No One Would Listen: A True Financial Thriller: Difference between revisions

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| (10 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

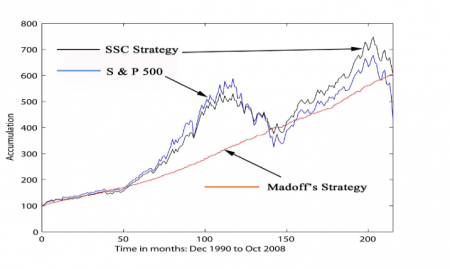

{{review|No One Would Listen: A True Financial Thriller|Harry Markopolos | {{a|book review|[[File:Madoff performance.png|450px|thumb|center|A [[Ponzi scheme]], yesterday]]}}{{br|No One Would Listen: A True Financial Thriller}}<br> | ||

{{author|Harry Markopolos}} | |||

===Greek Tragedy=== | |||

Cassandra was a beautiful Trojan princess who Apollo blessed with powers of clairvoyance but, when she rebuffed him, he cursed her by ensuring no-one would believe anything she said. Thus, her admonitions about the fall of Troy (it may have been she who warned “beware of Greeks bearing gifts”) fell on deaf ears and, as Wikipedia beautifully puts it, her “combination of deep understanding and powerlessness exemplify the tragic condition of humankind". | Cassandra was a beautiful Trojan princess who Apollo blessed with powers of clairvoyance but, when she rebuffed him, he cursed her by ensuring no-one would believe anything she said. Thus, her admonitions about the fall of Troy (it may have been she who warned “beware of Greeks bearing gifts”) fell on deaf ears and, as Wikipedia beautifully puts it, her “combination of deep understanding and powerlessness exemplify the tragic condition of humankind". | ||

I dare say {{author|Harry Markopolos}}, who repeatedly alerted authorities to [[Bernie Madoff]]’s [[Ponzi scheme]] for almost a decade before it finally fire-balled, knows how Cassandra felt. This is his recounting of his whole grisly story. | I dare say {{author|Harry Markopolos}}, who repeatedly alerted authorities to [[Bernie Madoff]]’s [[Ponzi scheme]] for almost a decade before it finally fire-balled, knows how Cassandra felt. This is his recounting of his whole grisly story. | ||

At that level, this is a fascinating account of a genuinely Greek tragedy — irony intended — which contains exactly the elements of Cassandra's tale (except, perhaps, the unbearable beauty). {{author|Harry Markopolos}} was possessed not just of the vague discomforts that a know-it-all-after-the-event windbag might use to claim fore-knowledge: to the contrary, he identified, in gruesome and glaring detail, that [[Bernie Madoff]] was running a [[Ponzi scheme]], precisely why, precisely how, and offered some precise and simple measures by which an investigating authority could cheaply verify his allegations (such as “ask to see his transaction | At that level, this is a fascinating account of a genuinely Greek tragedy — irony intended — which contains exactly the elements of Cassandra's tale (except, perhaps, the unbearable beauty). {{author|Harry Markopolos}} was possessed not just of the vague discomforts that a know-it-all-after-the-event windbag might use to claim fore-knowledge: to the contrary, he identified, in gruesome and glaring detail, that [[Bernie Madoff]] was running a [[Ponzi scheme]], precisely why, precisely how, and offered some precise and simple measures by which an investigating authority could cheaply verify his allegations (such as “ask to see his transaction confirmations”!) This he sent, in writing,<ref>[[index.php?title=Media:Markopolos.pdf|Harry Markopolos’ 18 page submission to the SEC]]</ref> to the [[Securities and Exchange Commission]] about five times over the course of a decade. | ||

But the fact that the [[SEC]] was under-staffed, under-skilled or over-populated with financially illiterate lawyers, comes ''nowhere close'' to explaining why Markopolos was systematically ignored. If you read Markopolos’ submission to the SEC from 2005 — see the footnotes below — you will see that one didn’t need to be an expert on option split-strike conversion strategies to realise something must have been dreadfully wrong with Madoff’s operation. | |||

Anomalies, as depicted in scientific literature, are fleeting imbalances; momentary disruptions in the established order which dissipate so quickly as to not be reliably measurable, and thus do not falsify existing orthodoxy. We dismiss anomalies with platitudes such as “stuff happens” or “this is the exception that proves the rule". | Anomalies, as depicted in scientific literature, are fleeting imbalances; momentary disruptions in the established order which dissipate so quickly as to not be reliably measurable, and thus do not falsify existing orthodoxy. We dismiss anomalies with platitudes such as “stuff happens” or “this is the exception that proves the rule". | ||

A fifteen-year, 50 billion dollar fraud | A fifteen-year, 50 billion dollar fraud is not an “anomaly”. It simply isn’t credible to put this down to an unfortunate confluence of improbable human errors. | ||

The collective failure to see [[Bernie Madoff]] for what he was feels like a symptom of a much more fundamental malaise. That feeling is augmented by other recent “anomalies”: Nick Leeson; [[LTCM|Long Term Capital Management]]; [[Enron]]; Amaranth; the Dot-Com bust; Jerome Kerviel; [[Lehman]]; AIG. Each of these “anomalies” went on, in plain sight, for years. | The collective failure to see [[Bernie Madoff]] for what he was, feels like a symptom of a much more fundamental malaise. That feeling is augmented by other recent “anomalies”: Nick Leeson; [[LTCM|Long Term Capital Management]]; [[Enron]]; Amaranth; the Dot-Com bust; Jerome Kerviel; [[Lehman]]; AIG; Theranos; WeWork; Wirecard; Archegos; Greensill. Each of these “anomalies” went on, in plain sight, for ''years''. | ||

Are these really anomalies? That, in the vernacular, is the elephant in the room. | Are these really anomalies? That, in the vernacular, is the elephant in the room. | ||

In focusing on the minutiae of the Madoff investigation | In focusing on the minutiae of the Madoff investigation — and you can’t really blame Harry Markopolos for doing that; it’s what he knows — Markopolos doesn’t ask that question: what ''is'' it, structurally, systemically, even ''sociologically'' about our financial system that can allow these “anomalies” to persist? That they can recur suggests a [[paradigm]] in crisis; that something about our assumptions and parameters; about [[Risk taxonomy|the way we collectively look at the financial risk]], is fundamentally misconceived. | ||

I thought, when I first wrote this review, that the book that identifies that error is yet to be written. It turns out it ''has'' been written, just no-one pays it any attention. It is Charles Perrow’s ''Normal Accidents'', and he wrote it in 1984. | |||

{{sa}} | {{sa}} | ||

| Line 31: | Line 26: | ||

*[[Risk taxonomy]] | *[[Risk taxonomy]] | ||

{{ref}} | {{ref}} | ||

{{newsletter|5/2/2021}} | |||

Latest revision as of 18:45, 14 April 2021

A Ponzi scheme, yesterday

|

No One Would Listen: A True Financial Thriller

Harry Markopolos

Greek Tragedy

Cassandra was a beautiful Trojan princess who Apollo blessed with powers of clairvoyance but, when she rebuffed him, he cursed her by ensuring no-one would believe anything she said. Thus, her admonitions about the fall of Troy (it may have been she who warned “beware of Greeks bearing gifts”) fell on deaf ears and, as Wikipedia beautifully puts it, her “combination of deep understanding and powerlessness exemplify the tragic condition of humankind".

I dare say Harry Markopolos, who repeatedly alerted authorities to Bernie Madoff’s Ponzi scheme for almost a decade before it finally fire-balled, knows how Cassandra felt. This is his recounting of his whole grisly story.

At that level, this is a fascinating account of a genuinely Greek tragedy — irony intended — which contains exactly the elements of Cassandra's tale (except, perhaps, the unbearable beauty). Harry Markopolos was possessed not just of the vague discomforts that a know-it-all-after-the-event windbag might use to claim fore-knowledge: to the contrary, he identified, in gruesome and glaring detail, that Bernie Madoff was running a Ponzi scheme, precisely why, precisely how, and offered some precise and simple measures by which an investigating authority could cheaply verify his allegations (such as “ask to see his transaction confirmations”!) This he sent, in writing,[1] to the Securities and Exchange Commission about five times over the course of a decade.

But the fact that the SEC was under-staffed, under-skilled or over-populated with financially illiterate lawyers, comes nowhere close to explaining why Markopolos was systematically ignored. If you read Markopolos’ submission to the SEC from 2005 — see the footnotes below — you will see that one didn’t need to be an expert on option split-strike conversion strategies to realise something must have been dreadfully wrong with Madoff’s operation.

Anomalies, as depicted in scientific literature, are fleeting imbalances; momentary disruptions in the established order which dissipate so quickly as to not be reliably measurable, and thus do not falsify existing orthodoxy. We dismiss anomalies with platitudes such as “stuff happens” or “this is the exception that proves the rule".

A fifteen-year, 50 billion dollar fraud is not an “anomaly”. It simply isn’t credible to put this down to an unfortunate confluence of improbable human errors.

The collective failure to see Bernie Madoff for what he was, feels like a symptom of a much more fundamental malaise. That feeling is augmented by other recent “anomalies”: Nick Leeson; Long Term Capital Management; Enron; Amaranth; the Dot-Com bust; Jerome Kerviel; Lehman; AIG; Theranos; WeWork; Wirecard; Archegos; Greensill. Each of these “anomalies” went on, in plain sight, for years.

Are these really anomalies? That, in the vernacular, is the elephant in the room.

In focusing on the minutiae of the Madoff investigation — and you can’t really blame Harry Markopolos for doing that; it’s what he knows — Markopolos doesn’t ask that question: what is it, structurally, systemically, even sociologically about our financial system that can allow these “anomalies” to persist? That they can recur suggests a paradigm in crisis; that something about our assumptions and parameters; about the way we collectively look at the financial risk, is fundamentally misconceived.

I thought, when I first wrote this review, that the book that identifies that error is yet to be written. It turns out it has been written, just no-one pays it any attention. It is Charles Perrow’s Normal Accidents, and he wrote it in 1984.