Tier 1 capital: Difference between revisions

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) No edit summary Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) No edit summary Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| Line 70: | Line 70: | ||

And we should not feel undue sympathy for distressed — ahem vultures — looking to buy a 7% fixed instrument for cents on the dollar when the issuer is in the midst of a well telegraphed existential meltdown? ''We should not''. Even if the ones who ''did'' read the prospectus. | And we should not feel undue sympathy for distressed — ahem vultures — looking to buy a 7% fixed instrument for cents on the dollar when the issuer is in the midst of a well telegraphed existential meltdown? ''We should not''. Even if the ones who ''did'' read the prospectus. | ||

One invests in common equity to take advantage of rapidly changing market conditions. An equity price is a capricious, will o’ the wisp sort of thing that flits about impishly, by driven by the unpredictable humours of the market. One can, and many do do make a living trading short-term movements. | |||

In ordinary times, interest-bearing notes — when AT1s — are much less volatile than common equity. Their market value will not fluctuate much day by day. Their main attraction is their coupon yield. You only benefit from that over time. AT1s reward long-term investment. In ordinary times their return is a linear function of ''how long '' you are prepared to hold them, and therefore how long you fund the bank’s tier 1 capital. | |||

Itvis different in a bank distress scenario. Here AT1s are unusually vulnerable: this is the very contingency they are designed to protect ''the bank'' against. As the banks capital ratio approaches criticality, their performance more and more to resembles the equity. | |||

''Convertible'' AT1s which, in the worst case, will turn into common equity, will converge on the common equity exactly. | |||

''Write-Down'' AT1s will become even ''more'' volatile than common equity. They are, effectively, binary options: either they are triggered, in which case they are worth zero, or they are not, in which case they recover, will eventually be called at 100, and in the meantime will continue to pay fat slugs of interest. | |||

Indeed, this is exactly what we saw. | |||

Should we feel bad that speculators looking for a quick buck, who held the notes for a couple of days, got hosed? No. This is exactly the bet they were taking. | |||

Should we feel bad for buy and hold investors who held from issue and were written down to zero? No. They did much better than common equity holders over that period. | |||

The tier one capital layer is there to protect depositors and vouchsafe the stability of the wider financial system, whose collected interests are best served by the bank remaining a going concern. That they happen to share that interest with the banks ordinary shareholders is beside the point. The bonds reward long-term investors — those who read the terms and clocked that “Perpetual Tier 1 Contingent Write-Down Capital Notes” meant these were notes that could be written down in a time of capital stress — most likely had a bank to sell last week. | The tier one capital layer is there to protect depositors and vouchsafe the stability of the wider financial system, whose collected interests are best served by the bank remaining a going concern. That they happen to share that interest with the banks ordinary shareholders is beside the point. The bonds reward long-term investors — those who read the terms and clocked that “Perpetual Tier 1 Contingent Write-Down Capital Notes” meant these were notes that could be written down in a time of capital stress — most likely had a bank to sell last week. | ||

Revision as of 08:35, 24 March 2023

|

Regulatory Capital Anatomy™

The JC’s untutored thoughts on how bank capital works.

Here is what, NiGEL, our cheeky little GPT3 chatbot had to say when asked to explain:

|

Tier 1 capital

/tɪə wʌn ˈkæpɪtl/ (n.)

Of a regulated financial institution, the capital level below everything else that gives comfort to the bank’s creditors — in particular, its depositors — that their debts will be met and deposit withdrawals honoured.

If you are a regulated financial institution (a bank) — but only if you are one of those— you must “hold” a certain percentage of tier 1 capital, though a certain type of financial analysts get annoyed if you say “hold”, for the pedantic reason that tier 1 capital is a really just what is left of your assets after you deduct your liabilities, and isn’t something you “hold”, as such.

Less pedantic types feel that since you have to monitor it every day, and do something, like issuing more tier 1 capital securities, if it isn’t there, this isn’t really a distinction worth getting het up about.

What are tier 1 capital securities, then?

Tier 1 common equity

The classic tier 1 capital is the institution’s ordinary share capital. This is known, by the same people who know coronavirus as “COVID-19”, as “tier 1 common equity”, or “CET1”.

Until 2008, that is all there really was Then the global financial crisis happened, and the world’s various bank regulator committees, councils and forums got together, promulgated largely coordinated set of bank resolution and recovery regimes, in the process savagely increasing tier one capital requirements with which banks had to comply.

Alternative tier 1 capital

When banks complained — equity capital is quite the drag on performance — the committees conceded there could be a layer of tuer 1 which wasn’t actually common equity, but could be made to behave like it if a bank’s chips ever got really down.

We suspect everyone thought that a large number of banks’ chips would not simultaneously get down again, so this was a largely academic issue — but it is March 2023 and here we all are. Again.

Anyway, this new layer of quasi common equity came to be known as “alternative” tier 1 capita, or “AT1” which, when said out loud, sounds like “eighty-one”.

AT1 capital takes the form of subordinated debt which the issuer may, but need not, call after a few years, As such, from an investor’s perspective, it is as theoretically perpetual as ordinary shares are.

In certain disaster scenarios it is also convertible into ordinary shares, at which point it becomes CET1, or may even be written off altogether. Conversions and write-downs are “contingent” on defined events, like capital thresholds being breached — der Teufel mag im Detail stecken to the max — so AT1s are also called “contingent convertible securities” or “co-cos”.

It became clear in March 2023 when Credit Suisse finally gave up the ghost, that many in the market, including AT1 investors, didn’t fabulously understand how they worked.

Debit Suisse and the irate bondholders

Famously, in that panicked Spring weekend in 2023 when it slipped into history[1] the “trinity” of Swiss regulators put a gun to UBS’s head, forced it to make an honest bank of Credit Suisse in a process in which it absorbed Lucky’s equity, and the jewels and hellish instruments of madness and torture secreted around its balance sheet — other than its AT1s. The regulators instead, by ordinance, directed Lucky to write down its to zero.

This — and there isn’t really a delicate way to put this, readers so let’s just come out with it — pissed the AT1 noteholders the hell off.

Their indignance was largely driven by foundational conceptions of what subordinated debt securities are meant to be — that is, senior to shareholders — rather than even a cursory glance at the terms or, goddammit, even the title of their Notes.

They were fortified in their dudgeon by other central bankers (BOE, ECB, the Fed) unhelpfully announcing, for the record, that that is not how they would expect to treat AT1s (you can just imagine FINMA honchos going “yeah, thanks Pal,” when a central banker from Greece — yes, yes, that Greece — went on record as saying “well needless to say we’d never do anything like that. We Greeks are civilised, not like the Swiss!”[2]) and now ambulance chasing litigators are whipping up even more foment, indelicately trawling LinkedIn to raise a pitchfork mob of aggrieved investors to go and sue — well, it isn’t clear who they would sue, or for what, since this was done by legislation — and even the normally mild-mannered financial analyst commentariat has been periodically erupting into virtual fist-fights about what the AT1s do or do not say.

Meanwhile, from the investors, lots of jilted lover energy: “How could I ever trust a central banker again?” sort of thing, and lots of “who knew Switzerland was a banana republic?” vibes, too.

Now the JC likes Switzerland, so he is staying right out of that debate: There are plenty of thought pieces from those more learned and temperate than the JC about that.

But still

But the conceptual question this all throws up, in the abstract, is an interesting one: should creditors, however subordinated, ever rank behind common shareholders? Surely not?

Everyone knew AT1s could get converted into equity, at which point they rank equally with shareholders, and even written off — but there seemed to be the expectation that a write-off would only happen if common shareholders are getting written off too.

First, a little spoiler: effectively ranking behind shareholders and actually ranking behind shareholders feel similar — especially if you have just been written down to zero while the shareholders live to see another day — but they are quite different things.

Two spoilers, in fact: issuers must have contemplated writing AT1s down while shareholders survived: otherwise, why even have a write-down option? A write-down contingent on total shareholder annihilation is no different from a normal conversion to equity: you get what the shareholders get: zero. That kind of write-down option would be meaningless.

The whole point of a write down to zero is to deliver a capital buffer and stave off an insolvency so the corporation can carry on. If it succeeds, the shareholders will live to see another day.

So the JC thinks those central banks who are on record as saying “we’d never write off AT1s before shareholders” are flat out wrong.

A corporation’s shareholders take all the profit and all the losses of the undertaking. You can only work out what those profit and losses are once every other claim on the enterprise has been settled. Those other claims have the feature of being debtor claims. Debtor claims all have defined payoffs; equity claims are, “whatever’s left”.

So, when resolving a company that has gone bust, you must deal with AT1 creditors before you finally settle up with shareholders. You can do this two ways: you can convert the AT1s into shares or, if its terms permit, you can just write them off altogether. Either way, by the time you deal with shareholders, no AT1s are left. Only shareholders remain.

Therefore, the AT1 investors do not actually rank behind shareholders. They can’t. They either become shareholders, or they are goneski. If they get converted into shares they may get some recovery, but only once all the company’s other creditors have been repaid in full. A written down AT1 has been paid in full. The liability was just zero.

But AT1 investors whose notes are written off still feel as if they are effectively ranking behind shareholders. This is because they get nothing and shareholders get something.

But is that really true?

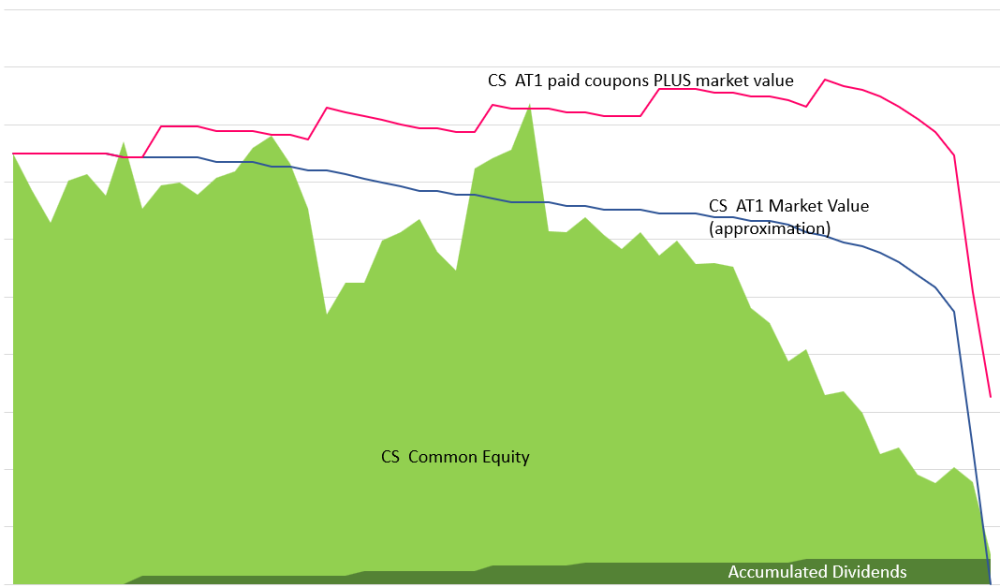

The panel above illustrates our best guess of the cumulative shareholder return — the diminishing cash dividends paid plus ongoing share price, which was in of course in insistent decline over 5 years — and cumulative AT1 return, which is a a much fatter, fixed coupon plus its market redemption value , which we have just made up, but on the premise that until things get truly dire, it will stay somewhere near par. It was trading at 25% on the last trading day before it was vapourised.

The obvious thing about this is that, for a buy and hold, long term investor, it's return has been better than the common equity, including after it was nixed. The combined coupons since issue are easily more than the final acquisition price. In all circumstances except a thermonuclear meltdown the Cocos were a vastly better investment.

“Ah yes, you counter, but tell that the the distressed investors who bought the AT1s on Saturday.

And we should not feel undue sympathy for distressed — ahem vultures — looking to buy a 7% fixed instrument for cents on the dollar when the issuer is in the midst of a well telegraphed existential meltdown? We should not. Even if the ones who did read the prospectus.

One invests in common equity to take advantage of rapidly changing market conditions. An equity price is a capricious, will o’ the wisp sort of thing that flits about impishly, by driven by the unpredictable humours of the market. One can, and many do do make a living trading short-term movements.

In ordinary times, interest-bearing notes — when AT1s — are much less volatile than common equity. Their market value will not fluctuate much day by day. Their main attraction is their coupon yield. You only benefit from that over time. AT1s reward long-term investment. In ordinary times their return is a linear function of how long you are prepared to hold them, and therefore how long you fund the bank’s tier 1 capital.

Itvis different in a bank distress scenario. Here AT1s are unusually vulnerable: this is the very contingency they are designed to protect the bank against. As the banks capital ratio approaches criticality, their performance more and more to resembles the equity.

Convertible AT1s which, in the worst case, will turn into common equity, will converge on the common equity exactly.

Write-Down AT1s will become even more volatile than common equity. They are, effectively, binary options: either they are triggered, in which case they are worth zero, or they are not, in which case they recover, will eventually be called at 100, and in the meantime will continue to pay fat slugs of interest.

Indeed, this is exactly what we saw.

Should we feel bad that speculators looking for a quick buck, who held the notes for a couple of days, got hosed? No. This is exactly the bet they were taking.

Should we feel bad for buy and hold investors who held from issue and were written down to zero? No. They did much better than common equity holders over that period.

The tier one capital layer is there to protect depositors and vouchsafe the stability of the wider financial system, whose collected interests are best served by the bank remaining a going concern. That they happen to share that interest with the banks ordinary shareholders is beside the point. The bonds reward long-term investors — those who read the terms and clocked that “Perpetual Tier 1 Contingent Write-Down Capital Notes” meant these were notes that could be written down in a time of capital stress — most likely had a bank to sell last week.

It sounds like there were plenty of buyers.

See also

References

- ↑ We have a sense Credit Suisse’s history is not done just yet but that, like Disaster Area frontman Hotblack Desiato, it is merely spending a year dead for tax (and, er regulatory capital) purposes. It may well be back, at least as a high-street banking brand in Switzerland.

- ↑ This is a paraphrase, and an exaggeration for effect, I freely admit.