Comfortable

|

Office anthropology™

|

Comfort

ˈkʌmfət (n.)

1. (Outhouse): A state of nonchalance towards a contingency that will never happen that an agent may reach upon payment of a suitable fee.

2. (Inhouse): Reluctant acquiescence, by means of a tacit acknowledgment that your immovable object really doesn’t have a prayer against the other guy’s irresistible force.

The beauty, for an agent, of the raging war between form and substance is the invitation it provides to stand on ceremony.

So, we implement process A, to deal with malign contingency X, but processes being only simplified models — derivatives — of the worlds they represent,[1] process A’s shadow will inevitably fall across benign contingencies Y and Z: circumstances not needing any process, but which “it won’t hurt” to subject to Process A anyway.

(The alternative would be a Process A', drawn wholly inside the boundary of contingency X, and whose shadow therefore didn’t fall across any benign contingencies, but which also did not quite cover all instances of malign contingency X. A process like this, which fails to address tail risks, is a bad process).

We should expect process A to get in the way every now and then, when a contingency Y or Z comes about. The options are (i) to run process A anyway, even though everyone knows it isn’t needed, or (ii) to waive process A, invoking process B (the “process A waiver process”). Either option has a cost: option (i) being marginally preferable because it is already costed in. Justifying option (ii) involves demonstrating the cost of obtaining the waiver will be less than the cost of running process B and so will result in a saving. This will trigger process C (the “justifying the cost of new business initiatives process”) which will, of course, increase the cost of process B, and make process B more likely to fail.

There is another way of doing things, of course: a subject matter expert — which we define as “one who understands the territory and therefore the map’s limitations” — can apprehend that it is contingency Y, make the substantive judgment that, while formally applicable, Process A is not relevant, and thereby ignore process A.

This will upset two categories of people: administrators — that class of people who are not subject matter experts, therefore don't understand the territory, fetishise the map, and suffer whenever the map is diregarded and (ii) those who stand to be gain by rigid application of the map, many of whom will be the same people.

This leads the JC to offer two models of operation

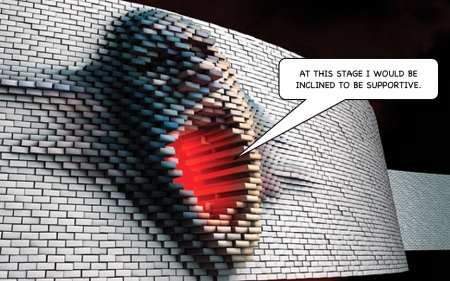

Usually expressed in the subjunctive: You could get comfortable by being inclined to be supportive at this point in time — proverbial broomsticks propping up any number of escape hatches, barn doors, and manholes through which you could scarper, bolt or drop, were the circumstances to recommend it — there goes that subjunctive again — but through which you know you won’t have to, because should this whole thing turn to mud, so many other people will be put in the stockade before you that those lovely portals — still propped up by your trusty broomsticks, if you’ve played it right — will give your sorry behind all the shelter it should need from the forthcoming The tempest.

So — get comfortable in there.

See also

- ↑ We take it as axiomatic that, the “real world” being analogue, fractal and complex, a process cannot perfectly map to a target contingency: to believe it might is to mistake a map for the territory.