Credit Suisse: Difference between revisions

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

For some years it has been an immutable rule of the market that if an unfortunate, weird, dumb, or preposterous thing happens in the market, Credit Suisse is sure to be involved and, if it hasn’t actually ''caused'' it, will be on the wrong ''end'' of it. This is the role that Deutsche Bank used to play. | For some years it has been an immutable rule of the market that if an unfortunate, weird, dumb, or preposterous thing happens in the market, Credit Suisse is sure to be involved and, if it hasn’t actually ''caused'' it, will be on the wrong ''end'' of it. This is the role that Deutsche Bank used to play. | ||

After a period of seven or more years in which Credit Suisse seemingly was drawn | Ironically — though, possibly ''causatively'' — Credit Suisse escaped the [[Global Financial Crisis]] comparatively unscathed. While its peers and competitors were being bailed out, nationalised, eviscerated, stress tested, analysed, supervised, inspected generally groped with great snapping of regulatory rubber gloves on parts of the institution they didn’t know ''could'' be groped, Credit Suisse got a pass, sat pretty and thumbed its nose at all the hubris. | ||

It may now wish it had got the rubber glove treatment while the going was good. For its peers seem — and look, its ''always'' to early to say this sort of thing, but for now, they seem — to have learned lessons about how banks should behave that Credit Suisse apparently did not. | |||

After a period of seven or more years in which Credit Suisse seemingly was drawn, like a moth to a candle, to every financial catastrophe going — its spying on its own executives, Malachite, [[Archegos]], [[Greensill]], Evergrande, [[Covid-19]], [[1MDB]], [[tax]] evasion, lockdown breaches, serial [[KYC]] and [[money laundering]] breaches, Bulgarian drug trafficking, a $500 million insurance fraud on the Georgian prime minister, $850m Mozambique tuna bonds fraud, and diverse sanction breaches — things looked like they were reaching an end-game in 2023 following the failure of the [[Silicon Valley Bank]] and a sudden market-wide loss of confidence in the Swiss lender. The irony being that [[SVB]] was the first major financial scandal in a decade that old “Lucky” the one-eyed dog had nothing to to with whatsoever. | |||

When market confidence in the global banking sector sank, it sank even more for Credit Suisse, dropping 30% in a day on the Ides of March. When its cornerstone investor, the Saudi National Bank, baulked at a capital call, Credit Suisse was forced to beg for a public statement of confidence from the Swiss National Bank and, when that didn’t work, a CHF50bn liquidity facility. That was enough to end Credit Suisse’s prospects as a credible global banking institution. | When market confidence in the global banking sector sank, it sank even more for Credit Suisse, dropping 30% in a day on the Ides of March. When its cornerstone investor, the Saudi National Bank, baulked at a capital call, Credit Suisse was forced to beg for a public statement of confidence from the Swiss National Bank and, when that didn’t work, a CHF50bn liquidity facility. That was enough to end Credit Suisse’s prospects as a credible global banking institution. | ||

Revision as of 10:32, 17 March 2023

|

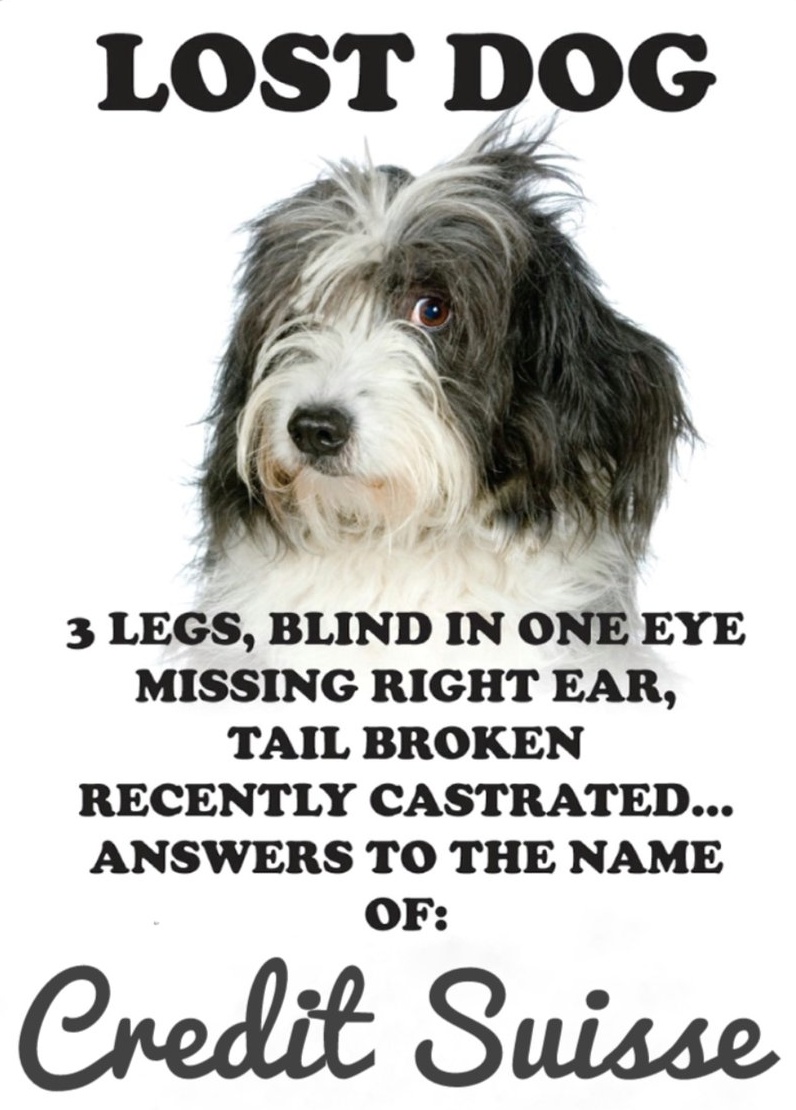

The proverbial missing dog of modern international finance. Also known amongst banking analysts as “Debit Suisse”.

For some years it has been an immutable rule of the market that if an unfortunate, weird, dumb, or preposterous thing happens in the market, Credit Suisse is sure to be involved and, if it hasn’t actually caused it, will be on the wrong end of it. This is the role that Deutsche Bank used to play.

Ironically — though, possibly causatively — Credit Suisse escaped the Global Financial Crisis comparatively unscathed. While its peers and competitors were being bailed out, nationalised, eviscerated, stress tested, analysed, supervised, inspected generally groped with great snapping of regulatory rubber gloves on parts of the institution they didn’t know could be groped, Credit Suisse got a pass, sat pretty and thumbed its nose at all the hubris.

It may now wish it had got the rubber glove treatment while the going was good. For its peers seem — and look, its always to early to say this sort of thing, but for now, they seem — to have learned lessons about how banks should behave that Credit Suisse apparently did not.

After a period of seven or more years in which Credit Suisse seemingly was drawn, like a moth to a candle, to every financial catastrophe going — its spying on its own executives, Malachite, Archegos, Greensill, Evergrande, Covid-19, 1MDB, tax evasion, lockdown breaches, serial KYC and money laundering breaches, Bulgarian drug trafficking, a $500 million insurance fraud on the Georgian prime minister, $850m Mozambique tuna bonds fraud, and diverse sanction breaches — things looked like they were reaching an end-game in 2023 following the failure of the Silicon Valley Bank and a sudden market-wide loss of confidence in the Swiss lender. The irony being that SVB was the first major financial scandal in a decade that old “Lucky” the one-eyed dog had nothing to to with whatsoever.

When market confidence in the global banking sector sank, it sank even more for Credit Suisse, dropping 30% in a day on the Ides of March. When its cornerstone investor, the Saudi National Bank, baulked at a capital call, Credit Suisse was forced to beg for a public statement of confidence from the Swiss National Bank and, when that didn’t work, a CHF50bn liquidity facility. That was enough to end Credit Suisse’s prospects as a credible global banking institution.

The consensus remains that, while the bank isn’t dead as such, it is only not dead thanks to the iron lung it is presently strapped to, so we might as well wind it down now, since it ain’t coming back.

Who would want it? Good question.