} | ||

*[[Biggs hoson]] | *[[Biggs hoson]] | ||

*[[Counterparts]] | *[[Counterparts]] | ||

Latest revision as of 12:38, 2 February 2023

|

A third option, asymptotically safe gravity, goes back still further, to 1976. It was suggested by physicist Steven Weinberg, one of the Standard Model’s chief architects. A natural way to develop a theory of quantum gravity is to add gravitons to the model. Unfortunately, this approach got nowhere, because when the interactions of the putative particles were calculated at higher energies, the maths seemed to become nonsensical. However, Weinberg, who died in July, argued that this apparent breakdown would go away (in maths speak, the calculations would be “asymptotically safe”) if sufficiently powerful machines were used to do the calculating.

- —The Economist, 28 August 2021

The Biggs hoson is the threshold in legal markup theory of lexophysics beyond which any proposed amendment is syntactically safe: it cannot make any legal or commercial difference to the arrangements, but has enough formal significance so as not to be completely humiliating to ask for it, meaning that counsel can supplement what would otherwise be a meagre living entertaining such fripperies in the name of professionalism and commitment to the craft. So, checking football teams for punctuation, inserting counterparts clauses, preparing closing agendas and bible tables of contents and, in Biggs’ famous example, removing the bold from a full stop.

Even beyond totally pointless amendments, there are certain mark-up techniques that approach “asymptotic safety” as Weinberg envisaged it — they are not logically safe, but are practically safe — the events so far down the probability tail that, if they come about, no-one will think to blame the person drafting for unwanted consequence. So, entire agreement clauses, no oral modification provisions, force majeure elaborations; doubt avoidance, and — as in the illustrated panel — a good hearty blizzard of nouns and adjectives to stand in for words like “legally”.

We shouldn’t laugh: this penumbra of practically but not theoretical safety vouches safe an entire industry of AI-powered NDA reading legaltech offerings. And where would be without them?

Don’t answer that.