Correlation

|

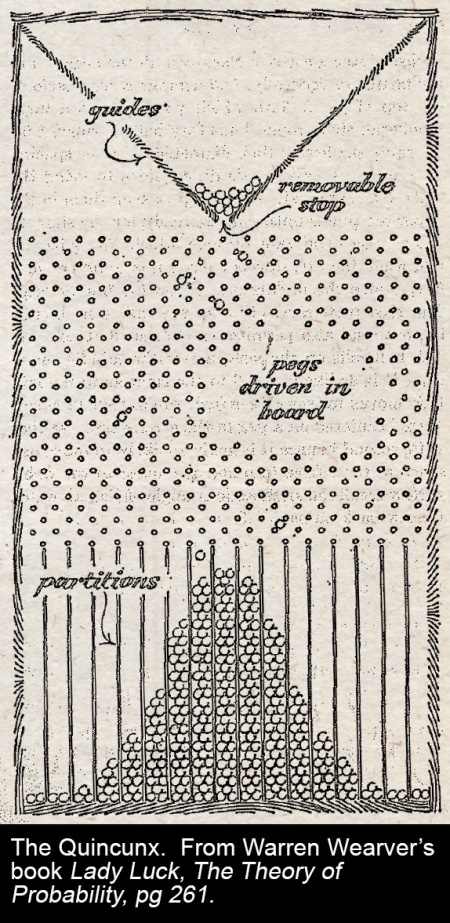

The idea, following from Sir Francis Galton’s experiments with a quincunx and first articulated by statistician Karl Pearson[1], that a relationship between two variables could be characterised according to its statistical strength and expressed in numbers, regardless of any perceived causal connection between them.

If one can derive significance from a purely statistical correlation, without any deeper mechanical theory of the universe that might tell us why, we are well on our way to an artificially intelligent future where robots can wipe elderly arses, all bankers are redundant, and it is only a matter of time before Skynet becomes self-aware and starts hunting down random skater kids from the 1990s.

Well, in some cases you can, in some cases you can’t,[2] but — irony upcoming — without a sophisticated theory of causality, it will be hard to tell them apart. That is to say, a bare correlation won’t tell you whether there is a causal arrow at all much less, if there is one, which way it flows.

“Correlation” is a synonym for ”coincidence”, though in its more fashionable usages among big data freaks this tends to be get somewhat, well, buried.

Correlation and causation

Now it is true that correlation doesn’t imply causation, but it doesn’t rule it out either. And it is certainly true that a lack of correlation does imply a lack of causation.

All other things being equal, a correlation is more likely to evidence a causation than a lack of correlation, right? This is one of those logical canards, as Monty Python put it, “universal affirmatives can only be partially converted: all of Alma Cogan is dead, but only some of the class of dead people are Alma Cogan.”

See also

References

- ↑ So Slate Magazine argues, at any rate.

- ↑ There are whole websites devoted to spurious correlations. Like, well, http://www.spuriouscorrelations.com.