Agent lender

|

Banking basics

A recap of a few things you’d think financial professionals ought to know

|

Agent lender

/ˈeɪʤᵊnt ˈlɛndə/ (n.)

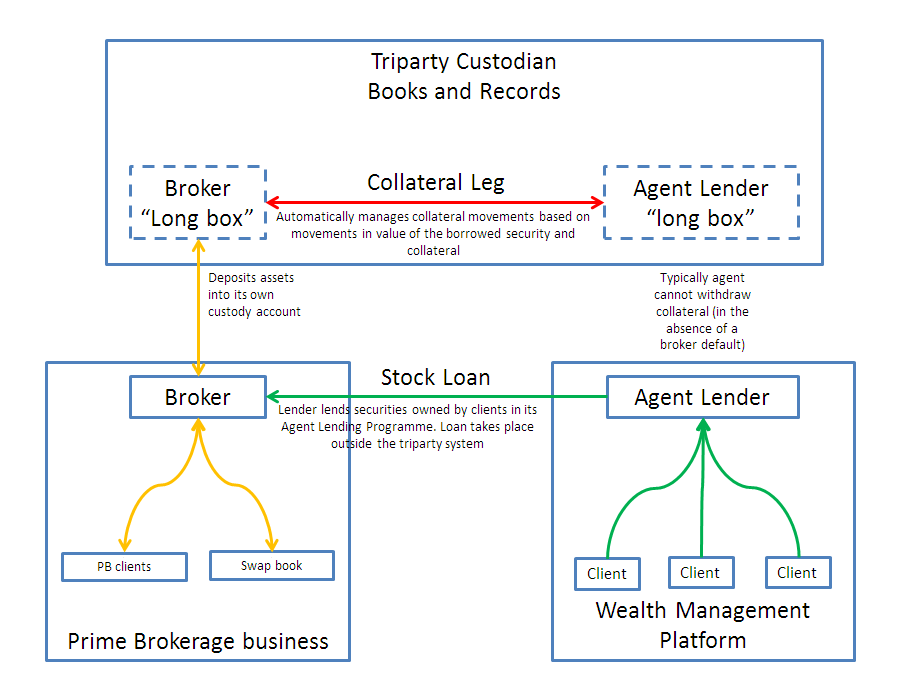

A financial institution with a significant wealth management or asset management business) who lends out its principals’ securities in the securities financing market.

And here, in this unfashionable back-alley of the capital markets, knee-deep in the clanking plumbing of the financial system, we find an utterly fundamental activity on which the whole edifice of the modern capital economy depends. Agent lending greases the wheels: it is the purest form of capital optimisation, a process that runs through every facet of modern finance.

How does it work? Simple in its element: you bring together two constituencies: on one hand, financial institutions with access to long-term investors in high-quality liquid credit assets who aren’t planning on doing anything with those investments and wish to earn a little more risk-free yield, and on the other, institutions needing high-quality liquid credit assets for their treasury and collateral operations in the short run, who will give them back later, and who can over-collateralise borrowings in the meantime with lower credit-quality assets knocking about in their trading businesses.

The former constituency: wealth managers and asset managers.

The latter constituency: investment banks.

Cash as anti-asset

We know that cash never sleeps: it must move, lest it waste away. As we have argued elsewhere, it is not capital but anti-capital: securitised evidence of indebtedness. Cash in hand is a token of the value you gave away: you were given it in lieu of value. Cash is a universal IOU, presentable to any creditor.

As long as you hold cash, you do not earn a return on the goods you gave away. Sand ebbs from the hourglass; the costs of existence continue to accrue. To hold cash is to be in a losing trade: we must give it away, in return for productive capital, and so we give someone else the problem of what to do with it. Cash is a hot potato. We pass it on as quickly as we can.

Contrast cash with a financial asset: a share, bond, certificate or deposit.[1] A financial interest offers the promise of a return: dividends, interest, income, and capital appreciation.

Transferable capital

But through the wizardry of seventeenth-century financial engineering, we have rendered capital assets as transferable instruments. We have separated economic capital investment from legal control and ownership. This has given rise to a whole class of derivative contracts — futures, options, forwards, synthetic swaps — and it means a capital investment is no longer a dead weight. Having exchanged its cash for a financial asset, and thereby having engaged its capital in the market, a “long” investor can generate a second return using derivative contracts in the marketplace.

A “long” investor — someone who buys and holds financial instruments — must find a regulated custodian with access to the market infrastructure to hold those assets on its behalf. This business costs: custody regulation is intrusive, and there is invariably a chain of intermediaries — sub-custodians, clearinghouses, securities depositories — all taking a fee, so there is a running cost to just owning capital assets.

And while they should, all going well, earn a good return, simple possession of those assets has a value in the market. People will pay good money to borrow them, that is to say, against a promise to return them later. A long investor can “reuse” its investments to generate an additional return.

|

Premium content

Here the free bit runs out. Subscribers click 👉 here. New readers sign up 👉 here and, for ½ a weekly 🍺 go full ninja about all these juicy topics👇

|

See also

References

- ↑ It should go without saying, but let’s say it: a cash deposit at a bank, in the depositor’s books, is not cash: it is a loan: a contract for the later repayment of cash.