Contractual negligence

An attorney eyes you wistfully and slides a draft across the table to you. It states: "Party A shall not be liable for any losses, howsoever caused, unless they arise directly from its own negligence, fraud or willful default".

What is one to make of this? At a glance it seems perfectly reasonable. To be sure, it is time-honoured boilerplate, thrown into contracts to close them out like chump change tossed into the bill plate at the end of an agreeable meal. But it doesn't make a lot of sense. Let's do the easy ones first.

===Fraud===

You can't exclude contractual liability for fraud, so it's hardly a great concession to say so in a contract.

Wilful Default

A heartily-bandied phrase which sounds like it ought to mean something specific. The best guess of this fellow is it means a "deliberate refusal to perform one's obligations under a contract": not too far removed from fraud (it raises a presumption of fraudulence on the part of the actor in agreeing to the obligation in the first place) but in any weather a subset of the class of events called "breaches of contract".

Breaches of Ccontract, QED, entitle an innocent party to redress under the law of contract. So it ought cause your heart to leap to find a counterparty offering to be responsible for flagrant examples of this type of behaviour. Indeed; you might wonder why less wilful "defaults" aren't captured.

For here's the point, lazengem: The point of a contractual obligation is to have some means of enforcing its performance or achieving compensation for its non-performance. Is that what negligence is meant to do?

Negligence

Maybe. But negligence is a standard of behavior expected in tort, where, by definition, there is no contract between the parties that you can look to to see how they were meant to behave. Negligence is all good fun - reasonable men (and women), Clapham omnibuses, snails, ginger-beer, ferocious domestic animals, escaping water - but itall evolved ad hoc to address a particular human dilemma - the plight of an unseen neighbour - that simply doesn't exist where you have a contract. Here you know damn well who your neighbour is, having spent six months hammering out a legal agreement with the blighter. So it seems all rather forlorn that one should fall back, weakly, on a standard devised by imaginative judges to look after the interests of folk who had no contract addressing what should happen were they to be carelessly struck by a punt navigating the wrong way up a flooded avenue.

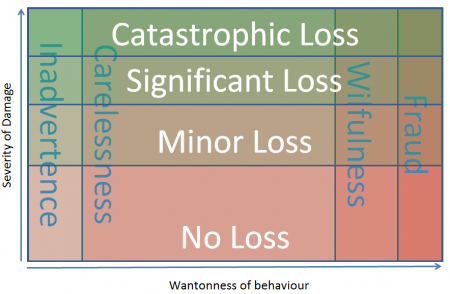

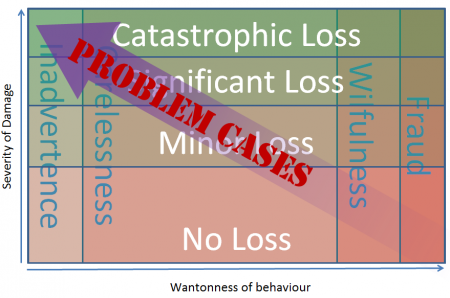

Consider the handsome table to the right. This charts all conceivable breaches of contract. The easiest cases are in the bottom right: not much loss, but the defaulting party has been utterly gratuitous in its behavior. Whatever the claim, it has no leg to stand on.

The hard cases are in the top left: here there has been little misbehaviour (but note our condition to entry: the strict terms of the contract have not been obeyed), but this has caused a significant loss. These, one fancies, are the ones this cute language excluding liability for negligence are meant to cover. But doing things this way betrays laziness or a lack of legal acuity from your counsel. It is not that you wish to apply an exclusion from contractual liability if a party hasn't been negligent - what you really mean to say is that you only have an obligation in the first place to exercise a certain standard of care. If you craft the contract that way, there's no need to carve out negligence, because you didn't breach the contract in the first place.

But isn't this an easier catch-all?

"But", yon lazy attorney wails, "adopting your approach means I have to write in a standard of care to every obligation under the contract. Surely it's easier to carve it out!"

But that is the point: The contract is meant to stipulate what you are expected to do. For some obligations, a "reasonable standard of care" rider is not appropriate. The payment of money, for example.

- Bill borrows Ben's car. He agrees to return it to Ben on Thursday at 3pm. At the appointed time Bill presents himself to Ben, but announces that he has just been mugged, and the car has been stolen. His mugger was quite unexpected, applied overwhelming force, and immediately drove the car into a wall and wrote it off. Through no fault of his own, Bill is unable to perform his obligation. Should he be able to rely on a carve out from liability because he has not been negligent?