Efficient market hypothesis

|

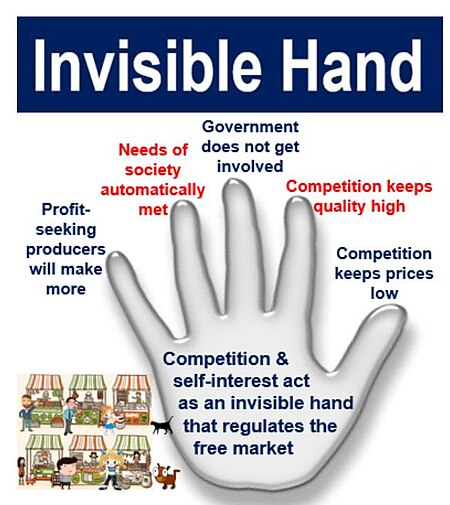

The efficient market hypothesis, first formulated by Eugene Fama, states (broadly) that an investor cannot systematically beat the market because all important information is already priced into current share prices. This owes something to Adam Smith’s invisible hand and the wisdom of the crowd: the infinite nudges and impulses of all investors in the market who, between them, necessarily have more information in aggregate than you do, nudge asset prices to the “correct” or “optimal” point, and anyone valuing an asset with with poor information will instantly be picked off by a better-informed arbitrageur.

Therefore, stocks already, always trade at the fairest value, meaning that anyone who does beat the market basically flukes it.

Statistical arbitrageurs, value investors like Warren Buffett and Edward Thorp, behavioural psychologists and, most recently, a bunch of day-traders on Reddit, have begged to differ. The gist of their arguments: “the market can stay irrational longer than you can stay solvent”

The JC has spotted a variation of EMH in the legal world, which he calls the efficient language hypothesis: the JC’s efficient language hypothesis states that the universally acknowledged advantages in efficiency, clarity, brevity and productivity offered by simple, clear and plain legal drafting are so compelling that sustained prolixity is impossible in commercial contracts, and all bilateral accords will eventually resolve themselves to, at most, terse bullet points rendered on a cocktail napkin, and ideally some kind of mark-up language or machine code. This, the JC goes on to conclude, must mean that the commercial world we appear to live in is just a bad dream.

Oddly, this seems to be taking longer to happen than anyone expected.