How the laws of data science lie

|

The design of organisations and products

The Jolly Contrarian holds forth™

Resources and Navigation

|

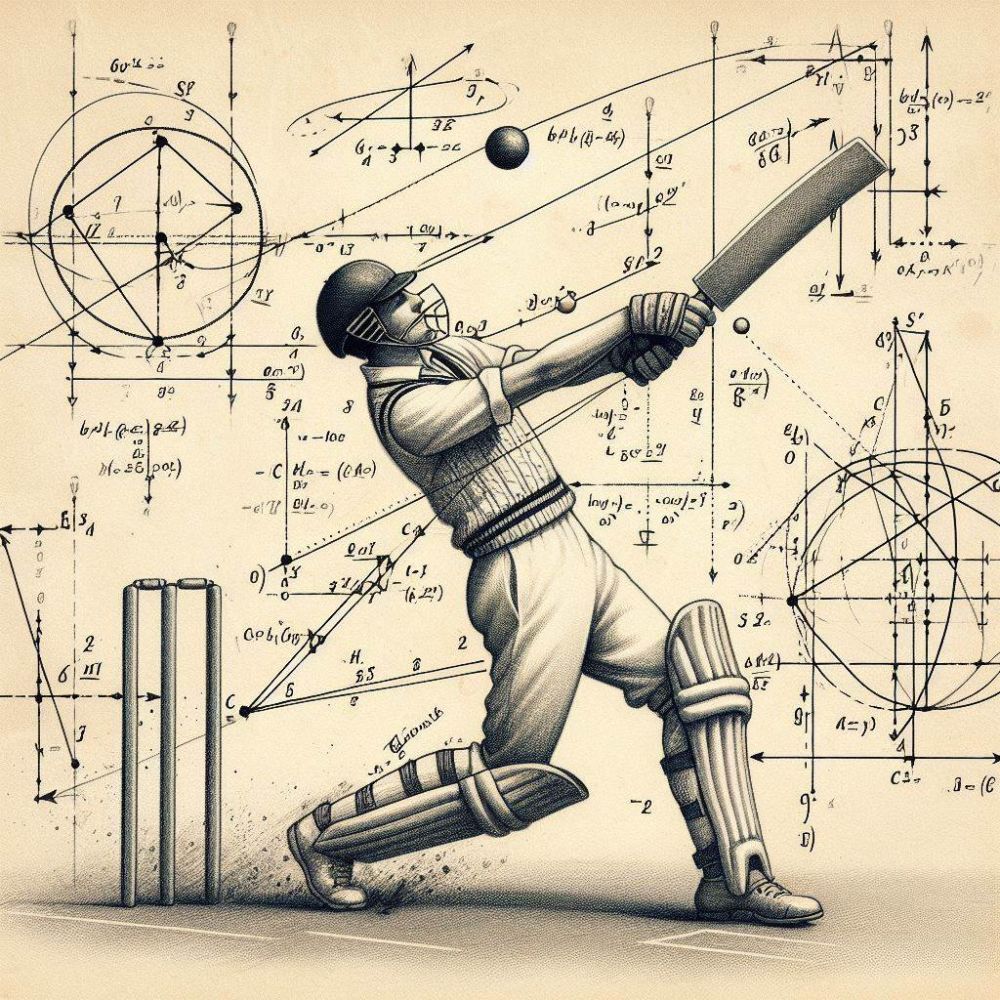

When a man throws a ball high in the air and catches it again, he behaves as if he had solved a set of differential equations in predicting the trajectory of the ball. He may neither know nor care what a differential equation is, but this does not affect his skill with the ball. At some subconscious level, something functionally equivalent to the mathematical calculations is going on.

- —Richard Dawkins, The Selfish Gene (1976).

Really powerful explanatory laws of the sort found in theoretical physics do not state the truth.

In 1983 philosopher Nancy Cartwright wrote the seemingly scandalous book How the Laws of Physics Lie. It is not quite the post-modernist screed it sounds but rather a serious and literate, but difficult, work of analytical philosophy. Cartwright’s argument is that the “conditions precedent” in which scientific laws can be expected work are so rigid, controlled and unlikely — in many cases impossible — that we never in fact experience “science” as it is supposed to happen.

For example, Newton’s second law of motion F=ma never applies directly to real-world situations without significant idealisation and approximation, ignoring a host of complicating factors such as friction, air resistance and inelasticity.

Scientific rules might be perfectly valid within their hypothetical conditions but as these conditions never prevail in practice, they are practically useless “in the real world”. We navigate the “lived regularities” of daily life somehow — that is what it means to be human — but not really with any help from science.

“We explain by ceteris paribus laws, by composition of causes, and by approximations that improve on what the fundamental laws dictate. In all of these cases the fundamental laws patently do not get the facts right.”

So, Newton’s laws of motion might us plot the theoretical trajectory of a moving projectile on a graph, they won’t help us catch a ball, let alone catch up with the proverbial crisp packet blowing across St Mark’s Square. You could spend a lot of time chasing around the piazza with a slide rule and an anemometer; you’ll end up going in, well, circles.

The same observation animates Gerd Gigerenzer’s preference for heuristics over science: despite Richard Dawkins’ trite conviction to the contrary, a fielder performs no differential equations on the way to catching a flying cricket ball.

“In order to pursue a prey or a mate, bats, birds, and fish do not compute trajectories in three-dimensional space, but simply maintain a constant optical angle between their target and themselves—a strategy called the gaze heuristic. In order to catch a fly ball, baseball outfielders and cricket players rely on the same kind of heuristics rather than trying to compute the ball’s trajectory.”[1]

We trick ourselves into believing the power of our scientific laws, wilfully blind to the ad hoc variations, adjustments and glosses that our messy world obliges us to impose upon them. We put down apparent disparities to the ineffable collection of intervening forces: we tell ourselves the laws of physics describe an idealised, Platonic model; our messy world is anything but, so we should expect variances from those pure predictions.

Now this is all well and good: we are simply “pragmatising” scientific laws: recasting them as rules of thumb and generalised guides to how the physical world will behave — they set outer bounds to our expectations but cannot give us real-time means of navigating the world. For example: the laws of physics tell us no cricket ball will attain escape velocity from a human bat-swing, however well struck; nor will it morph into a bowl of petunias as we try to catch it. But as for its precise trajectory through spacetime as I try to catch it — if science could ever yield an approximation of that, it would be far too late to be useful, and really we don’t have anything like enough data to run those calculations in any case.

So we must rely on our judgment, the facility for catching we have acquired through a lifetime of experience and practice, none of which involved solving differential equations: you cannot, as Nassim Taleb says, lecture birds on how to fly. Nor should we expect the mathematicians of Jesus College Cambridge, who have spent more time practising differential calculus than they have catching on the boundary at deep square leg, to be terribly good at cricket.[2] Science is a convenient post hoc explanation of what we did, not a guide to what we must do.

But the physical world is a complicated system: generally, a very, very complicated system, but insofar as the law of physics are concerned, not a complex one: we do not, by applying our models of physics to to the world, change how the world behaves. It is still, in a sense, linear: it is just our rules are approximations, not predictions. So the “lie” perpetrated by the laws of physics is broadly benign.

The JC’s sense is a similar thing may be true of data science, only it is less benign.

We tell ourselves that data models can predict our behaviour, are unfailingly accurate, that we should yield to their greater power. We no longer need “thick” human rules of moral principle to moderate our behaviour, because machines can systematically apply infinitesimally thin rules that equably adjudicate on any given particular.

This is all the more concerning with the advent of neural networks and large language models that we readily confess we do not understand at all, but we were already there, in our collective obeisance to, for example, the truth of DNA testing, forensic odontology, GPS navigation, or automated self-triage. It seems plausible; it looks devilishly technical; we have no good grounds to challenge it, so we defer to it.

We suppose spitting in a tube can tell us with certainty that we are 99.4% Scottish, 0.2% Bavarian with a smudge around Scandinavia, less than 4% Neanderthal, but the tests pick up no African heritage at all — despite the fact that every human on the planet is, ultimately, 100% African by origin (homo sapiens diverged from homo neanderthalensis hundreds of thousands of years before any human departed Africa).

These thin rules lie: they give us comfort in the truth of the things they opine about, the same way science does.[3] So there aren’t really 590 calories in that burger — it seems plausible if it is printed on the menu card, but the more permanently it is printed the less likely it is to be true. There are not really 49.57km in those directions to the airport; DNA tests don’t really know whether you are partly Bulgarian; ten thousand steps won’t transform your health; ten thousand hours won’t make you a concert violinist; two litres of water won’t ward off dehydration, one cannot match bite marks on skin with any reliability, let alone the certainty forensic dentists have been known to claim — but we of the laity are none the wiser, so such claims get made every day, and pass without challenge. It’s not independently testable. How would you know? Your implicit trust in untestable propositions begets trust in readings from instruments, and from nowhere the data modernists have bootstrapped themselves into a kind of credibility.

DNA testing for heritage is manifestly bullshit when you think about it. Where does your heritage start and stop? From the JC’s case 23andme confidently advised that my genetic heritage is almost exclusively from northwest England. Yet plainly this cannot be right; human beings have only inhabited northwest England for a couple thousand years, so so JC’s ancestors can’t have all started there — there must have been some influx from the Norman's, the goths, the Saxons, and the Vikings? — and at the other end of the JC family tree — what little we know of it involves New Zealand, Lincolnshire and Scotland and no-one really from Manchester at all.

Now if we go back in time 1000 years, being AI confidently advises this is approximately 30 generations, and any individual would have in the order of 1 billion direct

Forensic Odontology

Munchausen's by proxy

The hare test for psychopathy

Autism

Schizophrenia

See also

Template:M sa design how the laws of data science lie

References

- ↑ Gerd Gigerenzer, Simply Rational: Decision Making in the Real World (2015).

- ↑ JC recently had the opportunity to test this hypothesis. Jesus has a beautiful ground on a wonderful campus. They weren’t terribly good, but easily good enough to stuff JC’s team of North aging London dilettantes, and one sprightly reader in earth sciences caught JC out on the fence, albeit after four attempts and apparently by accident.

- ↑ Nancy Cartwright, The Laws of Physics Lie.